The ballad of the Kangaroo Bandit

In this extract from ‘Haramacy’ — an essay collection exploring visibility, invisibility, and race — writer Joe Zadeh reflects on mixed-race identity, growing up in northern England, and the seemingly invisible bank robber ‘the Kangaroo Bandit’

By Joe Zadeh

From the summer of 1999, southern California was plagued by one of the most prolific bank robbers in American history. The man worked alone and moved strategically from city to city, bank to bank. By March of 2001, the FBI suspected he’d hit 24 banks in 19 months. Sometimes he robbed two or three in a week. The media dubbed him the ‘Kangaroo Bandit’ because he wore a backpack on his chest — but I think they should have called him the ‘Octopus’. He was declared the most wanted man in California, but nobody could catch the Kangaroo Bandit.

“It’s tempting to liken him to smoke,” reported the Los Angeles Times, at the height of his spree. “He coils in and out of view, his presence an omen of danger. Then he evaporates into a sunlit afternoon, while those left behind wonder what it is they have just seen.”

The FBI knew the Kangaroo Bandit was around 25–30 years old, around six feet tall and around 200 lbs. He usually wore long-sleeved shirts, dark sunglasses and a baseball cap. Sometimes he ran off; other times, he got into a red Toyota pickup or a black sports car. But the human behind those details, the gross physical facts of skin, hair and bone, remained a mystery. You see, the Kangaroo Bandit had a special power: nobody could decide how he looked.

Witnesses described him as everything from a dark-skinned white male to a light-skinned African American. Some said Puerto Rican. Others said Brazilian. A few swore he was Middle Eastern. And some of the bank tellers were convinced he was wearing dark mascara. “You know they all can’t be right,” said FBI Agent Joseph White. Photos and security camera footage didn’t help. Sometimes his skin looked fair, sometimes it looked dark. Sometimes he had a moustache, sometimes a beard, and sometimes he was completely clean-shaven. The Kangaroo Bandit was large, he contained multitudes.

The FBI asked the public for help, offering a $15,000 reward for anyone who could help find the robber. Hundreds of people called in, turning in innocent men of every skin colour imaginable. Race is one of the fundamental ways society categorises people, and yet something was short-circuiting. He wasn’t just moving between races, he was playing with them. The British-Jamaican sociologist Stuart Hall said that the body is a text, which we all inspect like literary critics — and yet nobody could read this man.

I am no bank robber, but I have been likened to smoke. I was born in Gateshead and I am a mixed-race male — a Brown father (Iranian) and a white mother (English). Most people visually identify me as white: an Englishman with a Geordie accent and a decent tan. The same way they would have identified Steve Jobs as white, despite the fact his birth father was a Syrian Muslim from Homs called Abdulfattah Al-Jandali. And yet, just like the Kangaroo Bandit, my skin seems to change all the time.

The first time I was racially abused I was called a “paki”. The second time I was called a “dirty Israeli”. A Scottish girl once called me a “fucking geranium”, but that was just funny. I’ve had white people tell me I’m Brown, white people tell me I’m white, Brown people tell me I’m white, and Brown people tell me I’m Brown. Iranians just tell me I’m not Iranian enough.

When I first went on a video call with the editors of this book, I irrationally convinced myself that they might see my face for the first time on camera and think, ‘Oh, you’re a lot whiter than we imagined. Sorry, we can’t include you!’

People aren’t what we wish them to be, nor what they seem to be. They are what they are. I am English. I am Iranian. I am geranium. I coil in and out of view. And while I may not evaporate into sunlit afternoons, my presence, especially in airports, is seen as an omen of danger.

Airports are the gladiatorial arena of race and ethnicity. Since the age of 25, I’ve been taken to one side for an extra bag check or additional questions at almost every one I’ve visited, even on the small Channel Island of Guernsey, with its one runway. Yes, it’s me, I have come to bomb the place where you make the Gold Top milk.

“My mixed-race experience has more often been one of inner conflict and confusion”

— Joe Zadeh

In 2019, I flew to New York. My bag was checked twice at security. Then, at the gates, I was taken to one side and put in a cordoned-off area with six other men; I was the only one who seemed visibly white. Two of them looked at me, perplexed. “Iranian,” I said, and they smiled and went back to their phones.

Our bags were opened and checked. I boarded the plane, sat down and put on my seatbelt. Then my name was called over the tannoy, with a few others. My bags were removed from the overhead compartments and checked one more time, in front of the entire plane carriage. It was brutal and embarrassing. Yet I can’t deny that somewhere deep inside me there was a strange sense of pride. At that moment I was more Iranian than ever.

Mixed-race people are often used to symbolise racial harmony, especially in advertising where brands are keen to appear forward-thinking and inclusive. But my mixed-race experience has more often been one of inner conflict and confusion. In a world riven by racial fault lines, it’s bewildering to exist in a rupture. To get by, you need to embrace contradiction, accept the mangle, and live in a state of cognitive dissonance, whereby the mind is always filled with conflicting thoughts and feelings. Split at the root. Racially ambiguous. Racially amphibious.

“I stand at the edge where Earth touches ocean,” wrote the American-Mexican writer and self-described “Chicana, tejana, working-class, dyke-feminist poet” Gloria E. Anzaldúa, “where the two overlap/a gentle coming together/at other times and places a violent clash.”

My English grandad was a lorry driver from a small village in Northumberland who fought for Churchill in World War Two, voted for Margaret Thatcher and always donated to “the Legion”. My Iranian grandad was a sugar maker from Tehran, and a card-carrying member of the communist party (known as the ‘Tudeh’ party). He despised Britain for the way it had invaded Iran in 1941, decimated his country and helped topple its democratic leaders during the 1953 Iranian coup d’état. My father often tells me, through humble laughter, that it’s good he never lived to meet his British grandchildren, because he would have been ashamed to know they existed. At school, my father was taught how the evil British businessman William Knox D’Arcy stole Iran’s oil, while my mother was taught how Britannia ruled the waves.

My English grandad was a good, kind man with big, bony hands and twinkling eyes, and the limited racial awareness quite typical of a small village in 1970s rural England. When my mother took my father to the village, Grandad took him to the local pub. The bar and lounge fell silent and nobody made eye contact. The village, at the time, had a population of around 1,500. Some, I’m told, had never seen a Brown man until my father walked in. Grandad told my mother, “He’s nice, but I don’t want you marrying a dark-skinned fella.”

My mother and father got married in 1983 anyway. Grandad and my father became good friends. They travelled to lorry shows together; shows where you look at lorries. They carried on going to the village pub, where Grandad would proudly announce him as “my son-in-law”.

When my mixed-race forearms go their brownest, they don’t remind me of my father, they remind me of Grandad. There was a certain milky paleness beneath my father’s Iranian skin, but Grandad’s English skin always turned a deep and musty olive after long afternoons tending the tomatoes in his greenhouse with his cream shirt sleeves rolled past the elbow. After a hot summer, his skin went slightly darker, even, than my Iranian father’s. And yet this metaphysical concept floated in the air between them, still through friendship. A subtle difference invisible to the naked eye. Grandad’s whiteness, my father’s darkness.

A researcher in the Pacific coral reef once recorded seeing an octopus change colour 177 times in a single hour. Yellow, red, brown, black, as well as glittering greens, blues, golds and pinks. Their colour can change with their mood, but more often than not an octopus is trying to convince either predators or prey that it is really something else.

I did this on a cold doorstep in Telford, Shropshire, last winter. I was canvassing for the Labour Party ahead of the 2019 UK general election, speaking to a woman in her late forties outside her home. We were discussing everything from education to austerity; then she unleashed a long rant on immigration.

“How can we be paying all those taxes, and working so hard,” she said, “and then we’re put in a queue for the NHS behind all these unemployed immigrants?”

She didn’t know I was the son of an immigrant. I imagine she assumed I would have been browner or blacker. She couldn’t see the glittering greens, blues, golds and pinks. I felt desperate to tell her, but another part of me just wanted to listen. Unaware of where I came from, she voiced her prejudices freely — not defiant, almost confessional. In that moment, I was granted a view beyond the ugly weeds of her racism to see the roots below.

Once we moved past the fictional hordes of immigrants clogging up the hospitals and raking in benefits, it was clear she was wracked with genuine fears around health and financial insecurity. Her husband, who was self-employed, had become ill and been forced to take six months off work, in pain and not earning. Hearing his name, he joined us at the door on crutches. Life was quite visibly shit. But in the desperate search for blame, they’d taken a wrong turn. They didn’t blame the government, who had just drastically downgraded their local hospital and closed the A&E. They missed the facts and found a scapegoat.

“Who’s that lady we like, the one who tells it like it is?” she said.

I took a few hopeful guesses.

“Katie Hopkins,” said her husband.

I realise that to some, to just stand and listen would have been inconceivable. My father would have found it inconceivable. But part of the white privilege I carry is that racism is not a part of my everyday life. It’s rare and quick, not everywhere and always. In a way, I felt white enough to entertain her. With my identity cloaked, I got a little look at the conditions in which her racism grew.

The Filipino-American clinical psychologist Maria P.P. Root has argued that mixed-race individuals can expand the discussion and potentially take us beyond race. After all, we have both feet in both groups. And in a world of maddening polarisation — in which people seem stuck in alternate realities, where each side has their own facts, histories, and narratives — I can see the powerful role of someone who has experienced both white privilege and racism. We’re like walking sociological experiments, wooden horses rolling through the gates of Troy.

“Your blood is probably as mixed as mine; I was just mixed recently ”

— Joe Zadeh

And yet, I couldn’t bring myself to say anything much at all to this woman and her husband. The moment was there and I just watched with wide eyes. ‘What do I say? How do I say it? And why me? Who do I think I am? Some sort of mixed race messiah?’ I made a few half-hearted points and shrugged at things I didn’t agree with, then fake-smiled a goodbye and walked away. In the shower, for weeks afterwards, I replayed the scenario in my head in a thousand different ways.

The village church wouldn’t allow my father, a Brown non-Christian, to be married there, so my parents did the ceremony at Newcastle Civic Centre and then, in a charming act of defiance, drove to the village church afterwards and took their photos outside. A passer-by who went to school with my mother walked over to congratulate her. When she pointed out my father as her husband, he sighed and said, “Could you not have found a nice English bloke?”

I used to think their interracial wedding photos seemed so radical and groundbreaking for 80s northern England. But then I did some reading and found out there were married interracial couples living in Newcastle as far back as the second century (like Regina of St Albans and Barates of Palmyra, now modern Syria, who lived together in North Shields, a small town on the north bank of the River Tyne). The Cambridge classicist Mary Beard cited them, and many other examples, in a debate sparked in 2017 when the alt-right conspiracy theorist Paul Joseph Watson wrote that a BBC programme depicting a mixed-race family in Ancient Britain was “the Left” trying to “rewrite history”.

When you know about Regina and Barates — and the racial mixing that has always under-pinned British history, from Chinese communities in 19th-century Liverpool to the Arab, West African and Caribbean communities of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay that predate the Windrush Generation of 1948 — it’s hard to swallow the various books, news stories and academic papers that come out every year beckoning the approaching future of “mixed-race Britain” — like this is a novel moment for civilisation. The growing population of “mixed-race” Britain would be better described as a growing population of people whose race has mixed in living memory. Even using the term ‘mixed-race’ sometimes feels, to me, like accepting the notion that racial purity does exist, somewhere out there.

How do we measure racial purity? Where are the boundaries of my whiteness and brownness?

If I have a child with a fellow mixed-race person, are they mixed-race? If I have a child with a white person, will they be half mixed-race? Or will they just be white? Where is the cut-off point? Where does the ocean touch the Earth? And who decides this? When will my mixedness be flushed out of the system? Can you be a third-generation immigrant? Fourth? How much of your racial identity is what you are and how much of it is what people see in you?

When we talk about our genealogy, why do we only go back so far? Genetic testing has repeatedly shown that Europe is a melting pot of bloodlines from Africa, the Middle East and the Russian steppe. The geneticist Adam Rutherford estimated that over 500 years, each of us has around 1,048,576 ancestors. Inside us all bubble ancient cocktails that have been shaken since the very beginning. Your blood is probably as mixed as mine; I was just mixed recently.

Sometimes, I like to watch YouTube ‘reaction videos’ of people doing 23andMe tests and discovering that they are 15 per cent African, or 10 per cent Native American, or 5 per cent Jewish, or all three. And yet there is something in their voices that makes me think they just can’t comprehend it. “Either we are all multiracial, or, really, none of us are,” said the Filipino-American philosopher Ronald Sundstrom. Or, as Andy Warhol — the late Slovak-American artist and son of two working-class Lemko emigrants, a distinct minority ethnic group from the Lemkivshchyna region of Eastern Europe — quite decadently put it, “If everybody’s not a beauty, then nobody is.”

The FBI never caught the Kangaroo Bandit. After he’d robbed over one hundred banks, he simply handed himself in, having come to the conclusion that his crimes were not as “victimless” as he first thought. And when he was finally identified and imprisoned, the trick of his baffling invisibility was revealed. The Kangaroo Bandit was neither Black, white, Puerto Rican, Brazilian nor Middle Eastern. You already know why. A Black father and a white mother had created a man who looked like almost everything in between.

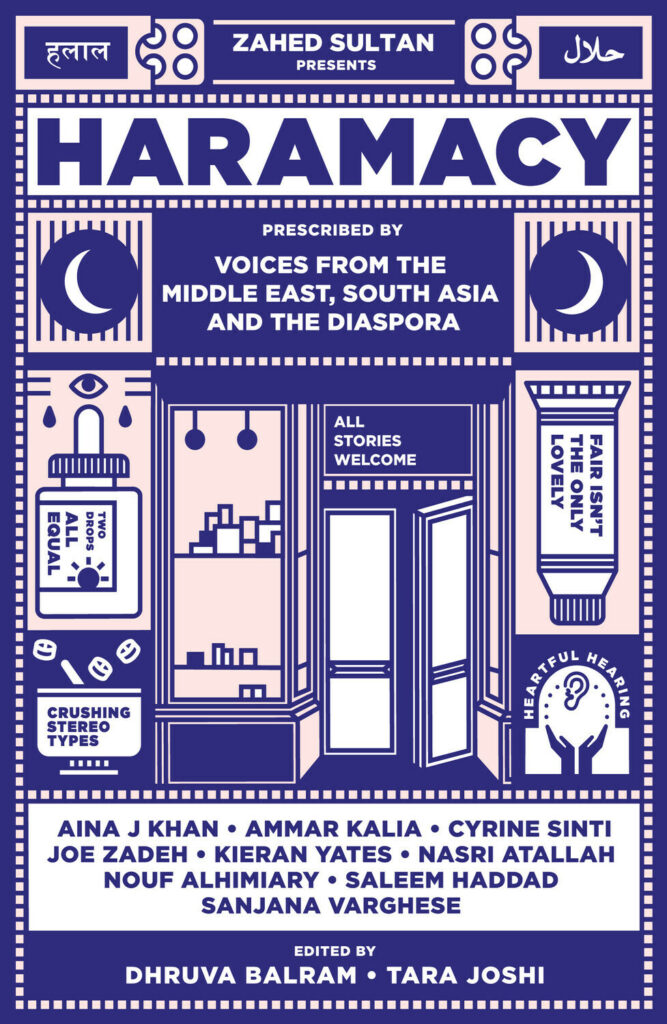

Haramacy, edited by Dhruva Balram and Tara Joshi, is out now from Unbound books.

Taken from the August/September 2022 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it here.