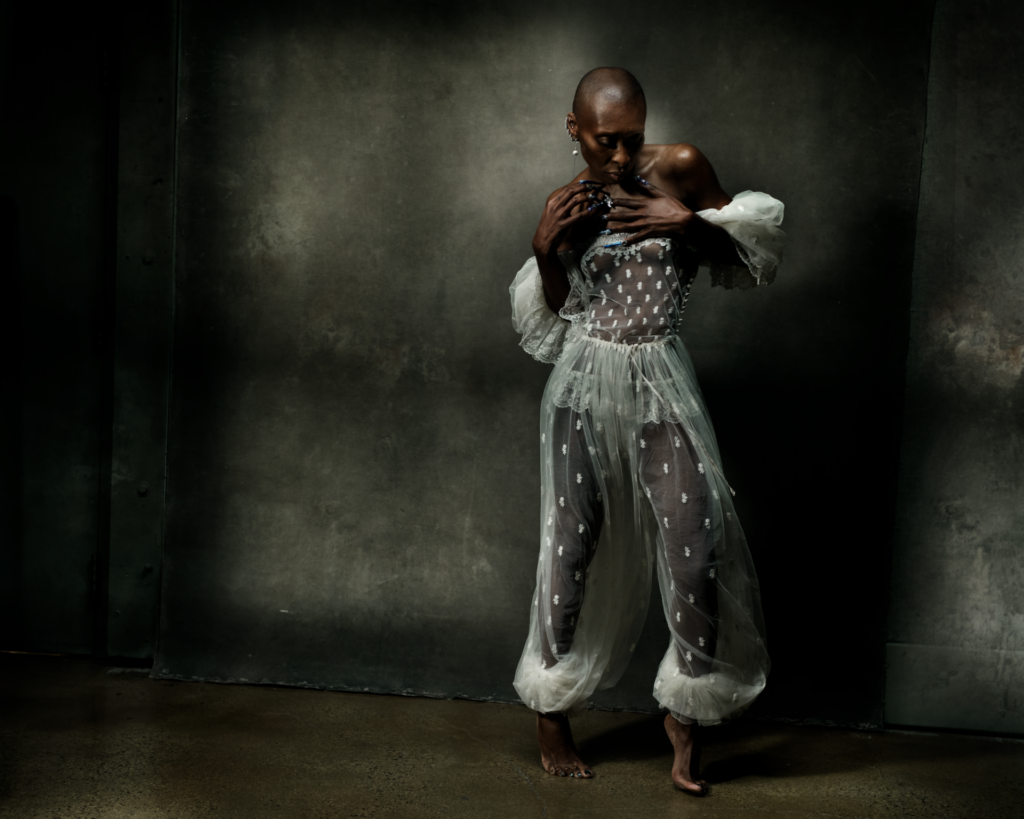

Cynthia Erivo: ’It’s up to every individual to decide who they are – a rule or law doesn’t change that‘

The ‘Wicked’ star discusses new album ‘I Forgive You’, dissecting daddy issues and embracing identity in a time of political pushback

The end of last year and the 2025 awards season was dominated by two distinct colourways: pink and green. As the Wicked train arrived in town, singer, songwriter and actor Cynthia Erivo and co-star Ariana Grande were unavoidable. The film promo cycle that launched a thousand memes, Wicked surely wins gold for sheer relentlessness and cultural pull. Fortunately, the film and its lead performances delivered with both Erivo and Grande receiving adulation for their respective roles as Elphaba and Glinda in the alt take on the Oz classic.

One might expect them to grab any private moment between the maelstrom of press interviews and red carpets to put their feet up and indulge in a back rub in a plush hotel suite. Not Erivo. During the course of filming the hit musical’s screen adaption and its ensuing press circuit, she was using the rare days she had to herself to dig into her psyche and unpick past experiences for second album, I Forgive You.

“It took a little bit of patience, determination and discipline,” Erivo says of the album’s creative process. “Whenever I had the day off, I would be in the studio or at home writing. I’m not one of those people who goes into the studio and sits for seven to eight hours overnight, smoking, drinking. If we’re in the studio, we are going to make music. It was really concentrated. This is a little sacred temple that we’re making music in, and I think it’s probably why we got it done.”

Much of the record was completed during the Wicked press run. “That was insane, because it was like, ‘Okay, so I’ve got this day off, we’re not needing to go anywhere, so I’m going to spend this week in the studio.’ My producer and I were working on text. When a mix comes in, I’d listen to it and he’ll be doing the editing wherever. Sometimes we’d be like ships in the night, I’d be in London, or in Italy, South Africa.”

The result is a deeply personal record that examines past relationships, an estranged father, and her ongoing personal growth. It’s an intimate dissection of all that pain and the eventual joy that comes with acceptance. It’s a mighty showcase of Erivo’s voice in all its rich glory, from the smallest inflections on the softest notes, to those sailing high notes. For somebody with such a small frame, it’s remarkable to hear how much mastery she has over her instrument. I ask, does she ever scare herself with how powerful her voice can be? She smiles at the thought. “No, it doesn’t scare me. It does definitely feel like a release. I always think of it as my balance. I’m small, but I’ve got something else that lives inside me.”

The album is in four parts. Was that intentional or did it materialise that during the recording process?

It all just fell that way. I was supposed to write a lot less, only 10 to 13 songs. And then I kept going.

One of the things that struck me first was that the songs are self-contained – they end, which doesn’t really happen a lot in music, a lot of music just fades out, but all the songs are tidy snapshots of a story. Why was it important for you to do that?

That’s just how my brain works. That’s how I hear the music: a beginning, middle, and end. That’s how they wrote themselves, and that’s how I hear it. Even if it’s an instrumental end, I need the song to end almost like giving the listener the permission to just take a breath before the next thing starts, knowing that is one story and now we’re moving on to the next one. There’s one where the song ends and you hear footsteps, and then the song starts. When the continuation happens, it’s intentional, it’s on purpose, as opposed to, ‘we dunno how to end this, so this just plays out.’ I don’t want to do that.

I guess because that’s such a personal album, it’s important to allow each song to exist in its space.

That’s right.

You don’t hold back in your lyrics.

It came naturally. I don’t really know how else to write. The scary thing is actually just giving it to people because you forget that, ‘Oh, this is going to go somewhere.’ That’s the scariest part, actually sharing it.

You describe yourself as quite a fearless person in terms of putting your emotions out there.

Now I am. I don’t think I always was. When I say younger, I mean 10 years ago, I was still a little bit guarded. It’s taken time for the walls to come down and for me to let people in.

There’s a stark difference between the growth in our twenties and that of our thirties. Your twenties are when you just go out there and have fun. But then your thirties are often when you settle into yourself.

I feel like that’s what my thirties have been, a real sort of coming to myself, settling into myself and figuring out who I am, and who I want to be, and also becoming okay with continuous growing. It never stops.

Why was it important for you to revisit past relationships in the album?

I feel like I was a different person in those relationships. I sing about a couple of different past relationships. Some of those things were terrible to experience, but I also wasn’t perfect in those experiences. And I think it’s okay to sort of look back and go, ‘Oh, actually maybe that wasn’t just the other person. Maybe that was me as well. Maybe I wasn’t so perfect in that.’

If they realize the song is about them, that’s okay. I never thought about whether or not it would hurt anyone’s feelings. There are no names on purpose. I’m not identifying a person, but if a person understands that it’s them, then hopefully they get to have a little bit of retrospective thought. Maybe they can have hindsight and look back and go, ‘Oh, I guess that behavior wasn’t that great. And maybe I won’t do that in my next relationship.’

You experiment a lot with your voice on the album, there’s even yodeling and wailing.

I want to say it’s like East African, that particular sound at the end of More Than Twice, I just wanted to see how much I could use my voice. I wanted to see how open I could be, and I wanted to use my voice in ways that I hadn’t necessarily experienced before.

But I’d never recorded it, used it on a song, or sung like that in front of anyone. I really wanted to pour as much of myself into this as I possibly could. For me meant how much of your voice have you been holding back? And if there’s anything that you haven’t used yet, maybe it might be time to use it. There are the sounds in the background where it’s me using a classically soprano voice for the harmony, or it’s me breathing.

You’ve got me using my nails at one point. It’s percussion. I think you have the sun be crying at some point. The breath I use as percussion at some point, I use a lot of my falsetto. I pitch things a lot higher in some places, and I’ve used the base area of my voice, which I never get to use. I just wanted to see how expansive I could be with my voice.

How would you describe that time for you, your childhood and growing up?

I think there was a simplicity, but there was also complexity. I was going to school, trying to figure out what I wanted to do. It’s that weird time where you are like a kid who thinks they’re older and then you are growing into a young adult. That time is so strange because you are just trying to figure it out. And it’s also for me, the time I was trying to figure out what I was, and that’s when I started realising, ‘Oh, I like boys and I like girls. Do I have a crush on this person? I dunno what’s going on.’ And you don’t have the language for it. So, I’m sort of keeping it to myself at the same time and not saying anything.

When did you first realise you were different?

About 15, I think I always knew I was odd. I never felt like I fit in, but if we’re talking about sexuality and not necessarily seeing it the way as everybody else, about 15. I felt a little bit separate. I didn’t have anyone to talk to. Even if I did have someone to talk to, I’m not sure I would even know what to say or what to ask or how to talk about it. I had plenty of boyfriends, some of who I just absolutely didn’t need to be with.

Do you remember a day or a moment where you looked in the mirror, or walked out the house, and you felt for the first time comfortable in your body?

The day that comes to mind, is when I had an audition, age 24. I’d seen a few people go to auditions that I was in and seeing them dressed in character and I just thought, no. I went in a short sleeve, thin knit, I think it was grey, and some jeans and flat shoes, and I’d cut my hair. It was like a low cut, but it was still short, and I felt so myself. I remember I walking into the audition and I felt so myself that it actually didn’t matter if I got the job or not. From that moment, I have been progressively becoming more and more like myself as time has gone on.

Sometimes it’s those little moments that matter most, and it’s not even the most groundbreaking event or the biggest revelation.

Yeah, I felt really clear about it. I just felt so comfortable. I remember the day was kind of warm, the sun was out. I just remember feeling really steady. I sang something from Dreamgirls and I felt really comfortable and in my head I was like, I don’t think I’m getting this role. Also, I don’t really mind, but go in anyway.

Did you get the role?

No. I don’t think I was meant to.

Well, the universe gave you that something else.

Yeah, yeah, yeah!

On the single ‘Replay’, you sing about “daddy trauma”. How did you deal with the trauma of that separation when it happened to you aged 16?

I think I used the anger and the feeling of abandonment and betrayal to dig out a path in front of me using it as the fuel to keep going and keep doing things. Almost like a way to prove to someone that ‘you’re going to miss out, and I’m going to make sure that I do really well, so that when you look and you miss me, you’ll feel sorry about the fact that you did this.’ That’s what it was for a really long time. But I think that’s what I did with it. I funneled that energy into trying to do well.

And then from music to acting, this idea of embracing authentic identity has really been quite central to a lot of your work in many different ways. In Wicked, you’re playing a fictional green witch, to your role in Harriet.

The more I had to play these roles, the more you have to put a bit of yourself into them, and they inevitably leave a little bit of themselves with you, and so I think the more I’ve done these roles, the clearer I’ve become about myself.

After years of progressive thinking and conversations just recently in the UK and US, it feels like the language around trans and gender nonconforming people has taken a step back. Would your message be to people who gender nonconforming?

I would say don’t allow other people who have a lack of understanding, or a wilful lack of understanding, define who you are or want to be or have been since you were born. It’s not for anyone to decide who or what you are. It’s up to you. It’s up to every single individual to decide what and who they are, and a rule or law does not change that. It is what it is. Don’t seek out the acceptance of people who don’t want to accept you. Just seek out the acceptance for yourself.