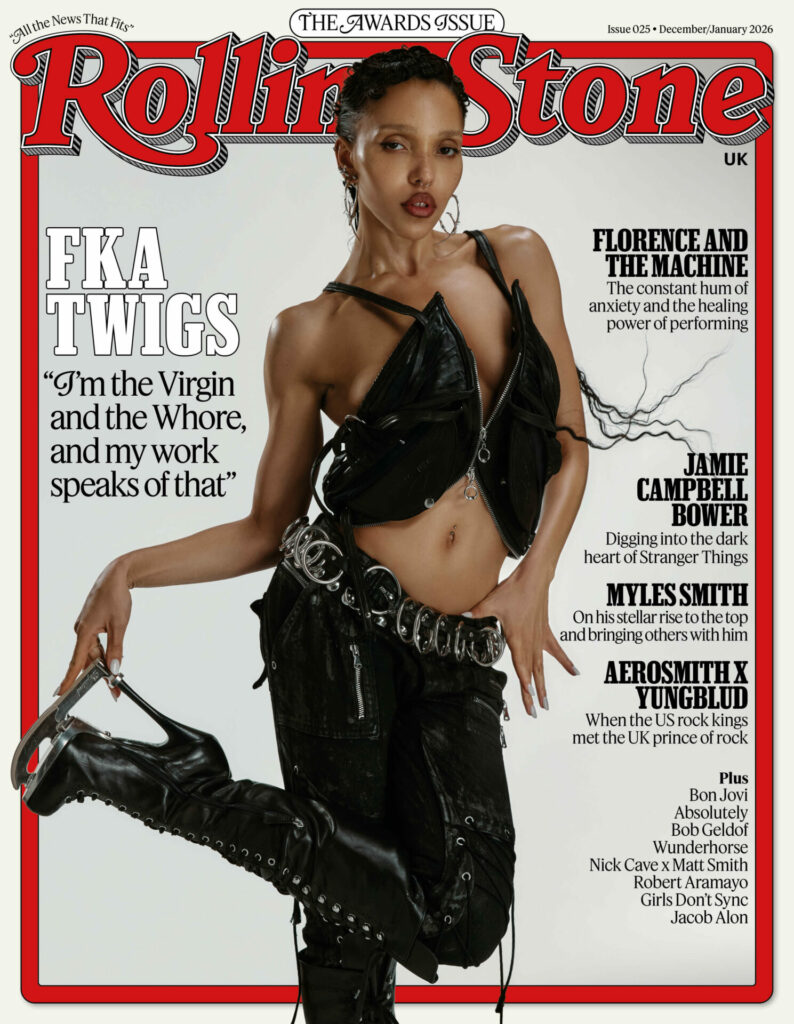

Free spirit: FKA twigs on the lifesaving ‘EUSEXUA’

Our Album Award winner discusses navigating the Madonna-whore complex, and how signing to a major label has given her control of her masters – and her future

By Hannah Ewens

When you were a kid, did you ever pick at cracked paint on a wall until it flaked away beneath your fingernail? The disassociated satisfaction of a small destruction, the curiosity about what lived beneath. That’s what it was like for Tahliah Debrett Barnett aka FKA twigs when she found herself at a rave in Prague in 2022, while in the country filming The Crow. She’d never thought of herself as someone who belonged in a club, yet there she was, caught in the surge of other hypnotised bodies, her limbs moving without instruction.

Maybe it was the shock of being allowed to exist in anonymity, but something like transcendence shot through her. “When I picked the crack in the paint, a beam of light shone through,” she tells Rolling Stone UK. “I kept picking, and more light came, until I saw there was a window behind the wall.” Eusexua – the portmanteau she created from “euphoria” and “sexual”, and the name of her third album as FKA twigs – was that window for her: an escape, but one that led back to herself.

Eusexua was a manifesto about a state of being before it was her musical love letter to the dance floor. Eusexua is kissing someone for hours until your mouth is one with theirs; the split second before an orgasm when time suspends; that moment of Michelangelesque contact between the divine and the human mind, when an idea arrives whole and perfect. It was surrender and simplicity and oneness and it wasn’t just how twigs wanted to make music, it was how she wanted to live.

Everything in twigs’ life had become so “tight and compressed”, she says, a difficult experience for someone hardwired as a free spirit, a dancer since the age of seven. It seems as though she doesn’t want to talk about that time anymore (she becomes deliberately vague, prickles like a cat in the seat opposite me when I try to steer us back to EUSEXUA’s origins), but in a 2024 Vogue interview, she said that when she was in Prague she’d had “intense brain fog” for a couple of years; and told the musician Imogen Heap in a more recent interview, hosted by Spotify, “I was hanging on by an eyelash.” The press coverage of her past five years provides the subtext: a high-profile abuse lawsuit, recovering from said abuse, and the unquantifiable work of psychological and somatic healing. This word she’d made up for herself became a mantra for deliverance from all past earthly suffering.

It feels correct to talk about twigs’ back catalogue as a body of work because her music sounds like a soul entering the body: flighty, sinewy, intimate to the point of terror. Often, it’s called avant-garde – whether for its singularity, or the brief, disorientating jolts of electronic fragmentation. Drawing on her operatic training, her holy voice trembles between confession and prayer. From the liturgical sex-jam ‘Two Weeks’ (2014) to her ruinous piano ballad ‘cellophane’ (2019), she is best known for immortalising her arduous romantic relationships with a personal sort of baroque pop.

But this year’s EUSEXUA suggested a concerted effort to push herself away – and with her, the overbearing celebrity of it all. The album opens with a four-on-the-floor techno beat (or is that a heartbeat?) and her silvery voice, promising listeners that they’re not alone. “People always told me that I take my love too far,” she sings autobiographically, unmistakably herself. Then we enter the club. Her voice becomes a chameleonic cipher as she escapes onto the dance floor: it aggressively raps and gutturally howls, gets Autotuned to hell and back, skips by nasally.

“I always think when I dance, I look so crazy; it’s like everything I’ve ever learned about moving my body goes out the window and it’s whatever feels good”

Over shimmering synths, Eurodance and house, she evokes Ray of Light-era Madonna (‘Girl Feels Good’), artistic forebearer Björk (‘Room of Fools’), fellow weirdo Kate Bush (‘Keep It, Hold It’) and even, perhaps, her British childhood hero, the X-Ray Spex punk, Poly Styrene (‘Childlike Things’). This experience isn’t just about her, of course, it’s about everybody, and every body. Garage-pop bop ‘Perfect Stranger’ celebrates fucking people you don’t know, which transitions into the glitchy, thumping sexual freedom of ‘Drums of Death’ (“Baby girl, do it just for fun”, she ASMRs into your ear). Eventually, she drifts out of the club. Her own recognisable vocals cut through brightly on the early-morning pop of ‘Wanderlust’ – “It’s alright / to be the light / to cross the sea / to wanna ride with higher tides.” The dance floor will be waiting but the sense of self it inspires follows you home.

This was FKA twigs, the musician-dancer-model-actor-activist-performance artist, grazing the edges of a pop-star moment. The album earned her typical critical acclaim –Pitchfork gave EUSEXUA a near-perfect 9.2, and she has since received The Album Award, supported by ZYN, at the ZYN Rolling Stone UK Awards 2025. But it also went to number three on the UK’s official albums chart, her highest position yet.

“When I listen to EUSEXUA now, every sound is like a crystallised piece of water; every sound is like ice,” she says when we speak after her cover shoot. “There’s something so precise about it because it’s the most distilled version of the message.” She lets out a tinkling laugh: by the time this interview is published, EUSEXUA, the original album, will not exist on streaming services in the form we’re discussing. Some of its tracks will vanish with the November release of deluxe album EUSEXUA Afterglow.

“The point that I want to make with EUSEXUA now is that an idea can exist and be perfect at the time, but it’s OK for things to be mercurial and to develop and change.” She’s talking about herself too: the fact that she is (and has been, as we all have) imprinting information such as a viewpoint or an “emotional thing” onto the internet to exist forever is scary. It allows no room for growth, and that is decidedly not eusexua.

It’s a grey day in late October when I meet twigs and two of her team across the road from the Hackney café she’s chosen for our conversation. Wearing a black bomber jacket, industrial chrome earrings and minimal makeup, the 37-year-old looks as if she’s stepped straight out of the world of EUSEXUA. In person, she is younger and more mythically beautiful than through a screen. Her face is a mix of softness and precision that draws your eye to her distinctive cherubic mouth. There must be platforms hidden beneath her flared trousers, giving her a careful, floating height; she seems half-human, half-ancient, like a centaur trying to pass unnoticed.

Our conversation feels tense until something between us – in her, I think – relaxes. She leans towards the outdoor glass fire pit, lit by one of the servers who knows her, and laughs when I bring up her dreamlike track ‘Room of Fools’. “I was nervous to say a room of fools because it feels like I’m calling everyone an idiot,” she says, describing the amoeba-like entity a dance floor becomes. “It has multiple meanings, people moving in this insane, foolish, free, wondrous, childlike way.” Out of context, the word and the bodies dancing, make no sense. “But in the context of everyone moving like that, it’s incredible.”

It made me think of The Fool in the tarot, I mention, a card that signifies new beginnings, adventure and faith in the unknown future. On the Rider-Waite deck, he’s pictured with arms open and face up to the sky, in a gesture of dumb joy. “I always think when I dance, I look so crazy; it’s like everything I’ve ever learned about moving my body goes out the window and it’s whatever feels good,” she giggles, as she often does. “If someone saw me out dancing, they’d think, ‘She’s crazy.’” They’d think it’s FKA twigs and then dismiss you as a weird lookalike, I say. “She wouldn’t do that with her hips!” she shoots back.

Part of her healing process of the past few years has meant learning to inhabit her body differently, to respect the subtle language of her nervous system – flightier now than it was when she was younger. On ‘Sticky’, when she sings the line “You’re right, I hold it in my body / Little snakes inside a bottle / Writhing in my frustration,” she is directing it at her boyfriend, the creative director for EUSEXUA, Jordan Hemingway. He truly reads her physicality beyond the “stretchy, bending and dancing” FKA twigs. “I can do so much with my body but then, when I feel stressed, I can’t do anything,” she explains. “I describe myself as being a sports car. A sports car needs so much maintenance. It needs the perfect fuel. You have to cover it when it’s wet outside. You have to put it in a garage. It really is such high maintenance.”

“It’s my first relationship where somebody knows those things about me – we have a very honest relationship about how we’re both feeling in our bodies,” she continues. “When I don’t feel good, it’s like having these little insects inside my chest and they’re clicking around… the clicking is all the things I need to sort out.”

At the cover shoot a week earlier, I had met Hemingway briefly. He was on a short break between photographing twigs in different looks, when I made a half-joking comment about wanting to be a creative director – that I love deciding what photographers should shoot, which image should be a cover, how it should be cropped. Hemingway caught it immediately. “Honestly, that’s basically all this is,” he said, kindly, and then continued to be a quiet, grounding presence in the room.

That kind of attunement to one another sounds special, I suggest. “I would like to say that’s just being in a healthy relationship, to be honest with you,” twigs says, exhaling lightly, adjusting herself in the chair. “I think we all deserve, with our smallest circle of loved ones, to have people observe and notice how we’re feeling – and for us to observe how other people are feeling. We don’t always have it, but we all deserve it.”

The way she lets herself be seen is central to her presence more broadly – there is something childlike about twigs: the girlish laugh, the sense of wonder when she explains an idea. When she was 18 – still a child, she notes – her youthful nature led men to pin her as a Lolita. Because she looked like a teenager well into her early-to-mid-twenties, she believes she maintained that archetype. “I used to wonder to myself how it would be to get older and have that [childlikeness], because now I am in my thirties and still feel like that.” To be forever young, she adds, “feels fun but it’s vulnerable as well.”

Her childlike spirit is woven into the bouncy, nursery-rhyme-like track ‘Childlike Things’, one of the first songs that twigs ever wrote, at the age of 12 or 13. It was completed for EUSEXUA by her grown self and North West, the 12-year-old daughter of Kanye West and Kim Kardashian, who features on the track rapping in Japanese about God and Jesus. “I feel like she’s seen so much and she’s so mature in a lot of ways, especially emotionally,” twigs says of North West. “We went for a few dinners, and she said things that were big and profound. I felt taken aback by her observations of humility that were very on the nose and very true to the things that I’ve learned as an adult.”

Despite being in the motherly mentor role for the duration of their collaboration, twigs wishes she could have had a friend like her when she was young. “I was bullied at school and didn’t really have that really close girlfriendship, so ‘Childlike Things’ was healing – to give the child in me, who was a bit of a loner when I wrote that song, a tenacious, confident friend like North West, to come and hang out with.”

The day before we speak, I watch the upcoming film The Carpenter’s Son, in which twigs plays Mother Mary, who has escaped with her son, Jesus (The Boy), and her husband, The Carpenter (Nicolas Cage), to hide in an Egyptian village. (Of Cage, she says: “I could feel his car coming through the desert half an hour before he arrived on set. He has that much presence.”) Laying low works for a while – until Jesus’s latent powers are ignited and the devil comes to seduce him. Mary does her best to fill her husband and son with faith; twigs brings a silent strength to the role, acting with her eyes and feminine presence.

“I wanted to pick apart the idea that Mary was meek and agreeable,” she says. “When I studied about her, it’s always ‘And Mary wept with joy.’ I’m like, ‘Why is she always crying?’ I wanted her to have this soft, all-encompassing energy.” The Carpenter’s Son is a hypnotic horror film with, if not heart, then at least a strong moral: to forgive even our greatest enemies. In twigs’ opinion, “That’s what’s missing in a lot of modern filmmaking: there’s no moral.”

A concern for ethical clarity seems instinctive to her. Growing up, she went to Catholic school and is comfortable with religious principles. “Forget what humanity does with religion. Judge religion by its teachings, not its misguided followers,” she says directly. “All religions at their purest form are there to help guide us and help us be good people because at the heart of humanity, we are addicted to negativity. And at the heart of humanity, we do have darkness in our hearts, and we do want to destroy. People say, ‘Oh, I can’t believe this war is happening,’ or ‘I can’t believe this person hurt this other person.’ Why? We’re animals. Why can’t you believe that? Look at nature. Animals destroy other animals all the time just for fun. A fox will go into a chicken coop and kill all the chickens and not even eat any, just leave. Why wouldn’t you believe that we have that in our hearts? The difference is we have a conscience. We have a conscience and we know better. We do have the ability to be able to override that instinct and I think religion is a way to keep us on the straight and narrow for that.”

“I know that about myself as an archetype: I’m the Virgin and the Whore, and my work speaks of that”

It’s curious that she has now embodied the two most prominent women of the Bible: first, the mysterious Saint Mary Magdalene in her album Magdalene, one of Jesus’s closest disciples who was falsely portrayed as a sex worker and sexual sinner due to patriarchal rewriting, and now the other Mary. “How important! I was Mary the Whore and now I’m Mary the Virgin. For me, the two Marys, they are the same Mary,” she exclaims at this observation. “There’s the complex that men have – they can’t accept women as both the Virgin and the Whore – but when we are the Virgin and the Whore, that’s when we’re the most powerful. I know that about myself as an archetype: I’m the Virgin and the Whore, and my work speaks of that.”

She recognised this duality in herself when she was a girl, she says, but was too young to put it into words. “It’s why I think a lot of men have been very perturbed by me; it’s why people have such a strong reaction to my work. It’s complicated,” she explains. “I have a deep innocence, and people say that I’m very ethereal and very ephemeral and there’s this childlike quality, but then if I do a Calvin Klein advert, people complain about it and it gets banned.” She’s referring to the clothing brand’s 2024 advert, which showed her wearing only a shirt, her body simultaneously feminine and muscular. The campaign was initially banned by the ASA, though the decision was later reversed. At the time, twigs responded on Instagram: “I do not see the ‘stereotypical sexual object’ that they have labelled me. I see a beautiful strong woman of colour whose incredible body has overcome more pain than you can imagine.”

There are other contradictions worth mentioning: twigs is exacting and in control – casually mastering pole dancing or wushu sword fighting for a music video because her vision demands it – and she’s feminine and moves fluidly. “I’ve been a ballet dancer and sang opera all my life, but at the same time, there’s such an intense grit inside me,” she says, the flame in glass still burning beside her. She compares her energy to the Hindu goddess Kali, who destroys to create. “I can burn everything down with fire and then know how to build the most beautiful flower that will come out of the scorched earth. You can be both. It’s not good or bad – it just is.”

Her business “FKA twigs” has demanded a similar destruction and rebuilding. After her first EP in 2012, she signed to indie label Young (formerly known as Young Turks), which was then associated with releasing The xx’s Mercury Prize-winning debut. For many years, she was supported to develop as an artist, with a close-knit team who believed in her vision. But a shift became necessary: she chose to sign with Atlantic and worked out a crossover period in which she would release Caprisongs, EUSEXUA and EUSEXUA Afterglow through both labels, before she moves exclusively to Atlantic in 2026. “I just wanted to feel a release from not having to scramble for budgets and beg, borrow and steal – and always be on a hunt as a professional beggar to make my art,” she says of the financial support a major label can provide.

Her heavenly records of the 2010s were recorded very much here on earth. “I made LP1 in my living room in Bethnal Green. Magdalene, I finished in a studio that had a bug infestation because I just couldn’t afford a better studio,” she recalls plainly. On the third day of recording, she felt insane because the wall appeared to be moving. She told co-producer Nicolas Jaar and he went up close to the wall and informed her that no, there were tiny bugs crawling all over it. She quickly undercuts the story: “Now I’m not saying that I’ve made my records in squalor, because I certainly have not. But being signed to Atlantic has allowed me to travel a bit when I make a record and have the budget to go somewhere different.” That freedom meant working in the places that inspired her EUSEXUA ideas: Ibiza, Berlin.

Perhaps this move to a new label was inevitable from the start. “I’ve always really struggled with the idea that I don’t own any of my masters. It’s plagued me from the minute I understood what masters were,” she says and emphasises that I must write this in a classy way, in the spirit of how we are having this conversation. She will continue to love Young and has come of age there – watched the staff’s children grow from babies – but she signed her deal there pre-streaming when deals looked different: “The back end of my contracts is something that I consider to be very archaic and quite oppressive. I’m not blaming them for that.” Shortly after she signed, it became unusual for artists to sign deals for half of their career, for instance. Streaming-era deals can be empowering for artists like twigs who already have a significant fanbase, giving them more flexibility and potential for ownership.

“At the heart of humanity, we do have darkness in our hearts, and we do want to destroy”

twigs has been candid about money before. I often recall that during the coronavirus pandemic, when so many were grappling with financial uncertainty, she spoke of nearly losing her east London home. She nods now in acknowledgment. “The bigger your business, the bigger your expenses are. People don’t really think about that – the more you grow, the more people there are to pay, so everything goes up incrementally.” But she is careful to underline that her perspective has evolved with her career. What she required as an artist in her early twenties is not what she requires in her mid-to-late thirties.

“I am not here talking as a victim of the music industry,” she says firmly. “My wants and needs as an artist have changed, as they should. I’ve never been in a contract where I’ve been deeply unhappy.”

From 2026, her more “favourable” deal means that every future record she makes with Atlantic, she will own the masters to – a fact she thinks sounds ironic considering they’re a major label, the supposed Big Bad of the industry. This transition of power is a weight lifted from her shoulders, she says, to know that she will soon own her art as an artist. “It’s really difficult making under those circumstances when you feel everything you make just goes into this engine that you don’t quite understand.”

For now, though, it has been the comforting presence of Young and the shrewd interventions of Atlantic, guiding the selection of singles, coaxing out hooky melodies, that have carried twigs to a higher dimension. Next year, her stages will swell: arenas rather than halls. The wall is demolished, the window open and she’s crawled right through. “I’m a free woman,” she concludes, smiling, and vanishes before a goodbye can land. It’s a sentiment that could be lifted, verbatim, from a club bathroom door or the liner notes of EUSEXUA.

Photographer: Melanie Lehmann

Creative Director: Jordan Hemingway

Stylist: Billy Lobos

Hair: Louis Souvestre

Make-up: Catalina Sartor using Tom Ford Beauty, Gucci Beauty and Mac Cosmetics