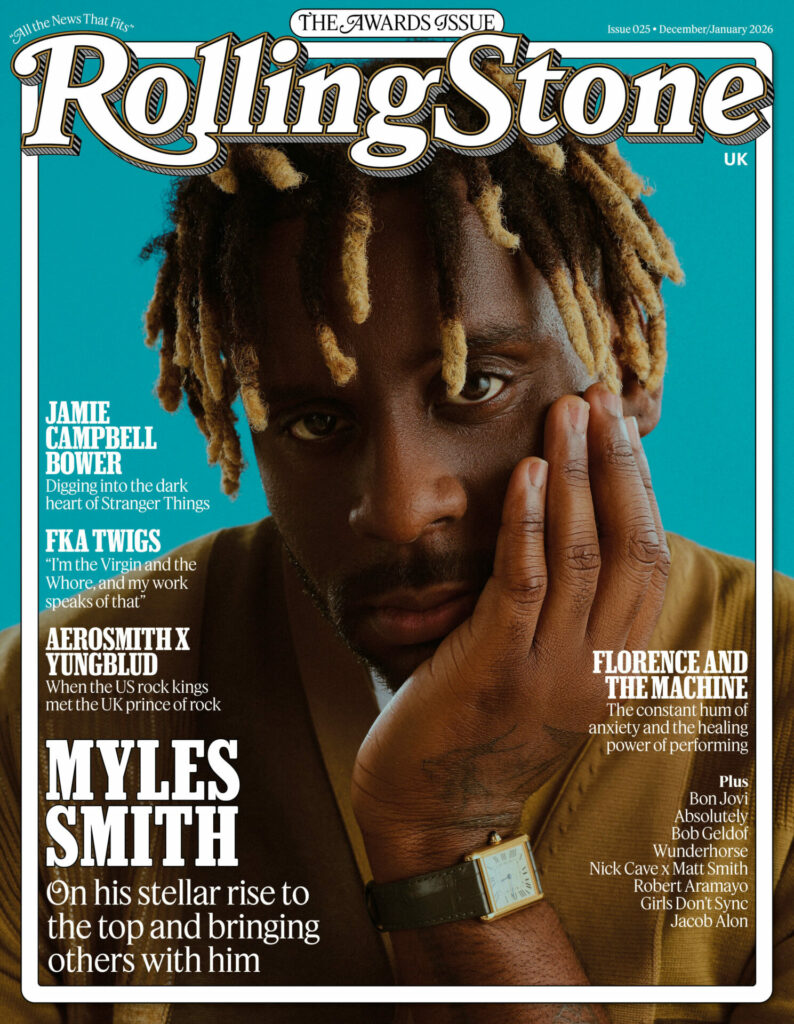

Myles Smith is the UK’s next everyman superstar

With hundreds of millions of streams and a determination to give back and demand more, the Luton singer has a heart as big as his voice

If you’re a young musician looking for a hero and a role model, you might choose someone with an otherworldly quality that makes you feel like you can transcend yourself. Bowie, Prince, Gaga. In his early twenties, Myles Smith was a business owner in strategic development, but he was determined to take his musical dreams off the backburner. He picked Ed Sheeran as his North Star – not entirely because of the sold-out stadium tours, international acclaim and millions in the bank. It was because he seemed so damn nice, and so damn normal.

In Sheeran, Smith saw a way to make music, connect with an audience and still keep a hold of himself. Though many promotional campaigns around up-and-coming artists are built on establishing faux-authenticity and an everyman aesthetic, Smith looks and feels like you because he simply is. His story – from a working-class kid in Luton to a BRIT-winning, chart-topping sensation – is full of false starts, unglamorous details and unseen hard work, and is all the more relatable for it.

When Smith did eventually meet Sheeran – the pair attended an Arsenal match at the Emirates Stadium at the end of December 2024 – he was struck by the complete lack of difference between his public persona and private demeanour. It showed him you can be entirely yourself and still become a beloved, important artist. It’s an ethos that Smith has maintained through chart-topping singles, worldwide tours, his first Rolling Stone UK cover and now with his win of our Breakthrough Award. Whatever shiny accolades come his way, it’s only worth it, he says, if he remains “just Myles from Luton”.

Myles from Luton was born in 1998 into a working-class British Jamaican family. “I didn’t grow up with a lot of means,” he says today, speaking in London in between a continuing whirlwind of touring, promotion and work on new music that’s meant he hasn’t spent more than four days at home in a row during the whole of 2025. “My mum always talked to me about the path in life, which is about education and finding success in that way,” he explains. “She was very motivating, so even when I wasn’t doing well at school, she’d be the one to sit and go through my books with me. If I was struggling with my exam, she’d be the one that would walk me to the exam room and be like, ‘OK, you got this.’” He says he’s extremely aware that “not everyone who grows up in my environment has that level of parenting where those things are pushed,” and credits his life going down the right path to that support.

At 18, Smith sat his mum down at the Red Lion pub in Luton and told her that he wanted to pursue music. She said to him, “If you want to do it, I’m more than happy for you to do music, but I just want you to promise me that you’re going to work every day and you’re going to put your complete self into it.” In that moment, Smith realised that he had to take his mother’s earlier advice and build his life around an education instead. “I don’t think I was ready to take the leap of not having that to fall back on,” he reflects now.

From there, Smith gained a sociology degree and started his own business in management and strategic development. By 23, he was successful, financially stable and yet unable to shake a nagging feeling of unrealised potential. “I was in the apartment that I wanted. I had the car that I wanted, and it didn’t bring any fulfilment,” he says. “It’s a real privilege to not have to stress about bills or stuff like that, but when I was playing in a really shitty indie band in a pub, I felt that this is where I belong. That’s a better feeling than just being able to say that by the time I’m 50 or 60 I can retire because I’m in a good pension scheme.”

Of course, another summit with his mum followed, and Smith remembers her answer verbatim: “I was waiting for the day that you’d say you wanted to do music again.”

When Smith did return to music, Sheeran’s example still lighting the way, he found a new perspective and depth to his songwriting after existing in what he calls “the real working world”. Inspired by the ‘stomp clap hey’ folk revival of the 2010s, as well as the stadium-filling sounds of Sheeran and Coldplay, the music he made was big, bold and felt genetically engineered to raise the hairs on your body.

His 2024 single ‘Stargazing’ became an omnipresent behemoth in the charts, on the radio and out on the street last year. While the pressure was then inevitably on – from Smith internally as well as from a rapidly growing fanbase – to repeat it, it was again his experience of a “normal” life that told him to put the brakes on rushing out an album to build on the runaway success of his hit single.

“Commercial success is a bit like going to the casino,” he says. “When you win, you’re like, ‘Oh, I want more of that,’ but you’ll find yourself putting out records that you don’t love completely, just for the chance that they might do that thing again. My internal barometer now says that if I think something’s OK and I put it out and it doesn’t do well, I’m gonna be miserable. If I think something’s OK and put it out and it does do well, I’m gonna be miserable – I’ll have to play it every single night. ‘Stargazing’ was a pocket in my life that I really love, and I don’t think I’ll ever be able to recreate that song.” As he told himself and his label while the song was continuing to blow up: “Why would I put out an album if I don’t have an album’s worth of things to talk about?”

“Being able to build a community from authenticity rather than guardedness is the kind of artist I want to be”

Instead, Smith showed more of his artistry and the deeper, more subtle layers to his songwriting through last year’s EP A Minute… and this year’s follow-up, A Minute, A Moment… Of course, more undeniable radio hits snuck through regardless – the enormous ‘Nice to Meet You’ and barnstorming new single ‘Stay (If You Wanna Dance)’ – but it was the single ‘My First Heartbreak’ that pricked ears up the most.

On the song, Smith frankly discusses his feelings around his father leaving his family routinely between the ages of seven and 13. “I wish when I was younger I hadn’t put all of my faith into you,” he sings, later making the devastating acknowledgement that “my first heartbreak looks a little bit like me”.

‘Stargazing’ arrived at a point where Smith was “still trying to figure out my artistry”, he says, adding: “I knew I could write songs that I love, but I always straddled the line of, ‘How much of me do I want to put into a song? How much of my story?’ Every song is me and every song is a story, but there’s a difference between that and saying there’s family drama and me and my dad have fallen out, my sister’s had this issue and my brother’s had that issue. The more that I spend time playing live shows, and the more that I see how people connect to music, the more I feel comfortable doing more of that. Being able to build a community from authenticity rather than guardedness is the kind of artist I want to be.”

In between his touring commitments, Smith has spent almost every spare minute decamping to a series of Airbnbs across Europe to piece together what will become his debut album. “My mission statement is to write songs that don’t necessarily end with a pretty bow,” he says of the record’s thematic core. “It’s telling things for what they are. As people and as humans, we exist not in the black or the white – it’s the grey.

“There were so many times in my life where I used to write songs that basically said: I was heartbroken, then I figured it out, now everything’s OK. But the reality is: I was heartbroken, it was really shit, and it’s still really confusing. There’s family drama, I’ve gone to therapy and it’s still really confusing, and there’s still stuff I’ve got to figure out. It’s about the project trying to be more human in that it might not answer any questions, but it will just make you more comfortable knowing that being uncomfortable is OK.”

Privilege is a common and thorny topic in conversations around new artists, especially British ones, these days. Most of it revolves around digging up where a certain new singer went to school, or the high-powered jobs their parents might have. For Smith, he says his own form of privilege comes from his mum pushing him to become self-sustaining by 23 so he could then take the risk on music on his own terms.

As a child, he also had the (now rapidly disappearing) privilege of a government-funded arts programme at his school. “If there wasn’t a Labour government with a poorly costed arts funding plan, I would never have had a guitar,” says Smith. “It’s scary to think about how life could have turned out if I didn’t [win] that postcode lottery and go to the one school in the area that had the Building Schools for the Future funding.”

This lack of funding then creates vicious circles of a lack of access and subsequent demonisation, especially among Black communities. “You can’t access instruments or live shows, so kids make trap or drill with the means that are accessible to them,” Smith offers. “That genre of music is then denounced for not being artistic. They’re stuck in a cycle: ‘I can’t go and play live instruments and I can’t record in a live studio, so I bought myself a laptop and put together a loop sample with some drums and made it go viral on the internet. But everyone’s telling me that the experience that I’m growing up with and the style of music I’m making just isn’t culturally acceptable.’ What else are they supposed to do?”

With this frustration foremost in his mind, Smith has used his most high-profile moments yet to demand better. On stage at the 2025 BRITs, picking up the Rising Star award, he told the government on live TV: “If British music is one of the most powerful cultural exports we have, why have you treated it like an afterthought for so many years?” He then went on to say: “How many more venues need to close and how many more music programmes need to be cut before we realise that we can’t just celebrate success; you have to protect the foundations that make it.”

“What is the point of me getting to the point that I’ve got to without using my platform to say something, to initiate change?”

A few months later at the Ivor Novello awards, he joked: “If you know me from the BRITs, you know that I like to talk a lot of shit about things we should change,” before yet again demanding more. “Writing songs is the lifeblood of music,” he told the raft of music executives in the room, highlighting the issue of underpaid and underacknowledged songwriters. “It’s the thing that keeps this industry going and is the most important thing. That should be recognised.”

It is maybe unsurprising that it was Smith’s mum who made him like this. “What is the point of me getting to the point that I’ve got to without using my platform to say something, to initiate change?” he says plainly. “I think that’s the part that scares me the most – so many people have the mindset of, ‘I struggled, I grinded and I went through heaps and mounds to make it to the place that I am, so everyone’s got to do it that way.’ I’m of the mindset that I struggled and I did way too much to be able to get to where I am. Why the hell do I want someone else to have to go through that to do the thing that they love? My mum always said to me, growing up as a working-class Black British boy, that wherever you go, make sure you leave a ladder behind you. Make sure there’s a way for other people to do what you do, because ultimately, that’s the only way we’re going to be able to better society and better the place that we come from.”

Despite Smith putting normality and a refusal to play the fame game at the centre of his rapidly growing career (“I’ve never had a fascination with being called famous,” he says. “I still cringe when people say it”), those who adore him don’t always return the favour. A week before we meet, Smith took to Instagram to describe how a number of fans had found his travel itinerary online and followed him to an airport, buying plane tickets to get through security simply to get close access to the singer and film him on their phones.

He wrote at the time: “If you think digging up private travel plans… tailing me while filming, and following me to the plane door is just part of my job, you are wrong. My work might be public-facing, but my boundaries still matter.” It’s reminiscent of a similar message from Chappell Roan in 2024, who told fans: “I don’t care that abuse and harassment, stalking, whatever, is a normal thing to do to people who are famous. That doesn’t make it normal. That doesn’t mean I want it, doesn’t mean that I like it. I don’t want whatever the fuck you think you’re supposed to be entitled to whenever you see a celebrity.”

It’s an ongoing battle for Smith, and in some ways the trickiest part of this whole thing to navigate as he continues his lightning-fast trajectory towards superstardom. “Anyone who understands the world knows there should be a natural boundary between saying hi or taking a picture and then somehow finding out flight information and buying tickets to make it through a security line to follow someone to a plane,” he says today. “There’s just a level where it’s like, ‘This is odd.’

“By no means have I ever been a victim of stalking,” he clarifies, “but I imagine there are similarities in that. We may know someone and we may be close to them, but there’s also a boundary of day-to-day human relationships. I wouldn’t follow my friends home just because they’re my friends. I wouldn’t follow my mum to whatever she’s doing privately just because she’s my mum. There should be a certain degree of boundary-setting in any relationship, whether that be someone in the public eye or someone just living their life.”

For Smith, it’s a case of putting good energy out into the world, demanding progress for everyone and hoping this positivity and warmth radiates back onto him from others. In order to achieve this and avoid as many of the traps and temptations of the world of fame, he operates a sober, joyful and – above all – kind ship on tour. Most of his bandmates are friends from childhood and university, while “outrageously” talented 19-year-old Eddie Lopes has recently joined on bass. Paying it forwards as always, Smith says proudly that he and his bandmates have created a strong, stable support network around the youngster. “He’s seeing it as a career, rather than going wild on weekends and then coming back home,” he smiles.

“We all are so committed to being the best live performance band in England,” Smith adds of his band, who have played stadiums with Sheeran and huge slots at Glastonbury and beyond this year, as well as a performance at the Rolling Stone UK Awards. “We really want to make a dent, so it’s all about the music and the culture. It’s all about keeping ourselves performance-ready.”

To do this, an abiding principle was drawn up. “We want venues to remember us as a band that causes no issues and everyone’s polite,” he explains. “We’ve got rid of people from our crew before, and we make sure that we have a certain culture, and we look after each other, and we talk.”

“My mum always said to me, growing up as a working-class Black British boy, that wherever you go, make sure you leave a ladder behind you”

As with most inspiration in Smith’s career, this ethos is one he learned from Sheeran. “The unwritten part on the job application for anyone joining is: are these people good people?” he says. “Everyone that you meet in the industry will say Ed’s a nice person. It’s not an act – it’s because he and his team completely care.” It sounds simple – even cliched – but is fundamentally just normal and to be celebrated. “I just don’t want to be remembered as a dick,” Smith says. “I’ve met way too many dicks to want to be one.”

Just before he departs our cover shoot, talk turns to evening plans on one of precious few free evenings for Smith in a year when the pace is not letting up. I ask whether he’s going along to watch his beloved Arsenal play Olympiakos in the Champions League – surely, as a diehard Gooner, he is front of the queue for box seats these days? He can’t, he says. He didn’t get enough tickets to bring all of his friends along and didn’t want to leave anyone behind. They’ll watch it all together on TV instead. In Smith’s utopian but also completely achievable world, everyone’s got to be along for the ride – or no one is.

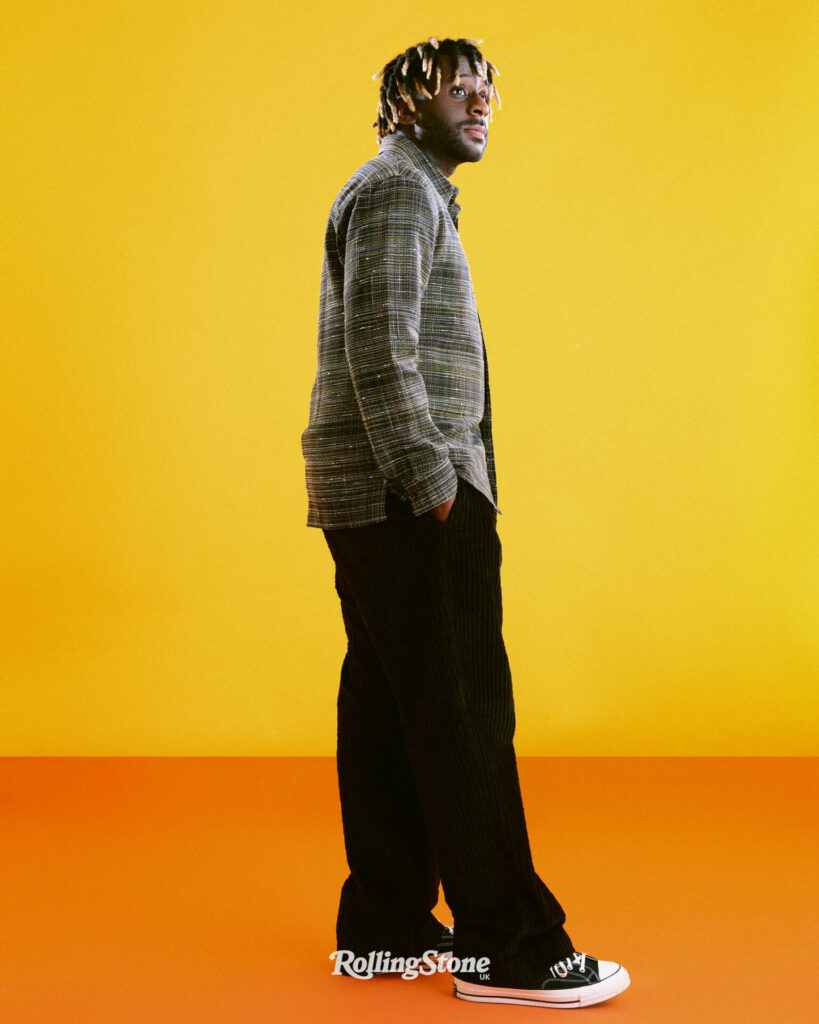

Photographer: Melanie Lehmann

Stylist: Daryon Imprey

Grooming: James Bickmore at Joe Mills Agency using RMS Beauty and Apostle