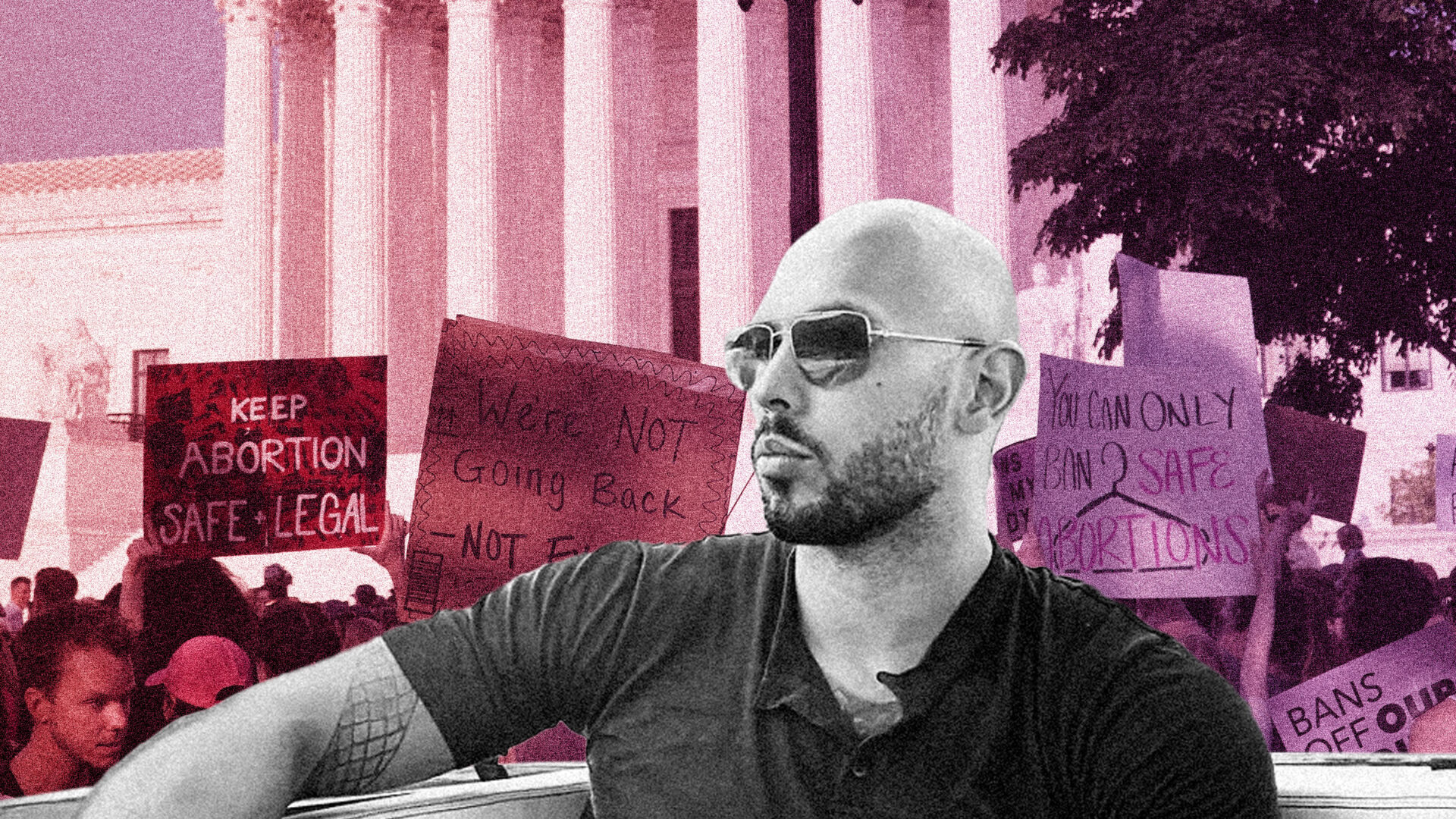

2022: the year that misogyny was back in fashion

Despite the so-called breakthroughs in women’s rights following #MeToo, it seems like everywhere you look these days there’s a dude with a crap beard and a six-figure net worth ranting about the ‘war on men’.

By Emma Garland

This time last year, very few people thought about Andrew Tate with any regularity — if at all. Now, he’s inescapable. The former kickboxer and failed Big Brother contestant from Luton went from relative obscurity to a pound-shop Joe Rogan over the summer, trafficking primarily in extreme misogyny and get-rich-quick schemes aimed at young men. Following an influencer marketing model (membership to his online platform, Hustlers University, costs £39 per month), with an image along the lines of Kendall Roy via Dr. Evil, Tate shows up most often in viral videos, chuffing on a fat cigar while monologuing about how “females” belong in the home. His rise was rapid, but not unexpected.

Before he was permanently banned from the platform in August, TikTok videos under the Andrew Tate hashtag had more than 13 billion views. He also had millions of followers across Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and Facebook. The Observer reported that, in the month of July, there were more Google searches for his name than for Donald Trump. These numbers were partly boosted by copycat accounts designed to game the algorithm, plus a healthy share of detractors dunking on his engagement bait — “I can emotionally affect [my haters],” Tate admitted himself in one video. “All I have to do is go on the internet and say something obvious like women can’t drive […] And they have a mental breakdown.” However, he also has a large, dedicated fanbase that speaks to a wider cultural trend towards misogyny.

In March, the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership and the market research firm Ipsos conducted a survey on gender equality in 30 countries. The results show that a third of men think that feminism does more harm than good, and that traditional masculinity is under threat. This supports previous research by the charity HOPE not hate, which found that 50 per cent of young men in the UK believe that feminism has “gone too far”. This is despite evidence that gender inequality has actually increased globally since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic due to

its disproportionate impact on women.

In the UK, there has been a surge in domestic violence. Between April 2020 and February 2021, calls and contacts logged on Refuge’s National Domestic Abuse Helpline (NDAH) went up by an average of 61 per cent. Meanwhile, spending on domestic violence refuges has been cut by nearly a quarter since 2010. Continued austerity, tax changes and benefits cuts have also thrust a greater number of women into homelessness and poverty, with the escalating cost of living crisis spelling more precariousness to come.

“It seems like everywhere you look these days there’s a dude with a crap beard and a six-figure net worth ranting about the ‘war on men’”

In September, Refuge called on the government and the then Prime Minister Liz Truss for help. Among their demands were raising Universal Credit in line with inflation and exempting survivors of domestic abuse from the benefit cap. So far, no such measures have been forthcoming.

Zoom out and the picture is similar around the world. Following the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, restrictions on women’s movements, bodies and education have mounted steadily. In the US, the overturning of Roe v. Wade this summer has led to at least 14 states imposing abortion bans. And, most recently, women in Iran have been at the forefront of escalating protests sparked by the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was detained for breaking hijab laws. Femicide rates are on the rise globally.

Politically and culturally, the landscape is sinister. Pop feminism dominated Western societies throughout the 2010s, paving the way for high-profile — often celebrity-focused — movements such as #MeToo and Time’s Up. Meanwhile, women in general were becoming worse off. Even so, the dial of public opinion has swung the other way in response. Tate is a small figure in a vast online economy that also includes grifters like Dan Bilzerian, Jordan Peterson and Roosh Valizadeh, whose rhetoric about what men deserve appeals to those who feel uneasy in the face of social change and economic downturn. It seems like everywhere you look these days there’s a dude with a crap beard and a six-figure net worth ranting about the “war on men”. In reality, though, they’re bottom feeders in the world’s lurch towards the far-right.

Taken from the December/January 2023 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Read the rest of our essays reviewing 2022 here.