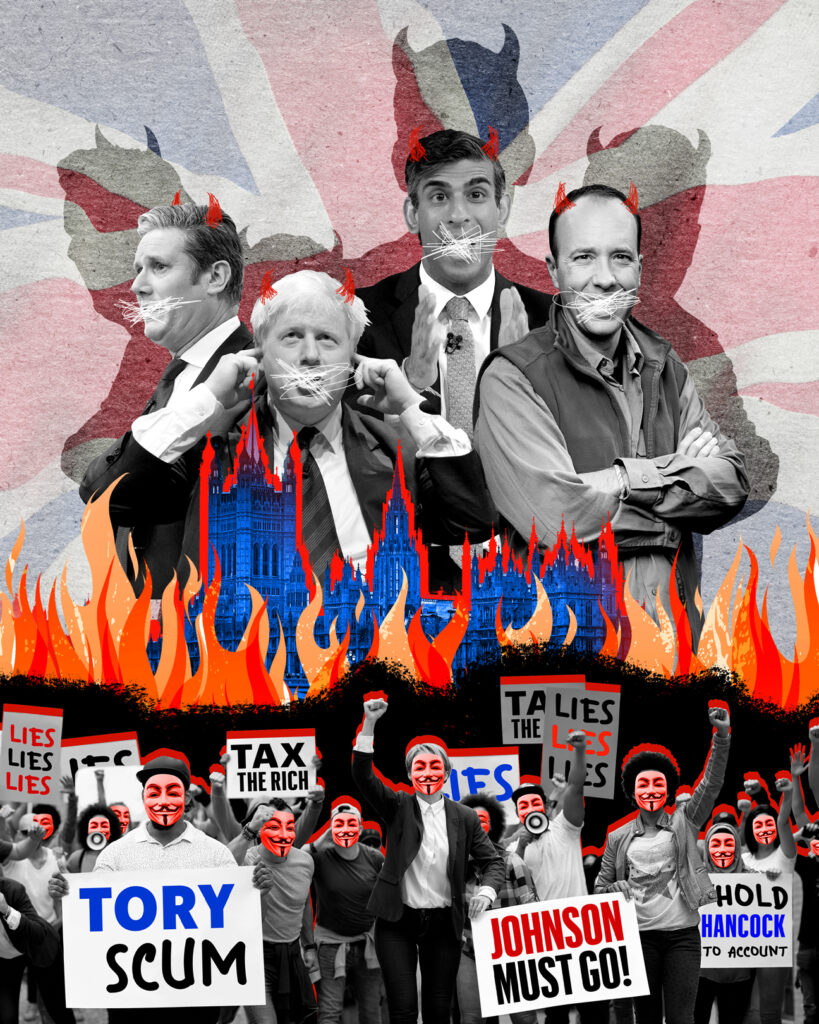

Can we restore the UK’s faith in politics?

Trust in politicians is at an all-time low as a result of lies, second jobs, obscene wealth, Conservatives doing favours for friends and the ever-revolving door of Tory PMs. Whether it’s possible to turn this around is yet to be seen, as Rolling Stone UK reports

By Emma Garland

Just before Christmas, Matt Hancock — the current MP for West Suffolk and former Health Secretary who presided over one of the worst death tolls in the world during Covid-19 — was munching on a cow’s arsehole in the name of light entertainment. With a public inquiry into the government’s handling of the pandemic underway, Hancock entered the Australian “jungle” to compete on I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! 2022.

It was a decision that Lobby Akinnola, a spokesperson for the Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice campaign, described as “sickening”. “If he had any respect for the families like mine, he would be sharing his private emails with the Covid Inquiry, not eating bugs on TV,” Akinnola said.

Speaking to the Mirror, one Labour source added that it would be a change for Hancock to be “eating b******s rather than talking it”. For its part, the show saw a huge boost in ratings, with 9.1 million viewers tuning in to watch the disgraced politician gag on animal genitals during his Bushtucker Trial. In early December, Hancock announced that he will not stand as an MP at the next election.

This particular situation reflects the mood of UK politics in general. With the Tories spending most of 2022 in leadership chaos and Labour haemorrhaging both members and donors, the two major political parties are experiencing a crisis of internal identity and public confidence. A study by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) found that trust in UK politicians is at its lowest level in decades, with 63 per cent of voters viewing politicians as merely “out for themselves” (up from 35 per cent in 1944, and 48 per cent in 2014). This study was published in December 2021 — before Sue Gray released her report into the multiple “gatherings” held in Downing Street during Covid lockdowns, and Liz Truss tanked the pound before being ousted by her own party after just 44 days in office — so presumably that figure is even higher now. The issue of trust was raised again recently by Daniel Greenberg, the new parliamentary commissioner for standards, who acknowledged that we are experiencing a “low point in the reputation of politics and politicians” and that “politicians as a class definitely have made some mistakes”.

Politicians have always been thought of as dishonest and self-serving, to an extent. For example, the UK’s invasion of Iraq in 2003, based on what would turn out to be deeply flawed intelligence, was a significant turning point for public trust in government — particularly in relation to military action. Dr Jamie Gaskarth, whose 2020 book Secrets and Spies explores accountability in 21st-century politics, writes that the Iraq failure “has affected political responses to crises ever since, from Syria to the Salisbury poisonings”. However, the more recent back-to-back upheaval of Brexit, the 2019 General Election and Covid-19 — all of which have come with their own catalogue of broken promises and controversies — has led to a sharp decline of faith not just in government, but in democracy itself.

“It’s almost like audacity has become the norm,” says Alastair, a 37-year-old fintech worker from Bridgend, whose disillusionment settled in during the pandemic. For Alastair, it was hard not to “give up entirely” when multiple government officials were breaking their own lockdown rules and helping to award contracts worth at least £1.7bn to private companies with ties to the Conservative party. “A lot of people were sympathetic of Boris’ efforts — ‘it’s a tough job’, blah blah blah — and it was clear that the fast-tracking of connections and bypassing of public sector procurement rules were going to go unpunished,” he explains. “There also seemed to be a higher level of tolerance for [bad behaviour]. Numerous documented and well substantiated cases of bullying, cheating and abuse were forgotten about by the public and media almost immediately.”

“I guess you could say that the sheer volume of crises has created nihilism and apathy in voters,” Shaun, 32, from Manchester, agrees, “meaning politicians are able to get away with more than they were.”

This particular era of cynicism can be partly attributed to how transparent corruption has become under the current government. As Isobel, 28, from Hampshire puts it: “I didn’t trust them much before, but I certainly trust them less now.” However, it’s not just the unholy trinity of Brexit, the 2019 election and Covid that’s leaving people jaded. “For me, the worst thing has been the turnover of Prime Ministers,” Isobel says. “The Tories are clearly doing whatever they can to cling on to power rather than attempting to actually govern. It’s so blatant that no one is running the shop. I mean, we literally had a PM who was outlasted by a lettuce.”

Things don’t look particularly rosy for the opposition either. Alastair and Shaun have both been lifelong Labour voters but don’t have much faith in the current leadership, which seems to be the definitive theme for the party at present. An exodus of members post-Corbyn has gone hand in hand with an ousting of more left-wing MPs, such as Sam Tarry being removed from the front bench for joining striking RMT workers on the picket line. With everyone from rail and postal workers to NHS nurses on strike and wealth equality — which was already among the worst in Europe — on the rise, a growing number of people are wondering who the House of Commons are meant to represent.

“The Tories actually deliver a fantastic mandate for the incredibly rich people who call this island home, so they’re doing exactly what’s expected of them,” Shaun sighs. “With the Labour party there are two expectations running concurrently: get the Tories out at all costs and deliver for the workers of the country. But New Labour edges towards the centre right by claiming that centre right policies are how they achieve that first goal of getting into power, which is demonstrably false.”

Isobel has less political allegiance, having voted for the Liberal Democrats, Labour and Green in previous local and general elections. Going forward, she reckons she’ll “begrudgingly” vote for Labour, however, she agrees with Shaun’s assessment of the party. “Tony Blair abandoned Labour’s working-class roots in the 90s and formed a New Labour for those aspiring to become middle class,” she says. “But after a decade and a half of recessions, the middle class barely exists. So… now what?”

One issue that cuts across the whole political spectrum is an ever-worsening quality of life. The economic impact of Brexit, Covid-19 and the global energy crisis has compounded 13 years of Tory austerity and cuts to public services, leaving Brits facing the sharpest fall in living standards on record. Following Rishi Sunak’s plan to plug a £55bn fiscal hole through tax rises and further spending cuts, Ryan Shorthouse, who founded the influential Conservative think tank Bright Blue, will walk away from his role. He cited the party’s “betrayal” of millennials and lack of vision to address issues such as stagnant wages and the “punishing” cost of housing and childcare — things he describes as “the building blocks of what Conservatives believe make the good life”. Though he didn’t comment on whether he would continue to be a member of the party, he described Rishi Sunak as “short-sighted” and the party as “tired” and in desperate need of a refresh. “Politics has a profoundly serious talent problem,” he told the Guardian. “The Tories have worsened it: Partygate, the continuous plotting and bad behaviour has made politics seem an even more poisonous profession.”

“Ideally an elected politician is expected to be entrusted to deliver what they promised when their constituents voted them in,” Alastair says. “Counter that with the current scenario where there’s yet another unelected leader, and is it any wonder people are disconnecting from it?”

Declining political trust often leads to looser party ties — something that, in their report, the IPPR warns “makes it harder for leaders to achieve consensus to take bold action using state power to solve problems”. It also creates more room for populism. According to recent data from Ipsos, people are more likely to trust their local MP than MPs or the government in general, which could impact the way the UK votes in the future.

In the next election, Alastair and Shaun plan to switch their support to the Green Party. “For me it’s the integrity around wanting to encourage every young person to partake in democracy, and the move to proportional representation in future,” Alastair says of what the Greens offer that other parties currently don’t. “A lot of their policies aren’t overly left; they just seem fair.”

“They’re bringing to the forefront the largest issue of our generation, which is climate change,” Shaun adds. He still believes that Labour is “the party that will deliver change”, but his constituency is in a safe Labour seat, so he feels able to vote Green to keep the issues he cares about at the forefront. “In my mind, Green is a pressure party, which is incredibly important and effective to have. Look at how successful right-wing parties like BNP and UKIP were in tabling their issues and edging the population in that direction.”

Voters placing their bets somewhere new is one thing, but whether trust in the current system can be rebuilt is another. “I think one of the few ways to make politics more trustworthy is some form of regulation,” Isobel says. Labour have advocated for a ban on certain second jobs for MPs, with leader Keir Starmer arguing that it would help end “dodgy lobbying”, but the suggestion was shot down by Boris Johnson back in March. “At the moment it’s so easy for anyone in government to act in ways that would benefit certain industries, and then walk into a position at a company in that industry afterwards. What we have isn’t functioning as a system of governance, it’s just people setting up cosy jobs for themselves,” Isobel explains. “At the very least, there should be a certain amount of time that has to pass before a politician can go on to work in a sector like energy, finance, or journalism.”

“I think the best politicians have a strong set of values and don’t falter on those values,” Shaun says of what makes a “trustworthy” politician. “They take risks and show courage. [Labour MP for Coventry South] Zarah Sultana speaks truth to power on such a regular basis it’s incredible. The same goes for any MP standing side by side with striking workers, and MPs like Richard Burgon who speak with a passion, conviction and anger that matches the urgency of our political situation.”

Despite the bleak outlook within the corridors of power — or the jungle, as it were — Shaun hasn’t lost hope entirely. “I’m not one of those that has across-the-board distrust of politicians at all,” he says. “I have distrust in Labour’s leadership, but in a certain sector of the party I think I have more trust than ever.”

Taken from the February/March 2023 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online here. On UK newsstands from Thursday 19 January 2023.