By the Light of Day: how ‘daytimers’ created space for a South Asian club scene

Rolling Stone UK hears from the former 'daytimer' regulars about the secretive music events that formed a seminal era in British South Asian culture

By Tara Joshi

There’s a longstanding stereotype that South Asian parents are strict about their offspring going out and partying. Such fixed ideas are often rooted in truth and, for the teenage British children of first-generation immigrants originally from South Asia (predominantly Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis), going out on a Friday night like their white peers was often out of the question. It might bring shame to the family, not to mention encroach on study time, parents believed. But it wasn’t just about family — overt racism was rife in the UK, and there are countless stories of bouncers who simply wouldn’t let Brown faces into their nightclubs back in the 80s and 90s.

And so, South Asian youth took it upon themselves to make their own spaces. This was the era of ‘daytimers’, covert events that took place during the day — including schooldays — so that teens could go and party with their peers without their families finding out. Another factor was that many clubs didn’t want to run Asian events in the evening. Some were small gigs in sweaty club basements, while others were on a larger scale — coachloads of people from around the country would head to venues including London’s Leicester Square Empire, The Hummingbird in Birmingham and Maestro’s in Bradford.

Panjabis represent the largest demographic among British Asians and, as early as the 70s, Panjabi folk music met with Western technology to create the flourishing UK Bhangra scene. Daytimers provided fertile ground for UK Bhangra to thrive and fuse with (mainly) Black British music, with live bands and DJs giving second-generation South Asians a sound that seemed to represent the new world they occupied.

Out of necessity, these were secretive events, and cultural stigmas mean that even now many people who attended still aren’t comfortable speaking openly — particularly women. Whatever the circumstances, these were formative experiences that shaped who they became. Rolling Stone UK spoke to former daytimer regulars to learn more about this seminal era in British South Asian culture.

Rav Patti (producer, DJ, broadcaster, Panjabi Hit Squad): When the scene started off, I was really young. The generation that was maybe two generations above me needed daytimers because they couldn’t get into any nightclubs. Racism in the 70s, 80s and 90s was a lot, so that’s why some of the first daytimers were in pubs in, like, Southall [a west London area known for being a South Asian hub], in the small halls at the back.

Ritu (DJ, broadcaster, promoter): Asian promoters were not given the option of a ‘nighttimer’. Venues didn’t want Asian promoters running clubs at nighttime in their venues. So part of the emergence of daytimers was a race bar, a colour bar. Maybe venue owners also had it in their heads that the Asian market wasn’t something they could earn much money from [under the assumption that Asians didn’t drink].

Ajay Srivastav (musician, writer): We talk about daytimers as a series of events, but I’d argue that daytimers is a lifestyle, a lifestyle that I carried on through my life, even now — a lifestyle of duplicity. As British Asians, there are things you would never tell your parents, not only for fear of judgement or reprisal, but just [because] they wouldn’t understand. There were parts of your life you’d keep secret.

Bobby Friction (DJ, broadcaster): We kept it secret because people were supposed to be at college; we were supposed to be at school. Parents in those days were pretty much all first generation; most of them had only been in the country 15 years max. We could never tell them we were going to a club, they’d have stopped us. Even I kept it secret, and I probably had the most liberal parents in all of west London.

Ajay: I still haven’t told my mum and dad. I’ve spoken to former promoters for the play [the forthcoming Back in the Daytimer, co-written with his wife], and they’re still hesitant to talk about it because of the reprisal from other community people.

Rani Kaur (DJ Radical Sista, community activist): I’m a bit different, because there was no secrecy with me. Wednesday afternoon was PSE [personal social education] in Huddersfield. There were no actual lessons you were missing, so daytimers thrived here on Wednesday afternoon. In Bradford, they had no lessons on a Friday afternoon, so that’s when daytimers thrived there. Daytimers often existed within their local set-ups, so people didn’t necessarily skive lessons, they [fell on the days they] didn’t have lessons — but they wouldn’t tell their parents that’s where they were going instead. But when I was DJ’ing, I’d literally just say, “Mum, I’ve got a gig.” When I started, Mum was really concerned, but then she saw me play and she was literally like, “Oh, that’s all you’re doing?” All I was doing was playing music. My chacha [paternal uncle] would even drive me to my shows.

Ajay: I grew up in a really white area in north London in the 80s, went to a really white school. I had a mate, Deepak, who was the only other Brown face in my year at school. And he would know when daytimers were happening. It was always short notice: “We’re going tomorrow,” or, “Next week, we’re gonna bunk off.”

Bobby: I was 16, it was the 80s, and it was easier ’cos I was bunking off college, not school. I remember we were so excited for our first daytimer.

Ajay: At the time I didn’t know how we all found out about them; this was before mobile phones, before the internet. In the years since, from researching, I’ve discovered there were some flyers obviously, but mainly it was an underground network, selling tickets through school kids — especially in the early days. It was probably different in the 90s, but back then nobody knew [about daytimers], unless you knew. They didn’t want to make a big deal of it and attract parents or teachers.

Rav: When you’d go to your local fast-food restaurant, the music shop, the corner shop, the flyers would be there. I think they were very careful about not promoting in schools —but you’d have posters outside schools, which they couldn’t do much about. There’d be ticket agents at schools as well, getting a commission for selling tickets. I did that later on, too.

Bobby: The first time, me and the boys got dressed up, got on the Tube, and we went into town. We were doing that 16-year-old drinking, you know? Drunk but not sloshy, full of life. We turned up in Leicester Square, hung out there for a while. I’d never been to a nightclub before that, so we were practising stories in case we got questioned, but there was none of that, they just let us in. It was very obvious that the Empire was like, “Just let all the Asians in.” When I first walked in, I felt elation. It looked like the inside of Top of the Pops: massive disco lights, lots of neon, the first time you’re ever hearing amplified music like that, so it’s shattering your ribcage. But the main thing that hit us was that we’d never seen that many Brown faces outside of weddings. And these were all young Asians — everyone was probably 16 to 25. It just blew me to fucking pieces.

Rav: It was like a film. You’d wake up, get dressed up, meet your friends, get a bus to whichever venue you were going to and grab some breakfast on the way. Queue up for 11am, whether it was rain, snow, hail, whatever. My first one was at this club called Zenith in Park Royal, [west London], it was an under-18s daytimer. This whole event would be the most amazing event you’d ever, ever been to, and they’d happen every six weeks or so. The word would spread quite fast that there was another event going on, and you’d know weeks in advance so you could save up to get clothes for this one event.

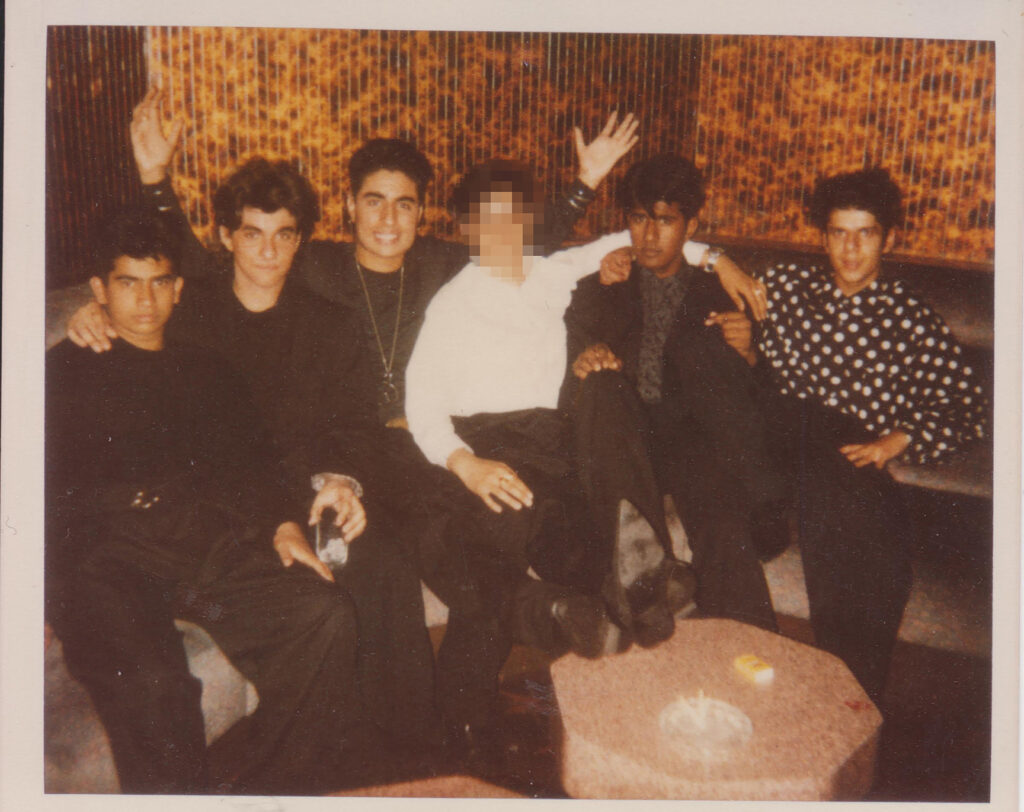

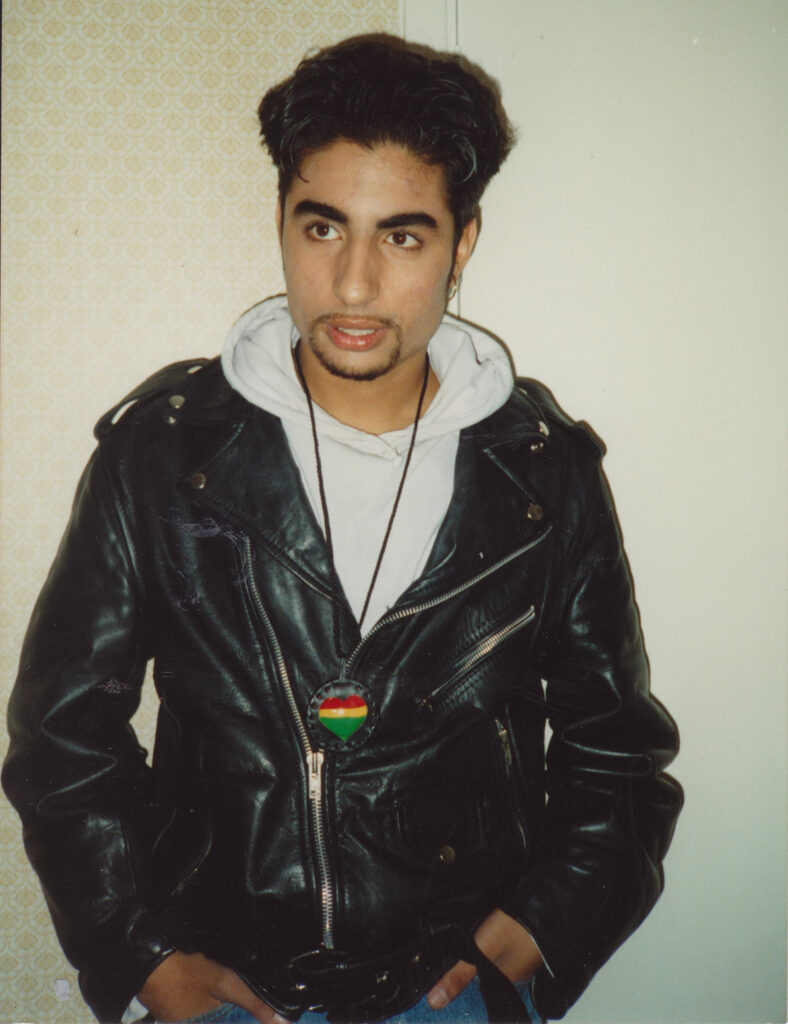

Ajay: Luckily, my secondary school was in Hammersmith, around the corner from Hammersmith Palais, so we’d walk. McDonalds was on the way; we’d get changed out of our school uniforms in the shopping centre. People definitely made an effort in terms of the look. It was kind of designer-y tracksuits, trainers, very hip-hop influenced.

Ritu: Baggy jeans, combat boots, baseball caps for the boys… The girls were mostly in little black dresses, looking sparkly and glittery. I had been DJ’ing since 1986, but I didn’t worry about what I was wearing playing places like Mambo Inn in Brixton. It was only at the British Asian events that I was more conscious of what I needed to look like. I was putting on extra makeup, that sort of thing.

Bobby: In the 80s, most of the girls had perms, lots of big hair, lots of hairspray. The lips were invariably blood red, and they wore short cropped jackets with salwar bottoms — it was like Mel and Kim on top, Panjabi girl on the bottom.

Ajay: It’s a shame there aren’t more pictures, but there wouldn’t be because of the issues of secrecy. And so the same pictures come up when you Google ‘daytimers’ — [Tim Smith’s photos of] the three girls, that guy leaning on the decks…

Tim Smith (photographer): I moved to Bradford in the mid-80s to work as a photographer. There weren’t that many people around with cameras in those days, and the life of the Asian communities in Bradford — as in most other towns and cities — was almost invisible in terms of the general mainstream media and to the outside world. I knew a lot of young Asian people, and [the parties were] very much a word-of-mouth thing, and they said, “You ought to go photograph one or two of these” — and so I did.

There were big civic concert halls where Bollywood playback singers or Indian Classical musicians would play, but they were all family-orientated — or even if you didn’t go with your family, there would be uncles and aunties around. This was the first time young people took it upon themselves to organise their own cultural spaces, allowing self-expression away from the prying eyes of parents, uncles and aunties. Often the girls would turn up to these dos in salwar kameez and they’d have a carrier bag with them and they’d slip into the loos, then they’d emerge looking like Olivia Newton-John —the bouffant hair, the shoulder pads, the white trouser suits.

Rani: I just went in the same clothes I left the house in, I never used to dress up.

Rav: I think in the 80s people turned up in their traditional clothes more if they were coming from home, because that’s how you dressed if you were leaving the house. But by the 90s, it was more streetwear than traditional attire. Levi jeans, Moschino shirts, all my friends used to wear MA-1 flight jackets in all different colours, and then Air Maxes.

Bobby: Maybe because of the age we were at, there was that real adrenaline of being a sexualised youth in a club with music, wrapped up in Brownness. There was a fairly even gender split.

Ritu: They were very intense, usually very male-dominated crowds. I have been to daytimers and other Bhangra gigs where it was probably not the best place to be in if you were a small woman and feeling a little bit vulnerable or not comfortable in crowds. Ultimately, as girls, there were less of us who would have rebelled as teenagers and taken the risk of going off to something like a daytimer before we’d left our parents’ home to go to uni or wherever.

Rani: I always made sure that wherever I was, the gig was safe. Sometimes people would feel wary about going, but a lot of women knew if I was DJ’ing they’d have no trouble. I took a lot of crap from some people that were unhappy about Asian women DJ’ing and bringing Asian women to gigs, but I just kind of fobbed them off.

Ritu: I was always really nervous before going to play any of the events on the British Asian Bhangra scene. I knew that, invariably, I would be the only woman in the DJ booth. It’s not surprising there were so few of us, given we weren’t encouraged to go to clubs, to hang out with boys, to pursue music as a career.

Rani: I used to be a regular at daytimers, and I’d help out with the lights and tell them what songs were good to play, but I didn’t have any vinyl, and the shops in Huddersfield only had cassettes. But then I was in Leicester for a conference, and I went to this shop called Friends Electric, which had lots of Asian records. I must have spent hundreds. Next thing I knew I was on pirate radio playing Asian music, and then suddenly I was being asked to play the gigs.

Bobby: In 1986, the music was Bhangra — it wasn’t traditional Bhangra, it was UK Bhangra. When the live bands came on, you weren’t thinking about ‘fusion’ or even Bhangra, you just thought, ‘That’s Heera’ or ‘That’s Alaap.’

Rav: The live acts who had it on lock? Malkit Singh, who was already an established artist by my parents’ generation, but he was always popular. Jazzy B from Canada caused a storm ’cos he was the new boy on the block. B21, the boy band, who were new and young, one guy had a turban on and all the girls were loving him. If you had one of those acts on, you were guaranteed success as a daytimer promoter.

Bobby: The DJs in the 80s were playing predominantly Bhangra, but also the big R&B hits, occasional hip-hop tracks. By the time it got to 1990, I was at uni, and it was turning into a fusion — that Bombay Jungle [a seminal British Asian club night that ran from 1993 to 1995] sound. A DJ would come on and just play hip-hop, then a DJ would come on and just play Bhangra. But the gigs in the late 80s were definitely predominantly Bhangra.

Ritu: It wasn’t just hip-hop. We’d fuse Bhangra with ragga dubs, reggae dubs, sometimes house dubs — anything that was instrumental with a good strong bassline and a beat that could be synchronised with the dhol. I would have thrown in a lot more Bollywood if I could, but that’s not what those audiences wanted.

Rani: My stuff was Bhangra, because I love Bhangra. But I used to mix in whatever records I liked — Prince, jungle, house.

Rav: I now realise what the DJs were doing was groundbreaking, mixing two cultures together. By the 90s, they were mixing in jungle, drum’n’bass, and by the late 90s, when UK garage started coming up, that was getting mixed in. But also something interesting started to happen, and rather than just mixing and remixing pre-existing songs, producers were starting to make original tracks, and selling and playing their original music. That’s kind of how the Bhangra garage scene started.

Ajay: Everyone was there to listen to music, to meet people, to scope out the opposite sex. And we were all Brown. Looking back now, I see that was so liberating! It was the first time we all hung out together on our own, people with the same skin colour and the same vibe. The barriers were broken: Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, all hanging out with each other. Where else was that gonna happen? Not with our parents. But then again, there were definitely tensions and unwritten rules about who you’d speak to. One promoter I spoke to even said he banned all national flags.

Bobby: There was nearly always a tension between east and west London at the end of the party; I’m sure a couple of times fights started. And daytimers were very Panjabi-heavy, with a lot of Pakistanis there. No one ever talks about this stuff, but at the time, even though Bhangra is for everyone, we definitely had a sense of “What are all these Pakistanis doing here?!” You have to remember we’d come straight from our parents, who were born either just before or just after Partition, so their views towards Pakistanis weren’t aggressive or horrible, but just more like, “Who are these guys!?” And that affected us.

Ajay: In those days, our community — like every minority community — was so put upon that we had angst and aggression within us. You could feel it even walking along Southall Broadway. So there was always going to be tension at those parties, but I’d say the overriding thing was fun, and dancing, and doing what you wanted to do without your parents finding out.

Tim: I can’t remember seeing another white face in there… maybe the staff? But white people didn’t really know about daytimers. I remember doing a project down on Green Lane [London], and I saw a poster that just said “Ooh, aah, Dracula! Halloween daytimer” and a phone number. If you were a white person, you’d have no idea what that meant and you wouldn’t ring that number. I only knew about daytimers because my Asian friends told me. I think promoters didn’t particularly want the wrong people to find out — say, elders within the community. Once things started to leak out, parents weren’t very pleased about it. I’ve heard secondhand stories about announcements being made at the gurdwara [Sikh place of worship] that these things were happening and they weren’t good, because of boys and girls mixing.

Rani: I remember some local people in the community were upset because I was doing a daytimer, and it was gonna reflect badly on the Asian community. But I said, “Look, if they wanna come, they’re gonna come — all we’re gonna do is play music and dance.” I sometimes think that people had only seen nightclubs in Bollywood films, so they thought it was all girls in skimpy clothing dancing on pods…

Ajay: It never happened to me, but you’d hear stories of parents, teachers, religious leaders, community officials coming down and scoping kids from their schools or communities out and grabbing them. You’d hear about people getting busted at the local daytimers especially. But this added to the thing of the whole scene! Asian kids were actually doing something to upset their parents? That’s great! Finally. And even then, they were trying to keep it secret, which is why lots of people still won’t talk about it.

Tim: Alcohol was available, which was probably another worry, but I can’t remember seeing many people drinking. The guys I went with were serious about their religion and teetotal.

Rav: At Zenith there was a zero-alcohol policy downstairs, and you could only get drinks upstairs with an ID showing you were over 18, and you could only consume the drink in that area. But the majority of the people were just there for the music.

Bobby: People don’t really talk about the drinks and the drugs. You can’t talk about something like the second summer of love without mentioning ecstasy, but Asian musical manifestations in this country haven’t been driven by a singular drug, so we don’t talk about it. A lot of that was going on as well, though, I suppose we don’t talk about it because it wasn’t centre stage, and because of respectability in our communities still.

Ajay: There was definitely alcohol and people taking drugs, though I’m notorious for missing details like that. But this was back when you could still smoke inside, so we all must have stank of cigarettes when we got home — so I don’t know how we all got away with that one…

Bobby: You’d get on the Tube, someone would always have aftershave on them because we would stink of fags and booze. And more often than not, one or two people would be led to Jersey Gardens or a park somewhere in Hounslow to sober up before we went home.

Ajay: I do remember I used to have this tiny little aftershave. We were crafty, man!

Rav: We’d get KFC or McDonalds on the way home, and on the Monday after, everyone at school would talk about what happened. There was also all the car culture associated with it. You’d just got your licence so you could cruise up to and back from the daytimer in your mum’s Ford Escort XR3.

Tim: It was all a bit of an eye-opener. Walking through Bradford at 2pm on a Wednesday, into these dark basements with flashing lights and all this Bhangra stuff. The girls would go back to the loos and change again, and emerge back on the streets, like they’d been in the college library for the afternoon. It makes me smile thinking about it now, really.

Rav: I remember the first time I DJ’d at a daytimer, with all these older guys who had been doing this for a long time. For them, it was just another gig, but for me, it was figuring out what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. But daytimers kind of stopped by the year 2000, partly because so many venues were closing down. Plus, maybe clubs were realising opening during the day wasn’t necessarily beneficial for them, and with the underage daytimers there was a lot of safeguarding with, say, 1,000 kids, and you’re not making that much money if you’re just serving them Cokes and lemonades. And by then, Asians were being allowed into mainstream nightclubs. And most of the kids who had been going to the daytimers were old enough to go to the nighttime gigs.

Ritu: Mid-90s onwards, I don’t remember there being that many daytime gigs, because it had all moved to the nighttime. After the success of Bombay Jungle, venues opened up to Asian promoters. But also, priorities change. A lot of the DJs and promoters got married, got ‘real’ jobs, they didn’t really have time any more. Most of the bands still exist, though. The Bhangra scene never stopped.

Bobby: For me, daytimers stopped when I went to uni and I stopped having to go during the day. There were people coming to your halls of residence selling coach tickets to Bhangra parties around the country — Leicester, Birmingham, Nottingham. Suddenly the seal really was off: there was no getting dressed in the toilets, and people were getting off with each other. To me, that was so radical! You didn’t see girlfriends and boyfriends kissing each other at daytimers, ’cos you still imagined a cousin’s cousin or someone would see, the paranoia was rife! But the moment I went to the uni gigs in 1990, that was it: there were no cousins of cousins! People were getting off in the dark corners of the clubs. And then Bombay Jungle was starting, the Asian Underground kicked off, I moved on. But those daytimer gigs started off what’s now become my life’s obsession.

Rav: Daytimers didn’t happen in any other music scene: this was our thing, it was so important for Asian culture. I rarely meet people with a bad word to say about them. It was where bands were born, where DJs were born — and in terms of my career, it’s where I was born.

Rani: To this day, I’m still in contact with people that I DJ’d with or went to gigs with 30 years ago. It’s just lovely.

Bobby: What happened with daytimers could only have ever happened in Britain in the 80s. It’s so unique, it needs to be celebrated with as much vigour as we celebrate punk, the New Romantics, the summer of love — and I mean that musically, socially, and artistically as well.

Rani: I didn’t do it for womankind or anything, I did it because I wanted to — it just so happened Ritu and I were the only women, and so we happened to create a platform for women to be able to participate in this stuff now, whereas it wasn’t acceptable before. I can see the parameters have changed and attitudes have shifted with all the women coming through in the scene now. I like to think we helped create an environment for South Asian women in this country to do what they want to do.

Rav: I’m glad that there’s a generation of Asian people that can remember those great times and I’m glad that there’s a new generation of people that are trying to bring that through in a different kind of way, unapologetic about the way that they’re doing it. I love that. That’s exactly what daytimers were there for.