Why Fascism Is On the Rise: Ash Sarkar In Conversation with Paul Mason

In his new book How To Stop Fascism: History, Ideology, Resistance, writer Paul Mason outlines why and how white extremism is gaining support in the UK

By Ash Sarkar & Paul Mason

It’s easy to see how Whitechapel, with its well-established Bengali community, dual-language street signs and 7,000-seat mosque, looms large in the fevered imaginations of fascists. Women in niqabs amble along the high street hauling overstuffed plastic bags; Deliveroo riders, that underpaid tribe of many nations, zip from pickup to pickup. This part of London has been the target of tabloid hysteria, and far-right attacks.

Lurid (and debunked) claims of Sharia enforcement and anti-white assaults have long dogged the area. The English Defence League, following in the footsteps of Oswald Mosley 76 years earlier, attempted to march through the neighbourhood in rejection of its diversity. But if Tower Hamlets has truly turned into an Islamic no-go zone, somebody’s neglected to tell the neighbourhood’s ubiquitous hipsters and property developers that it’s not safe for white folk “round these parts”.

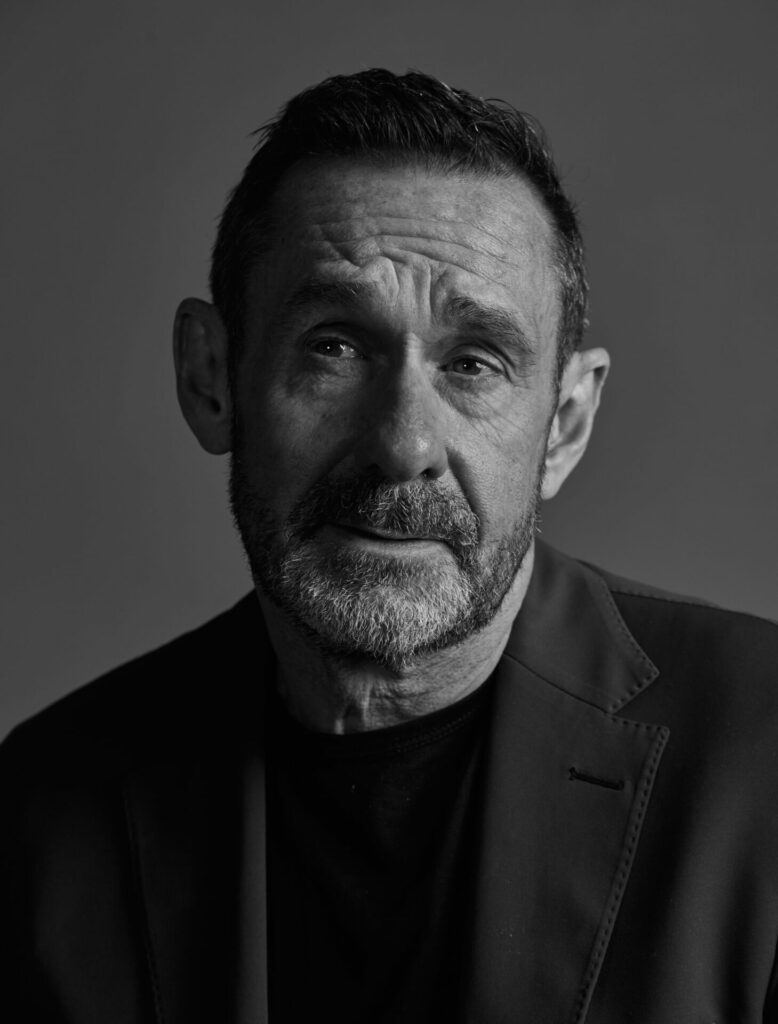

I’m here to talk to journalist and author Paul Mason about his new book, How To Stop Fascism. He started life as a jobbing journo, working his way up to become Newsnight’s Business Editor in 2001. By the time I first met him, as a student activist radicalised by austerity and tuition fees, Mason had freed himself of the impartiality constraints demanded by public service broadcasting to become a full-time thought leader for the left.

His 2012 book, Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions, was a bible for those of us seeking to recreate Tahrir Square outside of Parliament. We worked closely together as the Corbyn movement gave us the tantalising glimpse of achieving socialism in our lifetime. Now, just across the road from where a 25-year-old Bangladeshi man named Altab Ali was murdered in a racist attack in 1978, Paul Mason wants to explain why the most pressing task for the left and progressives is to defeat modern fascism.

The thing that I really liked about not just this book, but I think it’s how you think, is that you tend to write and think in map-making exercises. You tend to go, “Well, this is the lay of the land,” and then you sequence it afterwards. It seems to me to be a very cartographical exercise. Where do you see fascism making a comeback? What was the first pin on the map for you?

The first pin on the map was Whitehall during the prorogation crisis. It was this pro-Brexit demo called by Tommy Robinson supporters. I was on the platform of a really peaceful remainer demo. They didn’t know what to do when 200 kind of tough-looking, quite elderly boneheads turned up and disrupted it.

These people were shouting at us, poking me in the chest. I didn’t realise until halfway through, because we were filming them, that what they were shouting was “Paul Mason, Marxist. We’ve researched you, you’re a traitor to our country.” And then they started going on about Marxism, and I just had this flash of realisation: something’s changed. Thirty years ago, when people like that came to places like Brick Lane, where we’re speaking, they didn’t like the way immigrants dressed, they didn’t like how migrants’ food smelled. They thought, “These people take our jobs.”

They weren’t worried about Theodor Adorno or Walter Benjamin, and now they are. That’s the moment I realised that Trump is not the worst it’s going to get. It’s the followers of these essentially right-wing populist movements that are radicalized, and they’ve adopted a theory. Nigel Farage, Matteo Salvini and Trump are not theorists. But their followers now have a theory, and – essentially – it’s fascism. As a Marxist, you inherit the baggage of the Marxist theory of fascism, which, I argue in the book, is flawed. I was thinking, “What could possibly explain why someone with an England football British bulldog neck tattoo, is suddenly worried about Walter Benjamin?” So I started researching them.

You call fascism a recurrent symptom of system failure unto capitalism. What is it that’s happened to our democratic institutions over the past decade? What’s made them vulnerable?

The recurrence is the important thing. The world I grew up in as a kid in the ’60s, the assumption was that fascism was a one-off; it had been defeated. But something deeper happened in the 1930s and is happening now: a system fell apart. Today, the system that’s fallen apart is not just the economy that crashed in 2008. The inner logic of free market capitalism fell apart, at the moment when the state saved the market, with Lehman Brothers.

Neoliberalism was a kind of holistic world view. It explained everything: who you were going to marry, what your job was going to be, why you lived in a certain place. The market had decided all these things. When the free market economy collapsed, what I think we’ve been watching, is there’s been a slow decomposition of this holistic world view.

No matter how hard you try, as a historian looking at historic fascism, you’re looking through a series of lenses. No matter how hard you try, the one thing you can never experience or touch is the mass psychology: how it felt to be in those movements.

But if you go and look at what writers, sociologists, philosophers at the time were describing, they realised that something had clicked in people’s heads on a mass scale. Seeing it now – how people go from anti-vax to QAnon to anti-5G, to believing that Trump won the election – it’s clear that that’s how Nazism must have come together in the minds of its adherents. But we didn’t realise that.

You talked about the importance of myth-making and identifying myth as a story which you can make come true through the ferocity of your belief. Do you think these people want to believe that they’re the heroic centrepiece of a story, battling against some grand evil? And it’s something which gives their lives meaning in an otherwise meaningless world.

Let’s remember, what robbed their lives of meaning is neoliberalism. It’s my generation, the late boomers. My dad, who was 11 when the war started, 18 when he went down the pit towards the end of the war, had a fantastic life after the war because capitalism delivered for him. Thatcherism came in, smashed the social conditions of his existence up, smashed up the world in which I grew up. People are looking for an equally powerful single explanation of the world that gives them agency – and that’s the source of fascism’s current allure.

Some would say that fascism offers an explanation for and solution to loneliness; that struck me when you were talking about your dad. Someone who’s part of black pill culture and the incel side of things might think: “Well, that’s because he was able to find a woman, marry her, have kids. There were no divorces.” To what extent do male fantasies of potency factor into this?

One of the things we must get our heads around about modern fascism, is that racism is no longer the single gateway into it. In the book, I argue that violent misogyny is the co-equal gateway, and that’s because of 50 years of reproductive technological shock: women are gaining control over their reproductive capacities, and in many cases, winning equal rights. Hitler and Mussolini were misogynists: Mussolini drove women out of certain jobs; Hitler gave medals to women who had five babies, and sterilized others who were considered subhuman. But they weren’t facing a substantially sexually and economically liberated generation of women.

If you want to reverse modernity, reverse to a world of ethno-states, which is what modern fascism wants, then you must co-equally attack feminism. Then there’s the problem: most racists want to hit a Black person, but haven’t, and most racists say a migrant has stolen a job, but that’s actually not true. But every violent misogynist has hit a woman, and most of these incel misogynists have indeed seen their status usurped by women, both in the dating hierarchy and at work, where they may have a female boss. And so there’s a whole extra set of men angry about women, on top of white people angry about migrants.

Your book points out that what’s being called Marxism by the far right is actually just liberalism.

Their theory, and it’s borrowed from American conservatism, is that when the proletariat failed to destroy capitalism, a bunch of cultural Marxists decided to destroy Western society from within, by promoting feminism, equal rights for refugees and migrants and racial minorities, and transgender people, lesbians and gays. By destroying the traditional family.

And they ask themselves, “How come this woke stuff is so popular?” And the answer has to be, it’s all a plot by the cultural Marxists, and that the others are merely dupes and carriers. That’s why they see liberalism as a form of Marxism.

How do you think social media and WhatsApp and Signal has facilitated this kind of networked, and in some ways kind of stochastic fascism?

Stochastic is the best word for it, although every time I use it people go, “Well, what does that mean?”

What does it mean?

Stochastic in maths means something you can predict as probable but random. If Trump issues a video of himself body-slamming a wrestler, whose head is being wrapped in the logo of CNN – which is a joking way of saying, “Let’s kill CNN” – then he doesn’t have to issue an order to somebody to send a pipe bomb to CNN, although somebody does. And then when the bomber is on trial and he claims that Trump inspired him, of course nothing happens to Trump. It’s the same way as Bin Laden saying, “It would be a good idea if people attack the West.” It’s not directly traceable as an order.

The stochastic nature of both terrorism and fascism is a product of a move to a networked society. But there are other equally challenging new aspects to fascism. One is that you can co-create your own fascism. Hannah Arendt made it absolutely clear when she said, for fascists, the moment comes when they no longer need to believe their eyes and ears. All they need to believe is their imagination. And the imagination can summon up a reality that makes total sense to them, even if it’s factually bullshit. The idea that Trump lost the election; that Hillary Clinton and Tom Hanks are part of a secret global network that sucks children’s blood. The QAnon conspiracy. That perfectly conforms to our understanding of what the Nazis were doing in the 1920s and early 1930s – creating a fantasy world that people believed.

What then happens is that people get drawn into performative self-deception, so everybody has to be demonstrably and publicly believing this bullshit. They don’t just sit there any more in their basements going, “Yeah, maybe the world is run by lizards.” No, you have to be out there with a T-shirt with a lizard on it, showing others that you are just as bought into this cult bullshit as they are. It’s accelerating the speed at which people adopt this performative self-deception lifestyle, and QAnon was a great example.

I want to return to gender, because to me there seems to be this crossover between influencer culture and far-right digital strategy. Talk to me about the role of young, conventionally attractive women in the fascist digital ecology.

There’s one obvious thing, and that is on your extremes of the far right, there’s something called the Trad Wives movement. They want to live a traditional female lifestyle, as the servant of a man. Again, because we’re always drawing historical parallels, this is what Hitler’s SS was all about.

Many women ultimately realise that they are just there as adornments for what is essentially a male power movement. The essence of fascism is a focus on nature, war and nation, as opposed to the left’s focus on history, revolution and class. And if fidelity to nature is the central idea of fascism, then the idea of women being pre-determinedly submissive to men, through their evolutionary psychology, is central to the fascist ideology today. It wasn’t a surprise that certain people who think of themselves as essentially white, are drawn to white supremacy. More than years into the modern women’s liberation struggle, unfortunately there’s going to be female fascism.

How much can age explain the authoritarian right in this country in particular with Brexit? But potentially also the United States. Polling shows that strongest support comes from older voters, retirees, homeowners. Is this the last sting of the baby boomers, the most privileged generation in history, catching a glimpse of their own mortality and turning to a supremacist ideology?

There’s a common argument on the left that it’s because retired people have mortgages, and buy-to-lets, and they’re rent seekers rather than workers. But they have been workers. If “being determines consciousness”, a switch between being a foreman on a building site to a retired foreman with a house and pension is not going to make you immediately turn fascist. I think we have to look deeper than age and deeper than economic function. I’m part of that generation. I’m 61. Our generation were told: we know who we are, where we come from, and where we’re going. And then neoliberalism shattered that world and they had to take a decision of whether or not they were going to be nostalgic.

Some people from that generation end up hating everything about the modern world to the core, from neoliberalism to racial diversity to feminism, to the fact that they don’t have much sex or any sex at all. They end up authoritarian, they barely tolerate democracy, they’re assholes, they’re racists. But in general, they’re not fascists.

The problem is, however, that as they radicalise, many are adopting theories that are quite clearly fascist in origin. They may have started with a spontaneous utopian vision, of going back to the days of Harold Wilson and Ted Heath: full employment, free school milk, all-white settled communities. But fascism is leading them from that to the idea of an ethnic revolution: “We’re going to take our country back.”

Meanwhile, among young white men, violent anti-feminism is finding its way into the discourse. If you’re a white supremacist and you’ve convinced yourself that you are about to be genocided by migrants that’s a strong impetus towards violence, it explains why one in six of all terrorist prisoners in Britain are white supremacists, far right.

I think the number one message I want to get over in this book is, yes, Tommy Robinson has been banned from Facebook. Yes, Trump is gone. But much worse people than Trump stand ready to take over and the ideology they’re peddling is persuasive and coherent, even if completely severed from reality.

We’ve only got a couple of minutes left, but I suppose the final question is the biggie. Which is: If all of this is the diagnosis, what’s the prescription?

If you look at it historically, stopping fascism is actually very simple. The only thing that ever defeated fascism in real time, apart from Red Army tanks, which we don’t have any more, was an alliance of the centre and the left. And that’s really distasteful to both the modern centre and the modern left, but it has to happen. Above all because of climate change. We can’t let this alliance of fascism and right-wing populism sabotage the decarbonisation of the economy, so we have to form alliances that keep them out of power until climate change is sorted.

The second thing, and probably one of the most controversial things I argue in the book, is we just need law enforcement to enforce the law. In America, there’s a ‘defund the police’ movement. I don’t share that goal and I don’t think that applies to the UK, either. What we have to do is force the state machine to recognise that we employ them to defend something called a democracy. There need to be specific laws against fascism, and regulations on big tech to stop them spreading fascist ideology.

There have been far-right terrorists found within the British armed forces, but unfortunately one of the armed forces that was really attracting far-right extremists is the German army. They have discovered entire units that were heavily penetrated by the far right. So, as advocated by democrats in the 1930s, you have to police the police and armed forces to weed out fascist infiltrators.

Third, we need to consciously foster an anti-fascist ethos. It’s one thing to say Kick Racism out of Football, another to say Kick Fascism out of civil society. But that’s what we need. Trump tried to criminalise antifa: we need to defend the concept of antifascism by making it mainstream. We need to be vigilant.

An extended version of this interview is printed in Issue 1 of Rolling Stone UK, out now.