‘Original Ravers’: Peter J Walsh’s new photobook spotlights the faces behind the Haçienda

Read an exclusive excerpt from the new photobook from the British Culture Archive

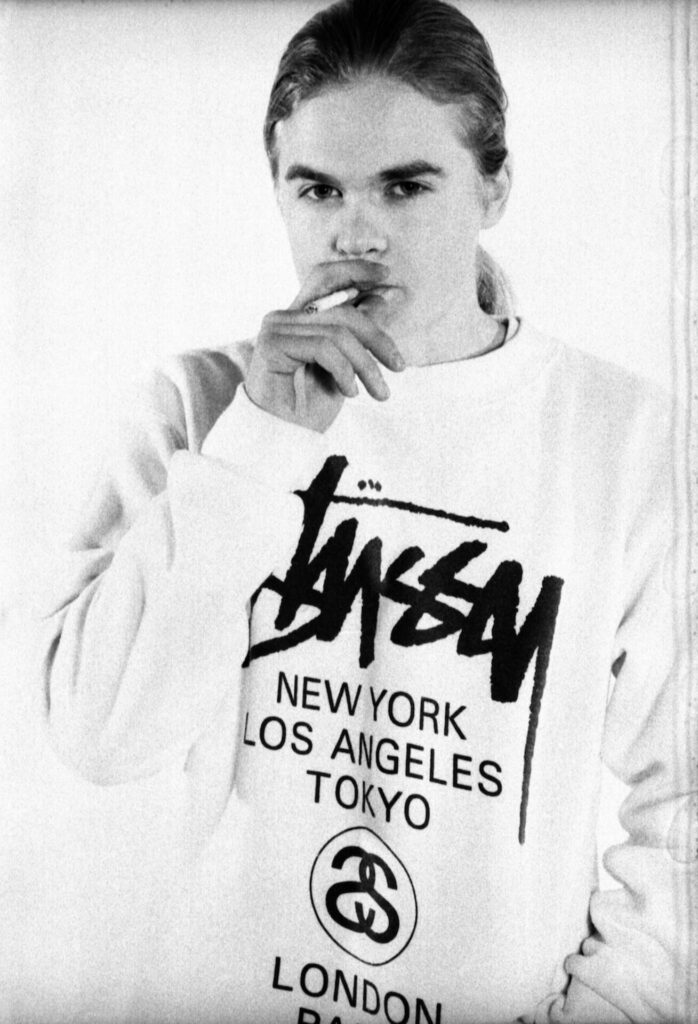

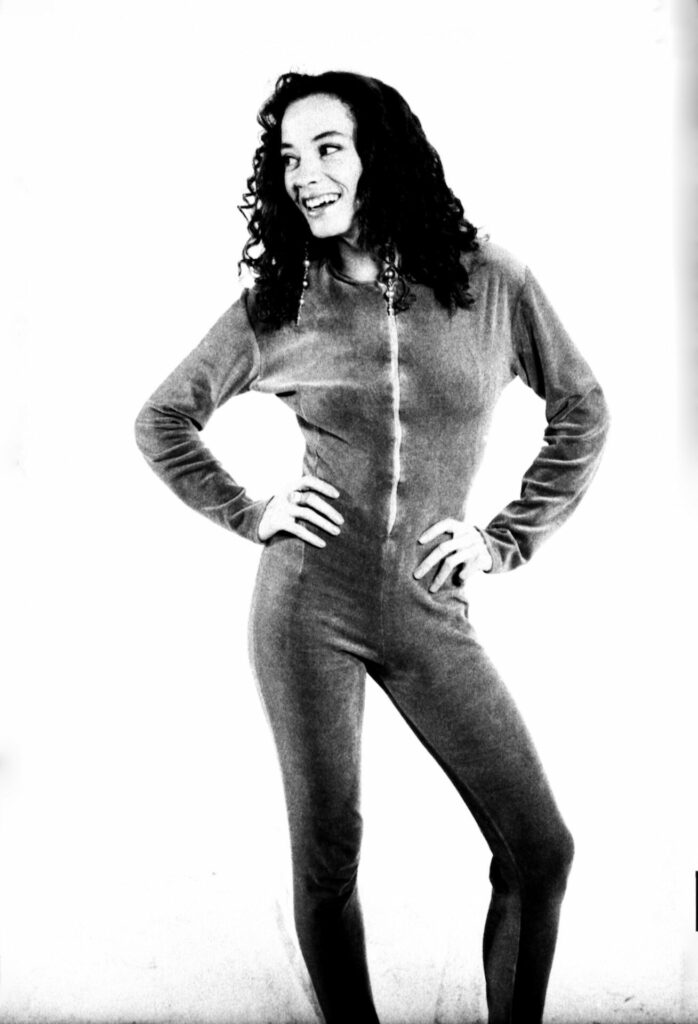

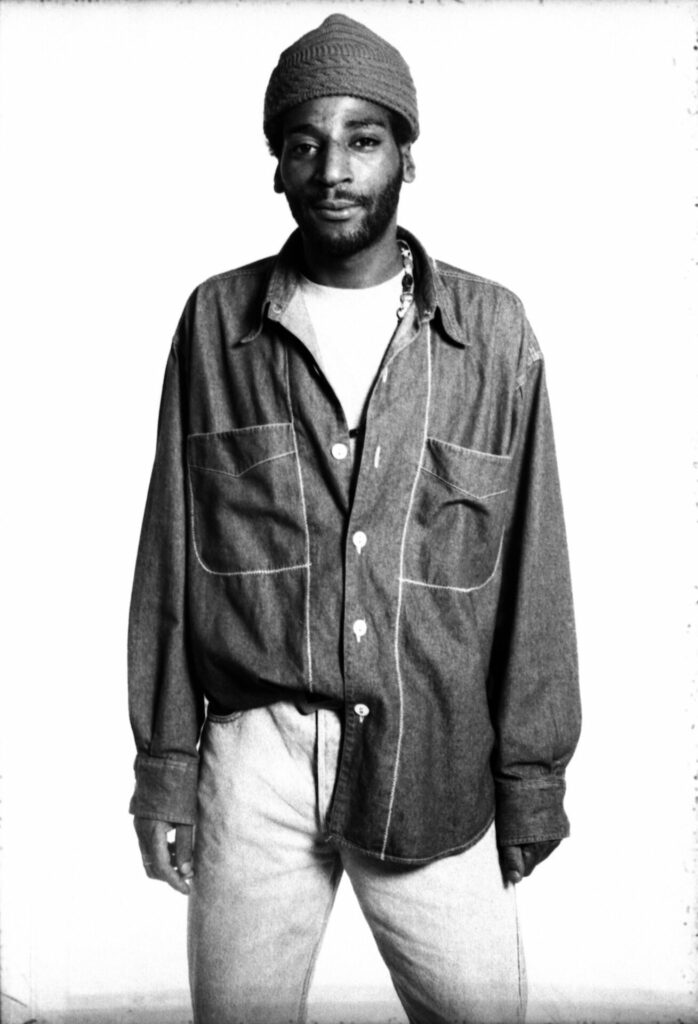

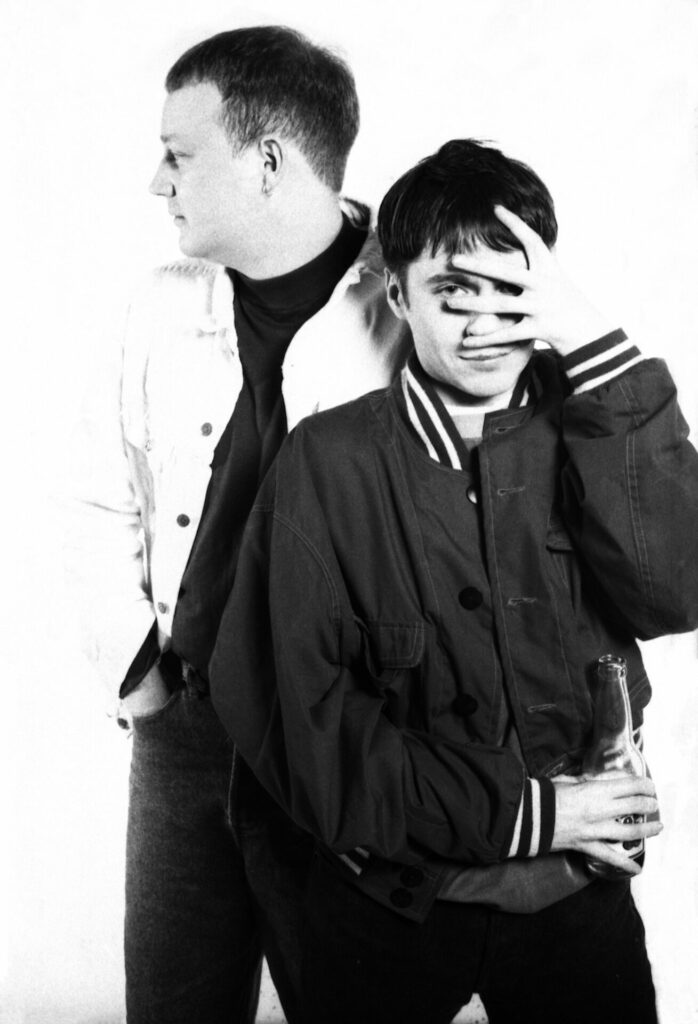

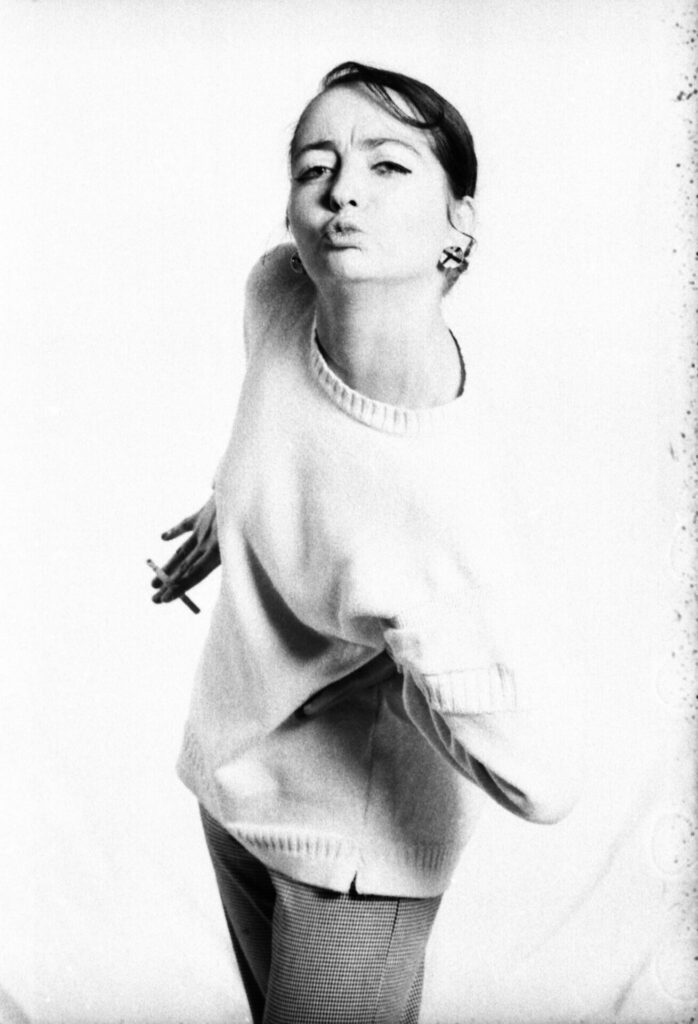

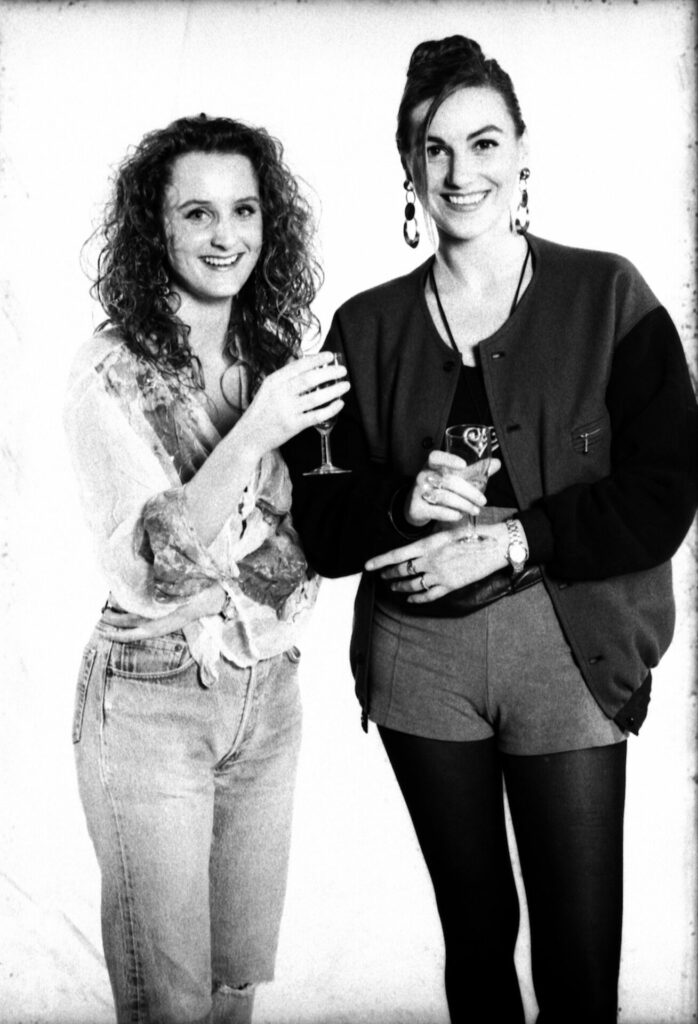

Original Ravers, the new photobook from Peter J Walsh, shines a light on the people behind some of the UK’s most memorable parties.

The release is the second photobook from the British Culture Archive, following Not Going Home, the recent book from Mischa Haller that spotlighted the lives of ravers after the clubs closed their doors in the early hours.

“Peter J Walsh was at the epicentre of Manchester’s groundbreaking acid house, club, and rave scenes. Immersed in a cultural revolution, he documented the faces, fashions, and spirit of The Haçienda dancefloor as the city became a global epicentre for music and style,” the Archive’s founder Paul Wright said.

“The arrival of ecstasy and the rise of club culture broke down barriers of race, class, and sexual orientation, uniting a generation during a period of political turbulence. The fashion — loose, baggy, and unpretentious — was designed for freedom of movement, a stark contrast to the strict dress codes of 1980s nightclubs. At The Haçienda, anything went. It was about the music, the atmosphere, and the shared experience of like-minded people.”

Of Original Ravers, Wright added: “The Original Ravers portraits—previously unseen and unpublished—have been recently scanned from Walsh’s extensive archive. Together, they offer an intimate and vivid time capsule of the era, standing as a vital record of one of Britain’s most influential clubs and cultural movements. These images capture a pivotal moment when Manchester redefined the landscape of music, fashion, and youth identity.”

See a gallery of portraits from Original Ravers and read an introductory excerpt from the book by Walsh below.

I remember when Paul Cons, the events manager at The Haçienda, called me to let me know that The Haçienda would be closing. The news of the closure came as a shock to me. I had been covering the birth of Acid House for the NME, The Face, and i-D for several years, and The Haçienda was the central hub of this cultural movement in Manchester and beyond. I was also a regular at the club on my nights off. The closure would be a terrible loss, not only for the staff, who would lose their jobs, but for the Manchester ravers and those who travelled from all over the country to party inside its hallowed walls.

It was true to say that there had been problems brewing at the club for some time. The rise of violence at the door and inside the club from various gangs competing for the drug trade had been intensifying. Bouncers and other members of staff were being threatened regularly, and people were getting hurt. Guns were being pulled by the gang members on the door staff, who had no choice but to let them in. There were even stories circulating that, at one point, a gang member pulled out an Uzi submachine gun in the Gay Traitor bar, but somehow he was bundled outside by the security team without any shots being fired. The Haçienda management were, quite rightly, very concerned that somebody was going to get killed. They asked for help from the police on many occasions, but to no avail.

James Anderton, known in Manchester as ‘God’s Cop,’ was the Chief Constable in charge of Greater Manchester Police at the time, and as such was fully against any type of hedonism and escapism that The Haçienda provided. He was quite happy for the club to close. I’d been photographing the ravers, the staff, the bands, and the DJs there regularly for over three years.

Heartbroken by the situation and the decision, I wanted to document the people who were there on the final nights of The Haçienda. I called Paul and talked to him about the idea. He was up for it and told me I could use the basement to set up the studio. There was a door in the Gay Traitor bar that led directly into the basement, and I could use this for access.

When I got down there, it was full of old props, lighting equipment, and about a hundred barrels of booze. I found a space I could use and worked out that, if I hung a cloth backdrop from some of the anchor points in the ceiling, it could work well. I wanted the portraits to be black-and-white, high-contrast images. This was 1991 — still several years before digital photography or Photoshop was available.

I started taking test shots and processing and printing the results. Using normal film developer wasn’t giving me the images I wanted, so I decided to try paper developer to give me the grainy texture I was looking for in the negatives. After several attempts, I got the results I was after.

On the Friday and Saturday nights before the closure, I went into the club early and set up the studio space. Then I just had to wait until the club was at full tilt. My assistant Leslie, who was a regular at The Haçienda, did an amazing job of pulling people off the dance floor and bringing them down to the basement to be photographed.

It was cold down there — it was the end of January and there was no heating. That’s why some of the people are wearing coats, jackets, and sweatshirts. Four days later, on the 30th of January 1991, I went to The Haçienda for the press conference. Paul Cons and Tony Wilson were in attendance. Tony looked tired and drawn. He read from the press release, stating that The Haçienda would close with immediate effect. We didn’t know whether the club would ever re-open again. – Peter J Walsh

Original Ravers is out September 23. You can pre-order your copy here.