How Bicep created one of 2022’s must-see live shows

The Northern Irish duo’s dynamic stage show was one of the summer’s most impressive festival sets. Ahead of two headline shows at London’s Alexandra Palace this weekend, the band and show designer Zak Norman explain how it came together

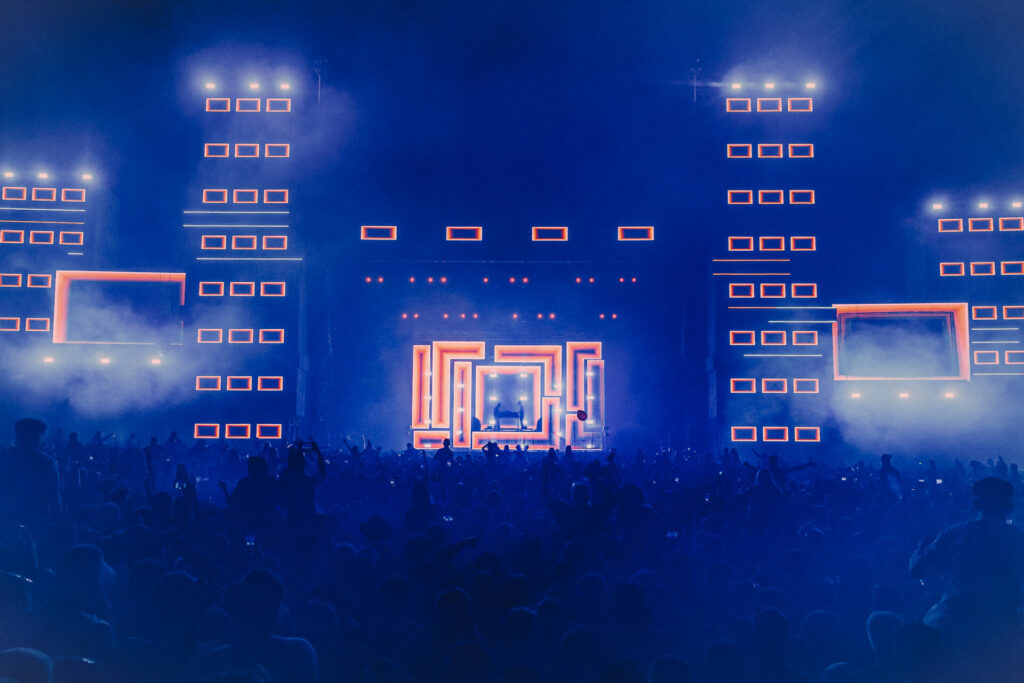

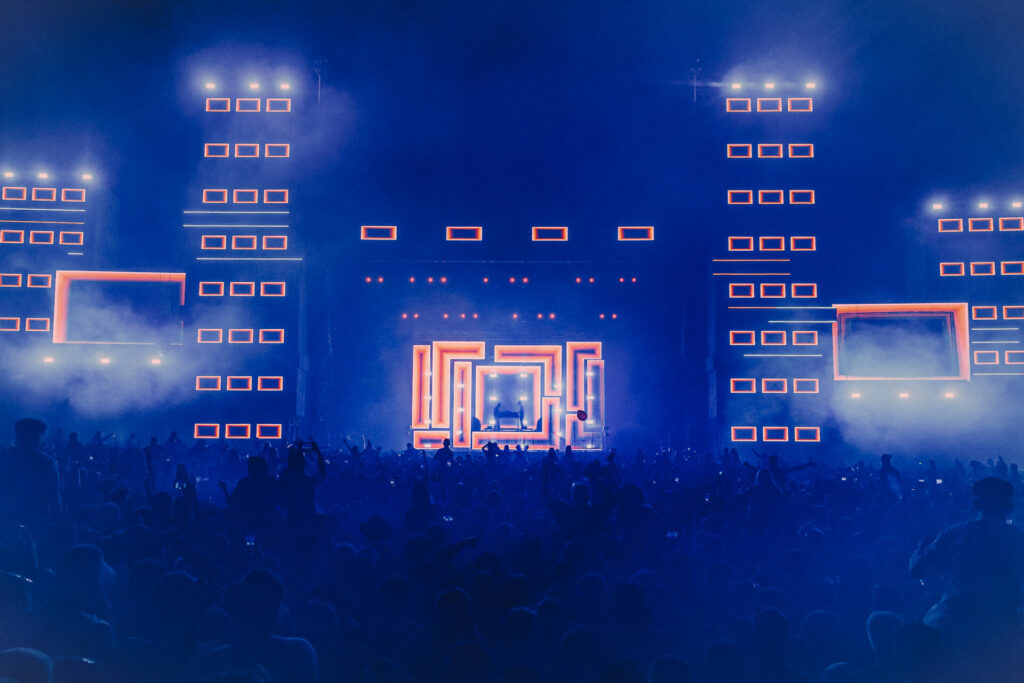

Every Monday morning from May through to September this year, Instagram was flooded with photos and videos of Bicep’s live show. From Glastonbury to Creamfields, Primavera to Parklife, the Northern Irish duo’s live set was one of the festival season’s must-see sets, its rainbow lasers and dynamic visuals splattered all over social media after each and every weekend. Off the back of their second album, 2021’s Isles, the pair and their team have created an audio-visual masterpiece of a live show, fluid and evolving but unmistakable in its identity. If you didn’t see it in 2022 — well, you missed out.

Over the past decade, newer electronic acts have found it increasingly hard to break into the top-tier of live acts in the genre, with legacy acts like the Chemical Brothers and Kraftwerk still occupying headline slots the world over thanks to their mind-bending audio-visual spectacles. While certain newer acts — like Fred again.. or Overmono — saw success across 2022’s festival circuit, it was Bicep who truly ascended to the top of the table.

Elevated on a platform and facing inward towards each other, Bicep play entirely live, mangling their recorded music into new shapes that can be calmed down or amped up depending on a show’s atmosphere, setting, the response of the crowd and more. A certain amount of their visuals — warped images and bright lights presented by banks of screens flanking the pair — can also be triggered by the band on stage, allowing them to break free of the kind of rigid structures that often hamstring live electronic acts. With their iconic flexed bicep logo still the show’s focal point, Bicep and their team have added striking colours, stadium-filling lasers and more to create a stunning spectacle that’s never quite the same each time you see it.

The journey to this all-conquering audio-visual spectacle began in 2016, when the duo — Matthew McBriar and Andy Ferguson — put together their first live show after years of DJing and making a name for themselves through their influential Feel My Bicep blog and label. During an opening weekend of live sets, the duo played the Resident Advisor tent at London’s Field Day, where the visuals for the day were handled by Zak Norman, who operates under the Black Box Echo pseudonym. “We’d been working on the stage all day, and I wanted to make something look different,” he remembers of the day, which closed with the debut Bicep live set. “I didn’t know Bicep at that time, but I was very bored of being in that tent.”

To mix things up, Norman piped in “apocalyptic levels” of smoke into the room, adding tense layers of atmosphere to the show, backed by the rudimentary visuals the band had brought with them. “I remember leaving and thinking that I shouldn’t have done it, and maybe that I ruined this band’s set,” Norman laughs, and, upon receiving a call from Bicep’s manager the next morning, expected a dressing down. Instead, he was invited to work closely with them on progressing and evolving the live show, a job he has had ever since.

“He had a really natural knack of understanding how the room worked,” McBriar remembers of Norman. We had never even spoken to him or briefed him on that day, and didn’t know what he was doing with the visuals until after the show when we saw videos of it. We knew we needed to get in contact with him.”

Coming from graphic design backgrounds themselves, Bicep knew from the start that a quality visual element was paramount to any success their blossoming live show would have, and the first iteration of their live show was based on the artwork for their self-titled debut album from 2018. “The brief for the artwork was about bringing order to chaos,” McBriar says, and while the chaotic element of the live show came from broken apart elements of the artwork flashing their way across the screen, solid panels and boxes of light surrounding the duo brought a sense of structure. “We’ve been so fortunate to work with so many creative people that have taken the simplest ideas and concepts and pushed them as far as they can. But at their core, they are very simple in their purest form.”

Norman adds of Bicep: “They’re really visual people, and they’re very good at talking about the feeling that they want to produce. I don’t know how much we went into specifics in the early days; it was more about the energy that they wanted to be in the space. There’s a lot of tension and release in their music, so it was about having those epic moments of euphoria, but then not being scared of darkness. We didn’t want it to be something that was watched — you didn’t need to pay attention all the time, it was more of an energy.”

After tweaking and evolving the live show across its first four years, the pandemic offered Bicep and their team the vital time and space to reconsider and re-mould their show for the festival main stages and cavernous venues that it seemed obvious were awaiting them. With the band set to enter rehearsals for a 2020 tour on the day lockdown was announced, they instead spent those months dissecting and breaking apart the musical and visual elements of their show, hoping to piece it back together in a way that worked more seamlessly for themselves on stage and those in the crowd.

“One thing I find with other people’s live shows is that you can’t really rag it — our live show is raw and rough”

— Andy Ferguson, Bicep

“As amazing as the show was in tour one, and as happy as we were, it was quite sloppy,” McBriar remembers. “Lots of cues were missed. There were moments when we dropped big crescendos and all the visuals or lighting was totally lost — it was almost too live.”

To rebalance this issue, Norman developed a program on a computer that allowed the band to control elements of their visuals through their own laptops on stage and condense or stretch particular segments of their songs on a whim. With the use of timecodes, the band could experiment and improvise more, but within a more structured framework that stopped the whole show going off the rails. At a recent Los Angeles show, Ferguson explains, the band stretched the set to seven minutes longer than normal (usual live shows using timecode have to keep to within a single second in order to work), while they sometimes fall a minute or two short of the expected length for any number of reasons.

Both for the musicians’ enjoyment and the reward for fans who come back time and time again, playing as live as possible is central to the experience of Bicep’s show. “One of the main things I find with other people’s live shows is that you can’t really rag it,” Ferguson says. “Our live show is raw and rough. Our goal isn’t to keep stuff on a grid like a band would. It’s to deconstruct it off that grid.

“I can distort my synths to make it slightly out of tune and sound almost like techno,” he adds, “or at other shows I’ll keep it quite soft and pure. It just depends on the location you’re in and how you’re feeling as well. I don’t have that thing in my head where it’s like I’m playing the same songs over and over again. It’s saying, ‘How can I change this to suit my mood?’”

Take the band’s biggest hit, ‘Glue’, for instance. On some evenings, the live version that closes their set is warped beyond recognition before bending itself back into shape. In renditions that frequently pass the 10-minute mark, little sprinkles of the song are dropped into an extended intro before its iconic topline finally emerges alongside hugely Instagrammable rainbow lasers, which somehow look great on the grid even when captured on a phone after a handful of drinks. “It feels like it’s true to ‘Glue’, but doesn’t feel boring to us,” Ferguson says of the track’s evolution, which serves as the apex of the band’s show. “We understand that people come to see that song, so don’t want to deviate to an entire weird remix that doesn’t feel the same,” McBriar adds.

For Norman, the melting together of seamless visuals and a fluid, experimental live show is the ultimate paradox for modern electronic artists: “It’s a really interesting quirk of how dance music works,” he says. “You either want the perfect show, or the freedom to play live.” With Bicep, he’s managed to create the rare opportunity for both.

During their sets, the band face each other on a platform in front of bright screens. Considered by the band as a vital development of their live show, the band wanted to “differentiate the idea of DJing, which is associated with facing forward, and performing a show.”

“As exciting as it is, two guys hunched over a bunch of synths has been done a lot before — it wasn’t that interesting then, and it’s not that interesting now,” McBriar jokes, adding that there are “no big guitar solos” in the show, or much time for the pair to walk around the stage. “There’s not much of the show where we aren’t bent over and concentrating.

“We need to be able to communicate a lot during the show,” McBriar adds, and “this is the most logical way to do that.” Norman describes this development as “the most important thing we’ve ever done on that show, because it creates this intimacy between them that I don’t think you’d get if they were facing out.”

The idea for the band becoming silhouetted then arrived after Norman and the band took inspiration from Vince Staples’ striking visual show for the tour behind 2017’s Big Fish Theory album, where he performed silhouetted in front of an orange background. “We watched it at a festival in Ireland and had a real moment,” Norman remembers. “It just looked so epic, and it was amazing how something with so much simplicity could be so powerful.”

The band describe the recorded versions of their songs as designed for “home listening”, and it’s playing to thousands of people in venues and festival fields that has necessitated the songs undergoing evolutions that take them closer to becoming pounding house anthems. This summer, the live show continued to become a living organism of its own, so much so that the band have spent the time in between tours and festivals writing new music specifically to fit into gaps in their set where they felt they needed a new type of energy.

New single ‘Water’, released at the start of October, was developed over summer to fill a part of the live set that needed a magnetic vocal part and some four-on-the-floor punch. “It was made specifically to service this particular gap in the set,” McBriar explains, with Ferguson adding: “We had about six songs in a row in the set without a prominent vocal, so needed something with a bit of energy.” As a result, Bicep worked backwards for the first time, filling in a gap with new material rather than bending their existing material into holes that needed to be filled for the intended rise and fall of their live show.

In early December, the duo will play their biggest shows to date — two sold out nights at London’s Alexandra Palace — and as they call Rolling Stone UK from their cosy Shoreditch basement studio, they’re currently working on more new pieces of music to slot into the show. To do this, they wrote out a rough setlist for the shows and the corresponding BPM of each track, before setting about writing music to fit the required tempo and carry them from one song into the next. “It’s so different from aimlessly just sitting in the studio and thinking, ‘I’m gonna write an EP today’,” McBriar says. “With this, we actually write for a feeling and a specific time. We know what goes before and after.

“You either want the perfect show, or the freedom to play live”

— Zak Norman, show designer

“The live show has been an amazing thing to be able to write music for,” he adds. “It’s allowed us to see holes in the show and think, ‘How do we fill that? What emotion can we put into that hole that lifts you up and drops you somewhere else?’” Through the musical and visual evolution of their live show, Bicep have become a radically different band, and one of the best live acts in the country.

“We come from a design background where precision is such a good thing, and obviously parts of dance music are quite precise,” McBriar says. “But we’re increasingly finding that through a lack of precision, and feeling through mistakes, you hit on and learn the little glitches, and then they become part of the song.” Fizzing and alive, advanced by technology but not robotic, Bicep’s show is — both musically and visually — live electronic music at its dazzling best.

Bicep perform two headline shows at London’s Alexandra Palace on 2 and 3 December 2022.