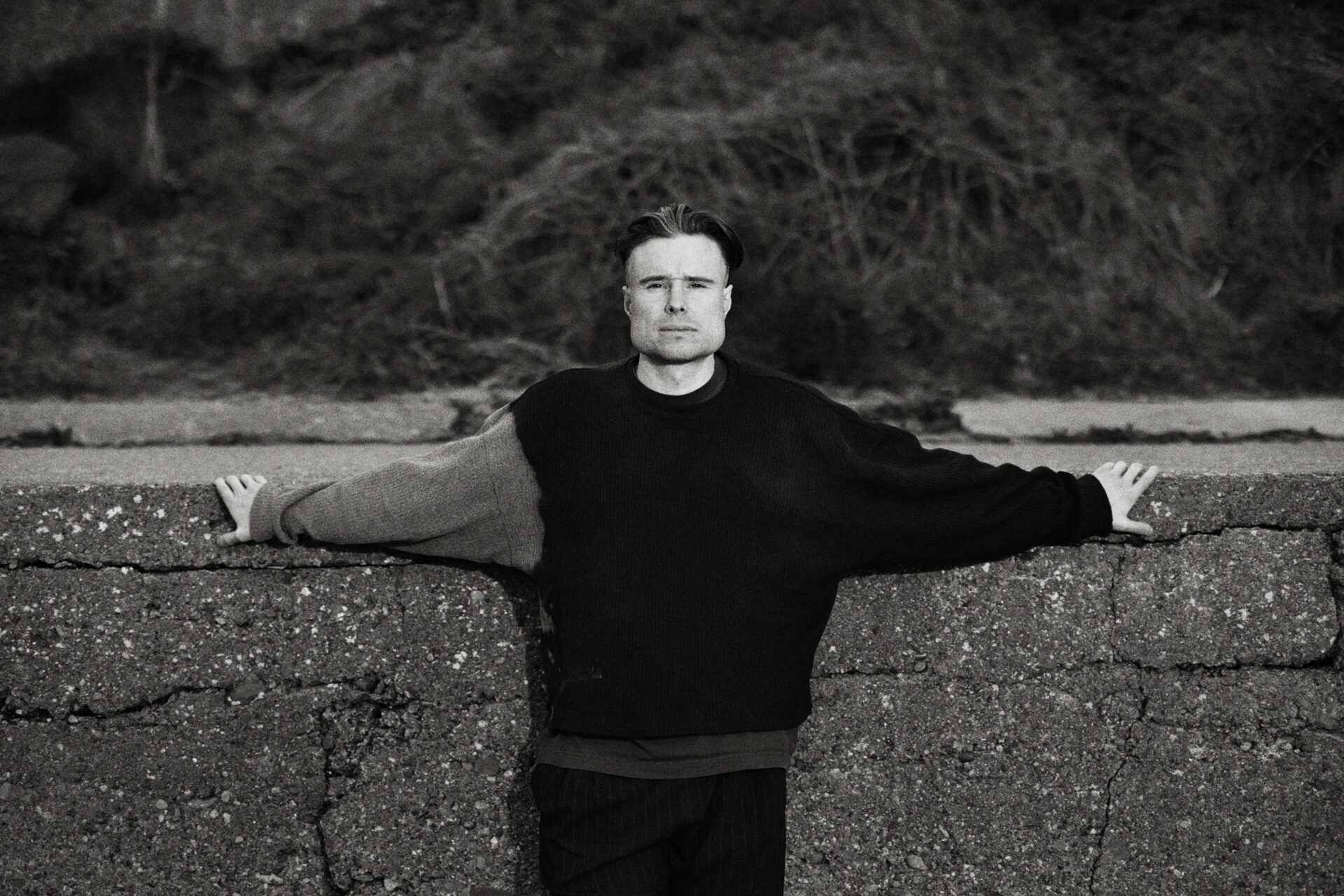

Labour of Love: The story behind For Those I Love’s second album

With the debut album from his For Those I Love project, David Balfe emerged with an astonishing ode to grief. On second album, ‘Carving the Stone’, he zooms out to look at inequality, gentrification and work

Whenever friends would ask David Balfe how progress was going on his new album, he’d tell them the same thing: “I’m just carving the stone.” He’d been using the same phrase for years before to explain how he was moving through tough periods in his life, as if to say: “I’m working on myself. I’m discovering something and I’m chiselling it out.”

Carving the Stone, the second album from Balfe’s project For Those I Love, comes four years after the worldwide release of his astonishing, revelatory debut album. For Those I Love had existed in ripped CD form, circulated between Balfe’s friends and family in Dublin, for a few years prior to its discovery by the music industry.

It immediately demanded a wide release though after those beyond his inner circle discovered his brutally frank, beautifully told stories of his late best friend and the grief that engulfed Balfe and those around him in the aftermath of his death. Over sharp and incisive electronic instrumentals, he dove deep into both the initial crush and the rippling continuation of grief.

Of sharing the story, Balfe told Rolling Stone UK in 2021: “I feel the guilt because there’s an element of personal benefit that I receive from speaking about a tragedy that happened to my best friend and it puts not just his laundry in the street but also that of my peers, of our shared circle, of family. Thankfully these are the same people who are encouraging me to do it.”

Many people, and at times Balfe himself, considered For Those I Love to be a conceptual one-album project, and though Carving the Stone doesn’t as directly discuss grief in the same way as the debut album, its discussions of societal shifts and community-wide issues tackle subjects that naturally relate to the topics discussed on For Those I Love.

“That was an album and a project that I was working on before things in my life changed dramatically, and before the passing of my friend,” Balfe says. “I had made the decision to try and make it a record of love and appreciation for my friends and family. At one point, I had decided that I wouldn’t be progressing further with the name, and that I’d be bringing the project to an end. I then realised that there was more to stay that would fall under the remit of the project. I hope what I have explored on this record is able to reflect some of the thoughts, feelings and frustrations of those that I’m closest with, and fulfil the objective of the For Those I Love project.”

We meet on a stifling day in west London for Balfe’s first interview in years. Writing and conceiving of an album is an insular process, even more so for a self-confessed perfectionist like Balfe, and so sitting down to explain it all for the first time can see new avenues of concepts and meanings reveal themselves to the artist.

During our conversation, as Balfe discusses the creation of the album and its themes, synapses fire and dots begin to connect for the first time. “Maybe that’s something I need to take with me and think about for the next couple of days,” he says after giving one particular – and characteristically erudite – answer. “It seems like I probably do need to think about that…”

Specifically, he was talking about the link between love and labour, a connection that defines Carving the Stone. As a teenager, Balfe would show his love for his friends by making them things. Countless mixtapes (“of pretty bad music!”) were created for friends, while Balfe and his closest friends would host a Christkindl every holiday season. “I’d make a presentation that would tell a semi-fictional story about all of my friends’ years, and what we all did that year,” he smiles. After he broke his leg on the video shoot for the album’s first single, ‘Of the Sorrows’, he spent his time while laid up painstakingly making his partner a teddy bear.

After telling these stories at breakneck speed, Balfe stops and reflects. “Maybe this is the problem, right?” he says. “It’s reflective of some of the themes in the new record. I have always associated labour with love, and that’s a pretty dangerous thing. My dad probably set an example and expectation of relentless graft. My dad’s a driver, and worked so relentlessly and so hard to be able to provide for our family. Maybe, if I was to think about it, that example of relentless labour as a measure of love probably set something off for me.

“I took that example in a slightly different direction, adding in a creative element,” he explains. “I’d be like, ‘I’m gonna make 15 instrumental songs for Robbie, because he’d love to sit down and have a smoke to it at nighttime’.” It’s as if Balfe was saying to his friends: “See how much work I have put in [to show my] love for you.”

“There’s such a danger in that,” he reflects now, continuing to open his own mind as to the crux of his new album. “There’s a connection between the new record, where there is a conversation about the physical, emotional cost of labour, and a very different type of labour that’s much more specifically about actual paid labour and labour conditions.”

He pauses again. “God,” he says to himself, half amused and half concerned. “Am I having a really horrifying realisation that I don’t know how to express love other than with true, intense labour? I really hope not!”

All the work Balfe put in, both on himself and into Carving the Stone, results in a gorgeously rich and multi-faceted album. While For Those I Love introduced him as a songwriter able to transmit deeply personal stories, the new album sees him equally adept at zooming out and connecting the personal and political as an incisive cultural commentator.

‘Of the Sorrows’ powerfully discusses Balfe’s struggle over whether to stay in an economically failing Dublin or leave the place he calls home for somewhere new. “I have to leave / I’ll never leave” go the opposing voices at the song’s climax. It’s a common theme of young Irish songwriters in recent years, and a growing threat for a generation facing rising rents and a country threatened by far-right riots.

“There’s a universal grief in Dublin,” Balfe says of the current moment. “If I would have thought about making a second record, I would have said to myself, ‘It needs to explore something that no other records are doing’. Then when you start to write, you realise the only thing you can write about is the same thing that all of your friends are writing about, because it’s such a monolithic experience.”

Elsewhere, Carving the Stone tells stories of others with the same incisive nature as Balfe told his own on the first album. ‘The Ox’ introduces us to “the big man from down the block” who “made his name as a local fighter” with superbly descriptive language, while ‘This is Not the Place I Belong’ sees him “in bed with technofedualism”.

On the album’s final track, ‘I Came Back to See the Stone Had Moved’, Balfe sings that “my labour bears no fruit worth eating,” losing faith in the building blocks of his life over murky synths and a heavy mood.

At the song’s midpoint, a sample of Jean Ritchie’s 1977 track ‘Black Waters’ filters into the mix, as she sings: “Only black waters run down through my land.” By the end of that song, Ritchie finds “a hope for her land,” Balfe says, and through using the sample he wanted to cling onto some hope for his, too. “For a better Dublin and a Dublin that has new life breathed into it.”

To end the record, gorgeous and life-affirming fiddle – the defining instrument of Irish music – played by Cathal Caulfield traces the melody of ‘Amazing Grace’. “You might usually hear that song as a marker of death,” Balfe says, “but the final line on the album (“I’ll carve this stone until darkness comes / Because I am choosing to live”) is such a deliberate commitment to life.”

It is, he says, deeply intentional to end the album soundtracked by the instrument. “When we hear fiddles playing, it brings about so much joy and a real primal feeling of connection and pride. It was important to me that I was able to take a song that was rejecting pride within your city’s current circumstances, and that couldn’t possibly make any of us in Dublin feel pride right now, and then have this juxtaposition.”

Allowing these two opposing moods to exist together requires going deep into the core of existence, heritage and identity, as he does wholeheartedly across Carving the Stone. It’s quite the undertaking, but Balfe is working on it.

Taken from the August/September issue of Rolling Stone UK, out now. Subscribe to the magazine here.