Spitting innocence: the use and abuse of drill lyrics in court

For a large portion of white society, rap is associated with a “racist construction of Blackness: danger, threat, uncivil”. As a result, drill lyrics are currently being misused in courts of law to prosecute Black and Brown young people in the UK, as a recent case demonstrates

By Tara Joshi

On Bonfire Night 2020, 16-year-old aspiring rapper John Soyoye was murdered in the street by a group of young men.

On 1 July 2022, four of his friends, Harry Oni, Jeffrey Ojo, Gideon Kalumda and Brooklyn Jitobah were sentenced to 21 years’ imprisonment (20 for Jitobah), after they were found guilty of conspiracy to murder for planning revenge attacks for Soyoye’s death. Three of them were present during different, separate incidents of harm — a non-violent chase, and two separate incidents where a machete was used, one of which resulted in somebody being hit by a car (the exact people who perpetrated this violence was never established). There were no fatalities.

Another six of Soyoye’s friends were also sentenced for eight years after being found guilty of conspiracy to cause grievous bodily harm. In the weeks before the day of sentencing, a protest march took place in Manchester against how the case has been handled by the court.

Despite not having any weapons, taking part in any violence or efforts to locate attack targets, four of the six other defendants were seemingly condemned solely for comments they made in a group chat with the other defendants three days after Soyoye’s death.

The boys were defined — and therefore condemned — by the prosecution as being part of the M40 ‘gang’, although they denied this. The defendants told the court that M40 is not a gang, but a drill music collective in which some, but not all, of them rapped. The quoting of drill lyrics in their chat, showing their shared love of UK drill — one of the most popular genres in the country — was also seen to be incriminating. (It should be remembered that even Ed Sheeran has released a UK drill song.)

Sentencing, Mr Justice Goose said: “It was played out in social media and through drill rap music, with threats of violence, the display of weapons, including firearms, machetes and crossbows.”

Typically, such cases are tried under joint enterprise laws: conviction and sentencing by association if it’s judged that the person had foreseen the associate might commit it. There is research that posits joint enterprise rulings disproportionately affect people of colour: most specifically, young Black and mixed-race men. (And according to a 2021 report from the Prison Reform Trust, more than a quarter — 27 per cent — of the prison population in England and Wales are from a minority ethnic group, in spite of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people making up just 14 per cent of the general UK population.)

Part of the reason for this is because joint enterprise encourages the deeply racist and classist assumption that groups of young, working-class Black men must be ‘gangs’, stripped of their individual experiences and humanity. In this particular case, the conspiracy charge rather than joint enterprise suggests that each of the individuals charged had a principal role — but a lot of the ‘evidence’ seems to show that some of this group of young Black boys have been sent to jail simply for who they knew and the music they liked.

As Roxy Legane from the platform Kids of Colour, who was present at the trial, explains to Rolling Stone UK, “Your choice to rap is a choice to be involved in a culture that is for many understood as ‘criminal’. As groups of young Black boys demonstrate their musical talent in videos, the prosecution know full well that many won’t be able to see past the ‘gang’ label, as what is presented to us as ‘gangs’ in mainstream media so often (unjustly) mirrors what we may see across musical platforms: the prosecution takes advantage of racism to do more racism.”

“Anything at all perceived as confirming violent behaviour can be removed from context and taken as diaristic proof of reality by the courts”

And so, as the violent and nihilistic UK drill genre rises to the fore, with many marginalised young people using it as a means of self-expression, criminalisation by association with the music is on the up. People could even just be quoting lyrics in a text message; using slang on Snapchat (in the Manchester case, one of the defendants having said “Gang shit!” was taken as ‘proof’ he was in a gang); have old phone photographs with friends doing ‘gang signs’ for clout; writing potential lines for new songs on their phone notes. No matter how tenuous it might seem to claim that teenagers liking UK drill confirms they are criminals, anything at all perceived as confirming violent behaviour can be removed from its context and taken as diaristic proof of reality by the courts.

Of course, the policing of Black music in Britain is nothing new. It spans back through jazz clubs, rock’n’roll, Notting Hill Carnival, jungle, UK garage, grime and the notorious Form 696 (a ‘risk assessment’ form through which the Metropolitan Police insisted that event promoters make note of the genres they would be playing and the ethnicity of their clientele, which was eventually scrapped in 2017).

But in the past few years we have seen an unprecedented level of censorship when it comes to UK drill. Earlier this year, VICE reported that YouTube had been working with the Met Police to remove drill videos from the site, complying with around 97 per cent of the force’s removal requests.

Back in 2019, Skengdo and AM were given a suspended prison sentence for performing their song ‘Attempted 1.0’, the first time in British history that performing a song had led to a prison sentence. Meanwhile, Digga D is subject to a Criminal Behaviour Order that states he must notify the Met Police within 24 hours if he plans to publicly release new music, so that they can screen the songs. Breaching this will result in an instant recall to jail, and it’s being enforced until 2025.

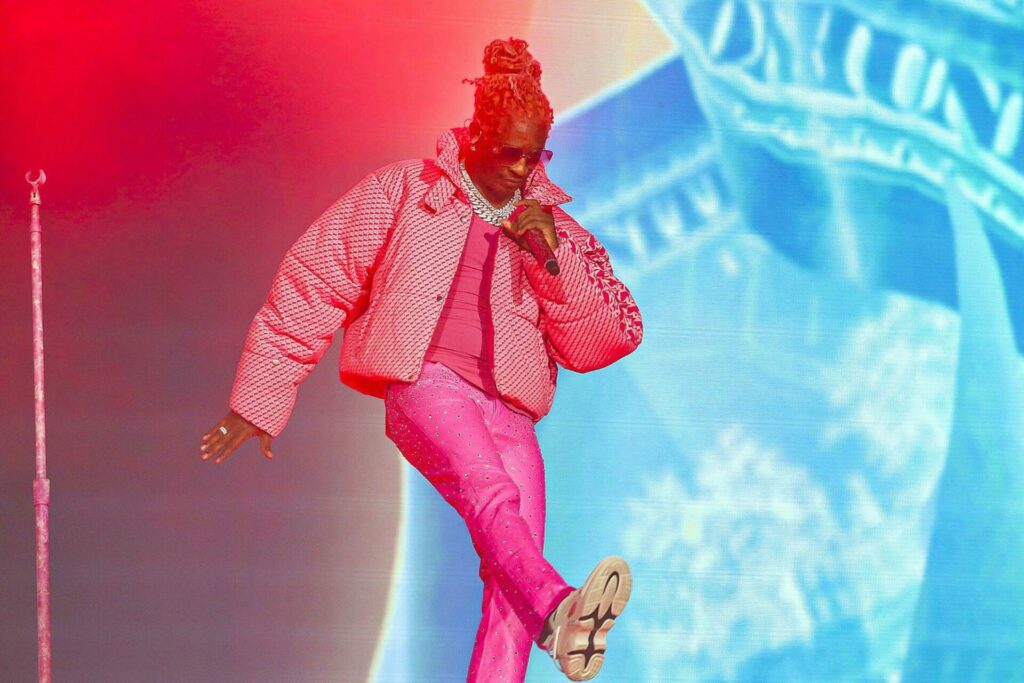

It’s a similar story in the United States. Young Thug and Gunna were recently arrested and charged under the state of Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, with lyrics and social media posts from members of YSL (the label and collective who the authorities are framing as “a criminal street gang”) being used as proof of conspiracy.

Legane explains, “I think rap lyrics can be misused first and foremost because rap is so specifically representative of Black culture, art forms and creative expression. For many, that association connects us to rap’s brilliance and the incredible Black artists and groups across the globe, but for a large portion of white society, rap is associated with a racist construction of Blackness: danger, threat, uncivil. Quickly, simply by rapping, you become those things in a court.”

Dr Alex de Lacey, a lecturer in music at Goldsmiths University, agrees. Speaking to Rolling Stone UK, he says: “One thing I always come back to is the way in which Black creative practice gets successfully policed — this idea that artists can’t embody personas, they aren’t afforded the realms to take on characters or role play. Everything they do is taken as verbatim, or indicative of some sort of criminality, which is just excessively racist.”

“For a large portion of white society, rap is associated with a racist construction of Blackness: danger, threat, uncivil. Quickly, simply by rapping, you become those things in a court”

— Roxy Legane, Kids of Colour

For Eithne Quinn, professor of cultural studies at the University of Manchester, it’s a complex genre to compare to any other. There are relatively few styles of music with lyrics that are in the first-person and so violent, but for the most part this is posturing. It’s a nuanced distinction because, of course, there is real-life violence and trauma happening that some of these young people are witnessing, not least after well over a decade of Tory austerity and institutional neglect.

As Quinn says: “The music content is certainly often violent, as is lots of young people’s popular culture. The lyrics are part of our violent entertainment culture. And they can sometimes also be a way of narrativising trauma for young people who have seen, or heard about, harm take place. If there’s been a violent incident in your town or city, then that’s shocking and newsworthy, and quite understandably young artists fold that in. But of course, it doesn’t normally mean they have anything to do with that harm.

“Rap is a complex art form,” Quinn continues. “These young people are rapping to entertain themselves and each other, as well as to develop their voice and artistry, and they’re often customising and repeating the rap phrases of others who they admire. They’re folding in exciting, everyday and sometimes traumatic experiences, as well as developing a sound that speaks to precarity, inequality and racism.”

It’s a difficult reality that also ties in with commercial success — as gangsta rap made clear back in the 90s, violent lyrics can help artists gain further fame and notoriety. Indeed, de Lacey also points to the work of academic Jabari Evans pertaining to Chicago drill: “He writes about digital clout, and the marketising of criminality — basically, rappers saying, ‘If you’re going to stereotype me, we’re gonna embrace the stereotype and therefore make loads of money out of it and say: ‘Fuck you’ to the establishment.’”

In cases such as the Manchester conviction, there is little courtroom understanding of the music (at one point, a prosecutor mistook references to Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur in a text message as being about Manchester gang members).

For the past 14 years, Quinn has acted as an independent expert in UK legal cases in which the prosecution seeks to rely on defendants’ rap music. She is very concerned about how the state is targeting groups of young Black people and using their art to convict them. She helped set up Prosecuting Rap UK to raise awareness about this and says there is a growing number of independent rap experts who can scrutinise the claims made by the prosecution about the music.

“What really shocked me was that in most cases in which rap was used, no independent expert was called; just a police officer offering interpretations to the courtroom of the lyrics, which, in my view, is a stitch-up,” Quinn says. “It’s really unregulated and unfair — procedurally, it’s racist. The police experts are neither impartial nor are they often fully knowledgeable.”

“What really shocked me was that in most cases in which rap was used, no independent expert was called; just a police officer offering interpretations to the courtroom of the lyrics”

— Eithne Quinn, professor of cultural studies at the University of Manchester

Quinn adds that in most cases rap lyrics and videos should have no place in the courtroom as they are too prejudicial and misleading — especially in group prosecutions that are increasingly the norm. She wants to see rap music kicked out of courtrooms; in the meantime, she says it is crucial that we question the legitimacy of using police as experts on rap and digital youth culture and support defence teams to mount strong challenges to the inclusion of this inflammatory material.

Legane noticed that it wasn’t just the prosecution and the police framing drill in a specific light at the Manchester trial. “There was little done by defence to challenge the racist construction of drill in the courtroom, and often the approach focused on instead trying to distance clients from the genre,” she says. “Frequently, even defence teams problematised drill, frequently sharing opinion to the jury that they agreed it was a horrific art form, why would anyone want to be involved in drill and its violence. Those thoughts were projected onto the jury in statements such as ‘You might think drill is an utterly appalling form of music.’ So when many — not all — defence teams fail to stand up for the genre and challenge the racism instead of the music, the prosecution has support.”

She continues, “The prosecution frequently made lyrics seem as if they were really relevant, when they were in fact repeated or similar lyrics to many drill tracks. The violent themes and imagery shared in these specific songs and videos, were pitched as unique, when they are not. And some choosing to rap about events of harm they had heard about were used to infer guilt, and to suggest potential presence at events that the prosecution had failed to prove physical presence for. While the jury was told to ignore lyrics that were to do with hearsay, they were already spoken in the courtroom — what has been heard cannot be unheard.”

In New York, a bill has just passed in the State Senate that seeks to limit the use of rap lyrics as admissible evidence in courts. Here in the UK, the Crown Prosecution Service is currently reviewing the use of drill lyrics in criminal cases. But even if the rules change, it would likely still be too late for those ten young Black boys in Manchester, and many others like them. At the time of writing, there has been no institutional support, in spite of calls to Andy Burnham, the Mayor of Greater Manchester, to step in.

The vilification of drill is a further symptom of this country’s institutional racism and classism. As Dr Lambros Fatsis, senior lecturer in criminology at the University of Brighton, suggested in his Policing the beats paper, policing UK drill helps the state to exclude those who it deems undesirable or undeserving of its protection, with even supposedly ‘progressive’ powers turning their heads.

“Policing UK drill helps the state to exclude those who it deems undesirable or undeserving of its protection”

If we consider another case in Manchester, the reality becomes clear. In 2019, teenager Yousef Makki was fatally stabbed in the heart by his friend, the-then 17-year-old Joshua Molnar. It took place during a drug deal. Molnar’s lawyer described him as living a juvenile fantasy life of a ‘middle-class gangster’; there were photos and videos of Molnar posing with knives — and he was, of course, a big fan of UK drill. But Molnar was found not guilty of murder or manslaughter and was acquitted on the grounds of self-defence. He was given a 16-month detention and training order in a young offenders’ institution for possession of a knife in a public place and perverting the course of justice by lying to police at the scene. Seven months later, he was free.

The difference between the cases, perhaps, is that Molnar is privately educated and white.

Taken from the August/September 2022 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Buy it online here.