Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett on 25 years of Gorillaz: ‘If you have the ideas, then keep moving forward’

The brains behind the revolutionary, industry-shaping animated band discuss always staying one step ahead, and why their quarter-century celebrations are “retrospective, not nostalgic”

It’s a daunting job approaching a 25-year milestone with two creatives who prefer not to “get into that world of nostalgia for too long,” as Gorillaz co-founder and visual artist Jamie Hewlett puts it. But seemingly even those most resistant to the past can’t help but get a little misty-eyed.

“Not to quote myself, but Modern Life is Rubbish,” says Damon Albarn, discussing the lay of the land for new artists today and the challenges which perhaps didn’t exist 40 years ago, from lack of small venues and demands to produce content, to the big industry behemoths who suck up resource without giving back. “I’m getting nostalgic now,” he admits. “It was truly a wonderful time, the 80s, to be a young musician. So many places you could play, and you could still go to art school. Has better music ever been made than the music made by slight outsiders from art schools?” The future is just the composition of everything that’s been before, “slightly decomposing,” he surmises.

The future is something Albarn and his bandmate Hewlett have always been striving for since the turn of the millennium when they launched Gorillaz. To celebrate 25 years of the band, they have opened a new exhibition called House of Kong in London and announced a special run of one-off gigs, where they will perform their first three albums front-to-back, before a final ‘surprise’ show.

The retrospective nature of the celebrations sits right on the line of how backward-glancing the pair are comfortable with being, given the relentless pursuit of the new that Gorillaz has always represented. Albarn appears on Zoom, knackered from rehearsals for the upcoming gigs, admitting that he always seems to have three projects on the go; Hewlett, an hour ahead in France, squeezes in a quick chat and a cigarette, already in the midst of his next body of work.

Born out of those magnificent 80s, the duo would each go on to have successful careers throughout the following decade, Albarn with Blur and Hewlett with Tank Girl. The pair arrived at the end of the decade somewhat jaded by the shifting pop landscape. Lad culture and Britpop had become tiring, with little room for experimentation, and MTV was full of manufactured acts at the peak of the boy band boom of the new millennium.

From their shared first-floor flat in Notting Hill, west London, the pair cooked up a plan to employ the same principle behind these MTV regulars, with their ghost writers, but to do something transgressive and meaningful with it. They would create a band with no physical presence and an entire colourful world for them to inhabit. It would exist almost exclusively within their website, with even their interviews being entirely manufactured. “It was our way of satirising the pop movement, or the way pop was going, in a way of making it feel authentic” Albarn remembers.

“Within the DNA of Gorillaz, there’s a lot of what popular culture is these days.”

Damon Albarn

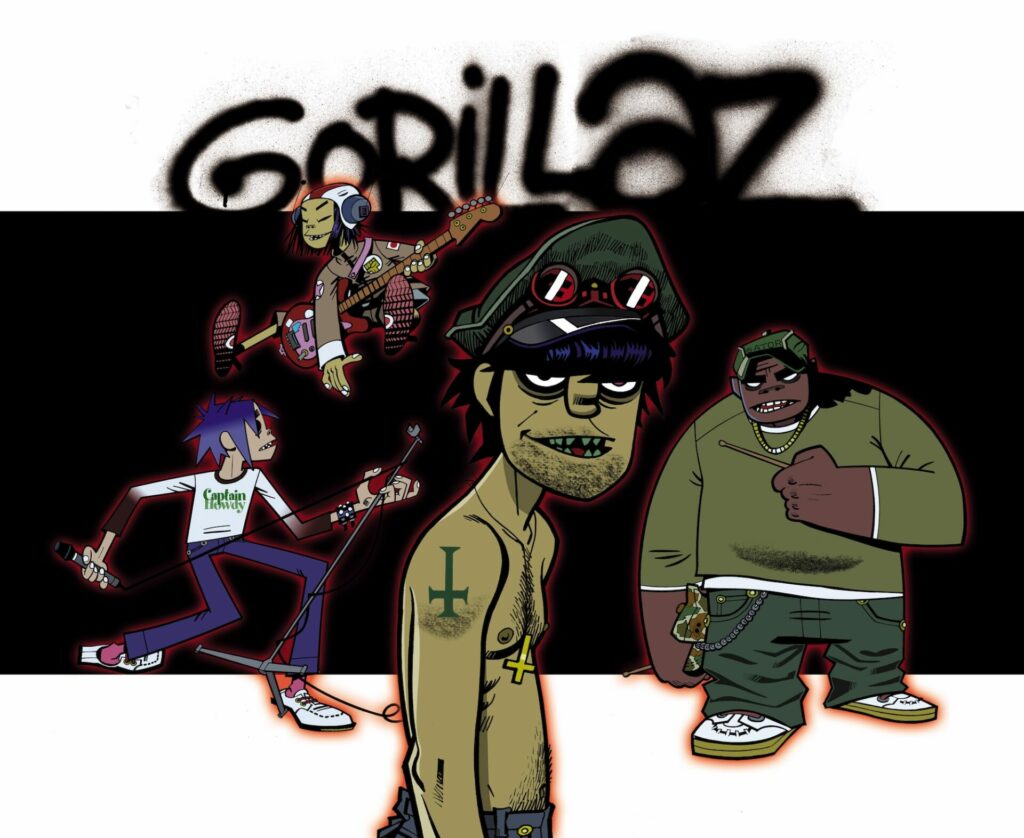

To do this, they drew together four animated outsiders and introduced the world to a ground-breaking new prospect in the early-internet world of music: Gorillaz. Comprised of Murdoc Niccals, the “snaggle-toothed” bassist and band leader, 2-D, the softly spoken frontman and keyboardist, Noodle, a 10-year old Japanese guitar prodigy, and Russel Hobbs, the hulking drummer with “the ability to summon up the ghost of dead rappers”, the quartet would release their eponymous debut studio album on March 26, 2001. The record brought acclaimed single ‘Clint Eastwood’, featuring Del the Funky Homosapien, to the masses.

“When we made the first album, there was this feeling that it was kind of a joke, or it was for kids, or no one was really taking it seriously,” reflects Hewlett. “The music industry liked the music but weren’t really buying the cartoons, whereas young kids were really enjoying the cartoons, and through the cartoons getting into the music, and then through the music, discovering artists that they would never have discovered otherwise, like your Bobby Womacks, or your Ibrahim Ferrers, or your Becks.” Collaboration has, from the off, been the beating heart of Gorillaz. “It’s what we are,” Albarn concurs.

By the time they came to release their second album, Demon Days, in 2005, they had created a format which has since become dominant in pop music – that every song should have a guest, for good or bad. “Probably for bad,” Albarn chuckles. Whilst not a completely unique prospect, with him citing Massive Attack and the likes of Aerosmith crossing over with Run DMC as light-touch examples of collaboration, Demon Days explored the concept in a more “chest out, weird pop way.”

With the success of the record, it became an appealing format for the music business to co-opt, yet where mainstream pop collaboration now seems reserved primarily for social media and newsworthy moments, festival headline sets, and to double listening figures, Gorillaz continue to work empathetically, in a way which promotes cultural exchange, with a “real story behind it”. Through Gorillaz, the world of hip-hop was opened up to Albarn, something he previously knew little about. He’s since worked with a host of high-profile rappers including the late, great MF Doom, De La Soul and Snoop Dogg.

“It’s amazing, really,” he reflects. “I’ve learned so much. You’re delving into everyone’s personal histories when you make music together, because it should be a very intimate experience. You’re being quite vulnerable with each other. To make proper music properly, you have to be very open with each other.”

It’s something they addressed early on in the original manifesto they wrote upon launching the band, a single side of paper which has since sadly been lost to the ether. In it, Russel’s special power was a very loose idea that you could work with anyone. It’s “kind of forward-looking, in a sense, because it predates the whole idea of holograms and all of that,” says Albarn. “I suppose within the DNA of Gorillaz, there’s a lot of what popular culture is these days. I don’t really want to blow my own trumpet,” he adds, typically unselfishly. “It’s obviously better if other people do it.” And we’re more than happy to oblige…

Despite being written off as a gimmick by the industry, the animated band would go on to release eight studio albums, two documentaries, host their own music festival, collect numerous awards and accolades, publish two books and even obtain a Guinness World Record for the Biggest-Selling Virtual Band. On top of that, they pioneered a progressive use of digital media, animation and the internet to build out their virtual world, gaining an enduring, committed fanbase. Then there’s the matter of the mind-boggling number of cross-generational collaborators from the worlds of animation, film, and TV, as well as music. They’ve employed a cast of established voice actors, including a cameo from late acting great Dennis Hopper, who narrates ‘Fire Coming Out of the Monkey’s Head.’ For their sixth studio album The Now Now (2018) the band also welcomed a crossover with The Powerpuff Girls when Murdoc was temporarily replaced, due to imprisonment, by Ace, the leader of the Gangreen Gang.

It’s a community expanded even further sonically with musical legends and future stars, from Grace Jones, Elton John, Mavis Staples, The Clash and Terry Hall, to Little Simz, Kano, JPEGMAFIA and more (a lot of people “I’ve at some point hugged,” Albarn laughs in wonderment). Hewlett’s ability to adapt his artwork to the digital and virtual zeitgeist of the time has allowed him to continually build out an engaging, expansive narrative with his illustrations. And Albarn, with his near-pathological pursuit of creating, learning and collaborating in music, generates unlimited sonic possibilities. Gorillaz, as such, still feel just as relevant and necessary today as they did at the start of the millennium.

“Politicians are liars. We don’t believe them anymore, so we find strength and inspiration through other things.”

Jamie Hewlett

25 years on though, at 57 years old, Albarn admits that he had a hard time getting his head around the fact that he’s “not so much of a pop proposition” anymore. Yet animated characters, with their agelessness and consistency, generally speaking, have long allowed us to navigate the trickery of the world independent from the high standards we hold real life, complex human beings to. It’s a point which Hewlett has long been trying to prove with these characters.

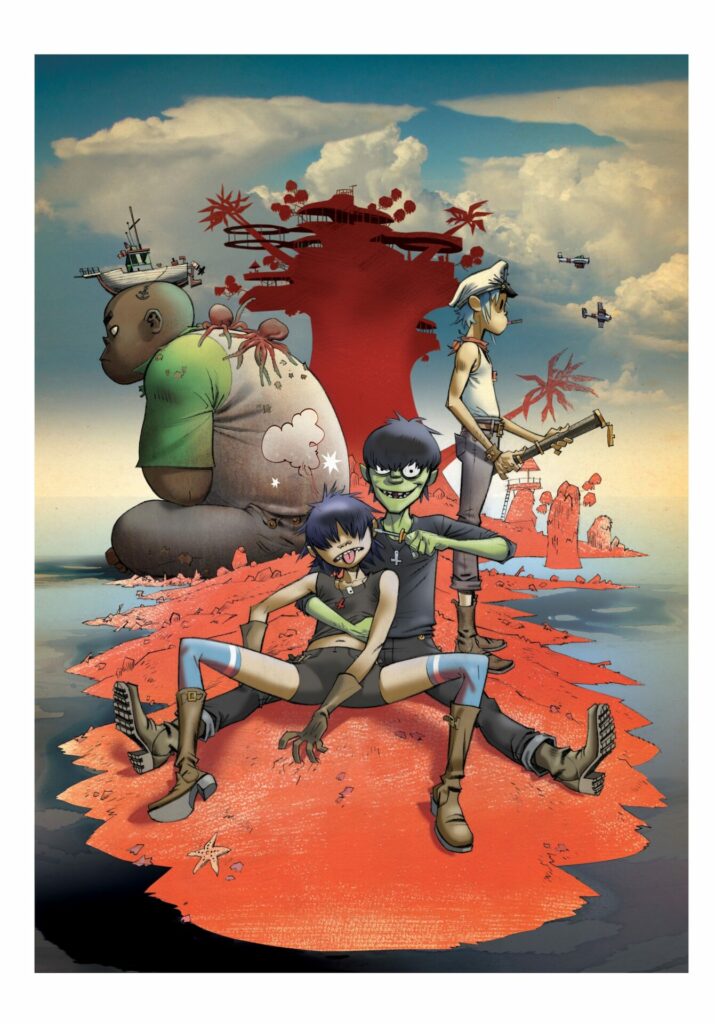

“I felt they were important, and I’d grown up on that stuff, and I understood that they were for adults as well,” reflects Hewlett of his love of animation. He cites the works of Miyazaki and movies like Akira, with their adult themes and powerful storylines despite the childlike connotations of animated work. It’s something Gorillaz have long adopted, subtly approaching socio-political themes through their music, with Demon Days drawing on the anxiety of a post-9/11 era, followed by the environmentally conscious Plastic Beach (2010). 2017 record Humanz also does well to capture the uncertainty of an unstable political climate around the time of Trump’s first inauguration.

“25 years later, we’re at a point where animated characters and avatars are such a huge part of our lives, especially for the younger generation who live through computer games and wear skins and go to cosplay,” the illustrator muses. The draw of these virtual worlds is appealing to young people for whom real life has become so unpleasant that they don’t want to engage and so feel more comfortable in these spaces. “Whether or not that’s a good or healthy thing,” he jokes, “it’s better than taking drugs.” But, through characters, “if you’re engaging young minds, then there’s great things you can teach them through music and animation, and the storylines, and the political statements that we want to make.” Yet, whilst Hewlett has reservations about the impact of social media (and with Albarn not even in possession of a phone), it’s a lens through which he notices a great quality in their younger audience.

“When they get into something, they really invest in it, and they research everything. I see conversations on social media when I post something, and they know more than me about what I’ve done. I’m like, ‘Shit, they know everything.’ They’re really invested deeply into it, and I think that’s really great,” he explains. “I think kids would rather listen to what Cartman from South Park has to say than what fucking Keir Starmer has to say, you know what I mean? So that’s where we are in the world. Politicians are liars. We don’t believe them anymore, so we find strength through other things, and inspiration through other things.”

On August 8, the Copper Box Arena in Stratford, London opened its doors to House of Kong, “an exhibition like no other” (as Murdoc Niccals gives testimony). The arena, originally built as a multi-sport venue for the 2012 Summer Olympics, had been partly transformed into an immersive, walk-through Gorillaz experience, celebrating the band’s quarter-century. As I headed down to delve headfirst into the band’s chaotic world, I met a father and son duo who embodied this idea of the enduring appeal of animated characters.

Where 44-year-old Bartek Szwejkowsky came to the band whilst working in a club in the 00s, his son, 13-year-old Oliver, came to them through his dad. “The great thing about Gorillaz,” Bartek says, is “all the graphics. It’s not about music only. It’s about the whole experience of the music that they are delivering.” To still capture the minds of a younger generation, 25 years on, is “amazing,” Bartek concludes. When I recall this interaction separately to both Hewlett and Albarn, they’re visibly touched and (briefly) allow themselves the satisfaction. “That makes it all worth it when you hear stuff like that. I love that,” Hewlett says. At the time of forming the band, the friends both had very young children and wanted to do something their kids would be into. “I think that’s the greatest thing about Gorillaz, that it appeals to children and their parents. That’s something I’m very proud of,” the singer adds.

The exhibition was created by Swear (the minds behind Banksy’s Dismaland and Glastonbury’s Block9), and runs for four weeks at the east London venue. To mark its closing, the band will then play four unique live shows where they will perform their first three albums complete with the original stage shows from the era. To end the residency and the anniversary celebrations, they will play one final ‘mystery’ show, details of which are yet to be released, though fans reckon a new album could be unveiled.

For Hewlett and Albarn, the above marks the limit of what they are comfortable with as a celebration of the band’s quarter-century milestone without “milking it,” as Hewlett puts it. True to form, even as we discuss the forthcoming celebrations, they make it more about the future than the past.

“Doing these four records exclusively in their own era, and almost verbatim in the track listing of the albums, doesn’t feel like it’s nostalgic,” Albarn offers. “It feels retrospective, which is different. It’s a different thing because you’re not so much using it as a vehicle for entertainment – you’re presenting it as a piece of work.” It’s how Albarn convinced himself that indulging in this way was ok. He admits that he doesn’t listen to his music once it’s done, in part because having to listen so obsessively to something until the day it’s mastered shatters the illusion. “It’s impossible, because you know every single piece of the mechanics that went into it,” he says. Yet in listening to these three albums ahead of the one-off shows, he notes how his present self informs the way they’re playing the first album.

“I think that’s the greatest thing about Gorillaz – that it appeals to children and their parents.”

Damon Albarn

Gorillaz was made before starting his travels around the world, where he would spend a significant amount of time playing music in Africa. His encounters with so many “amazing, incredible” musicians would transform him. “I was trying things on that first record which I now can do unaided. I can play those rhythms – I don’t have to manufacture them through the trickery of recording or sampling,” he explains. “It’s interesting. I mean, it’s not dramatically different, but I think it’s… I don’t know. It was good, whatever it is. Whatever’s happened is not bad!”

Some things haven’t changed so much, though, even to his own surprise. “I can’t quite believe I can still hit the falsetto,” he jokes of the debut album. “That first record has a crazy amount of falsetto.” It was, he says, “definitely … related to the drugs I was taking. I was a much more irresponsible human being. I was hitting some notes I really didn’t think coming back I’d be able to hit again.” With age comes responsibility though, and giving up smoking a year-and-a-half ago has given him a “little more of a chance” with his voice this time around.

As for Hewlett, he similarly justifies the exhibition and the live shows as being more of a reminder of everything that has happened over the last 25 years than anything else. “I’m not into nostalgia, even though it’s a very powerful drug for some people. I don’t care what you did 25 years ago,” he says. He cites David Hockney as his “guru,” an artist who, at 85, is still changing his style and ideas, and is “ahead of the game every time he releases”. Despite this, when walking around his exhibition, the artist couldn’t help but feel a prang of pride, before duly pulling himself back in. “When I start working on something, I have the image in my head of what I’m going to draw, and then what I end up putting on paper isn’t quite as good,” he says.

The artist is forever chasing the brilliant image in his head, something he describes as never being quite achievable, but each time he gets a little closer. “I think that’s why I like going forward,” he says, “because I’m still not content. I’m not satisfied. It must be better, without torturing myself.” He and Albarn are almost symbiotic in their joint pursuit of perfection and the new. “There’s always so much more to do,” Albarn says on the subject of completing an album, “so I have to finish [it]. I don’t really have a choice. I have to go on to the next thing at some point.”

“If you can make it, you’re welcome – after that, it’s back to the new stuff,” concludes Hewlett of the 25th anniversary celebrations for fans. As for the new stuff? “For me and Damon, it’s just… it’s fun. We get to do whatever we want to do. Damon gets to make whatever music he wants to make. He’s not in a band anymore, he’s free to experiment,” Hewlett says, before summing up the revolutionary manifesto of Gorillaz in one line: “If you have the ideas, then keep moving forward.”