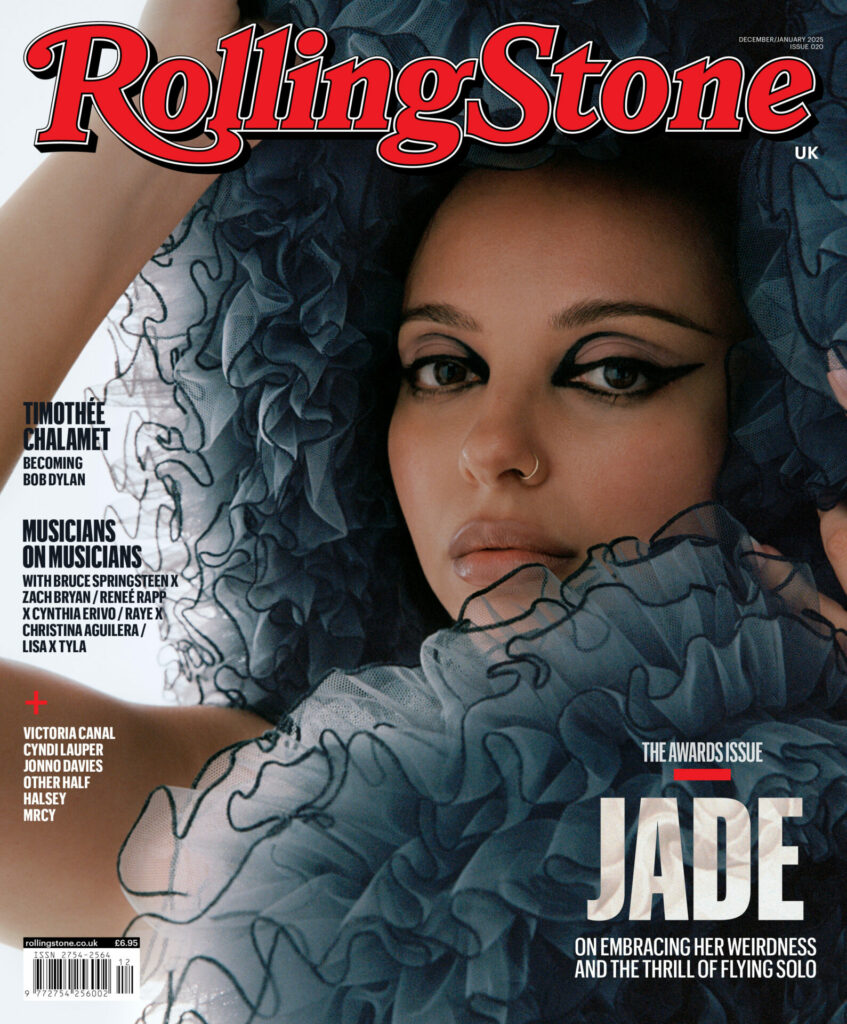

JADE: pop star of her dreams

From the safe confines of the second biggest-selling UK girl group of all time with Little Mix to stepping boldly into the spotlight on her own terms with a jagged, leftfield take on pop, Jade Thirlwall — aka JADE — is ready to embrace the thrill of flying solo

By Hannah Ewens

Jade Thirlwall was only 14 when she first presented herself for judgement. She put on her best leopard-print headband and bravely sang some of Whitney Houston’s ‘Where Do Broken Hearts Go’ in front of the X Factor panel. “You’re a funny little thing, aren’t you,” remarked an amused Simon Cowell, like a cat playing with its food. Louis Walsh then jumped in with: “Unusual!” In response, Thirlwall thanked them with an unwieldy grin.

For this tiny singer, it would be a case of third time lucky. After being put through to boot camp twice, she auditioned again at the age of 18, now wearing leopard-print trousers. Judge Kelly Rowland told the naturally shy teenager she’d be good in a girl group, an idea that Thirlwall was completely unimpressed with. She was resolute about being a solo artist and an unusual one at that.

Rowland, of Destiny’s Child fame, had correctly identified herself in Thirlwall. That season of the show, Thirlwall was placed in what would become the second biggest-selling UK girl group of all time, Little Mix. Their accolades could fill an infinite scrolling Wiki page. They were a well-oiled commercial pop machine amassing billions of streams with hits like ‘Black Magic’ and ‘Shout Out to My Ex’ while touring stadiums until they went on hiatus in 2022. “I didn’t see myself as a conventional girl’s girl. I was nerdy and quiet. When they told me I was gonna be put in a girl group, I automatically thought of Pussycat Dolls,” she laughs. “I thought, ‘Oh no, I’m not sexy — and if they’re bitchy, I’ll struggle because I’m not confrontational at all. I shrink at any drama.’ But it turned out to be the best thing to ever happen to me for my confidence and understanding of sisterhood.”

Tonight, I’m sharing wine with her at a table in Shoreditch House to discuss the fact that Thirlwall finally has what she wanted: she is the solo pop star she always dreamed of being. “I’m a bit of a dark horse,” the Rolling Stone UK Trailblazer Award winner tells me. “I’ll try anything once. I don’t see myself as a safe person creatively and I am a bit strange. All my life I’ve been told I’m weird.” Her bandmates and friends saw it, her boyfriend, Rizzle Kicks singer Jordan Stephens, saw it, Cowell clocked it after only minutes in her company, and now the rest of the world gets to see it.

Outwardly, she didn’t seem like the biggest personality in the band, but behind the scenes, Thirlwall had been the creative driving force and business mind. For her solo project, that incisive playfulness is fully on display. From the horror-influenced visuals to the Drag Race inspiration, Thirlwall — whose solo artist name is JADE — is more aligned with Charli XCX than Little Mix. On the addictive lead single, ‘Angel of My Dreams’, she switches between a Y2K sound, hyperpop and a nostalgic girl band chorus gone wonky to tell a story about the dark side of the music industry, a theme that is repeated across her presently untitled debut album. It’s smart and entirely unexpected.

In person, Thirlwall has the same excitable offbeat energy she had as a 14-year-old in her first audition. She’s like a conspiratorial friend primed for gossip exchange: she directs me to a clip that circulated from a Little Mix interview where fans thought she was on cocaine because she was pulling odd faces. “People don’t believe me even now,” she laughs, pausing to sip on her rosé. There were bad moments and dramas when she was in the group, of course, but she’s prepared for the same to happen in her solo career. “I’m never going to discredit what we achieved. I don’t have anything bad to say about it, so I wouldn’t stir anything up, just to look cool,” she laughs again.

The group’s young fanbase has matured with its members. Thirlwall doesn’t see it as her responsibility to appease them or tell them what they should and shouldn’t do. “I’m 31 years old, I’m gonna write about stuff I experience, my merchandise will reflect that, you know what I mean?” One such recent merchandise bundle includes sex aids. The other day, while recording with Sugababes, she told them what’s included in the package and had to explain to Keisha Buchanan what a butt plug is, much to her amusement. This is an older and wiser Jade Thirlwall having even more fun.

“I spent my whole adult life with the girls. When we first stopped, I was lost. I was like, ‘Every decision I’ve made over the past decade hasn’t been my own.”

Thirlwall grew up in a household of eclectic tastes in South Shields, a seaside town near Newcastle. Her mother was a Motown fan who looked like Diana Ross, while her dad listened to 80s power ballads and VH1 classics. Her big brother — who she aspired to be like as every younger sibling does — was deeply into the happy hardcore-clubland classics era of the 90s and 00s. It was a happy childhood, in part due to the fact that there’s a strong Yemeni community in South Shields (Thirlwall is half Arab: one-quarter Yemeni, one-quarter Egyptian). “I have a lot of memories of my grandad cooking curries or waiting for him outside the mosque,” she remembers. “I listened to his prayer and Arabic music, too.” It wasn’t until she went to a Catholic secondary school, where she felt alienated, that she began to struggle with racist remarks and her feelings of anxiety. She was bullied by other girls, hence her initial reservations about being in a girl band.

While she was in Little Mix, she didn’t understand that she could have spoken out more about her race. “I’d only ever seen negative stereotypes of Arab people in the press, so I was scared to promote my heritage,” she says. “I feel sad for my younger self that I could’ve been the representation I needed back then. I try to make up for that now.” Thirlwall has been outspoken about issues close to her heart. Whether it was attending Black Lives Matter protests and pro-Palestine rallies or becoming an LGBTQ+ rights ambassador for the UK charity Stonewall, she stands out among many of her peers for her political verve.

Each of the girls knew a year ahead that Little Mix were disbanding, so they individually spent that period preparing in the studio. “It took me a long time to figure out how to not write a Little Mix song because that’s all I’d done for a decade,” admits Thirlwall. Panicked about the idea of having so much stillness after the group, she made an abundance of music in a bid to find her sound as soon as possible. This became an advantage: so sure of what she wanted to do, Thirlwall was able to approach potential labels with a fully formed vision. After signing with RCA of Sony, they assured her she could take her time to release her solo music, which came as a surprise: in the pop world, two and a half years is a long time to disappear. “In hindsight, I was freaking out about existing without the group and thought I had to jump on the hype of us just disbanding. If I’d released then, I would’ve been anxious and have put so much pressure on myself to be as big as [Little Mix] was.”

“When they told me I was gonna be in a girl group, I thought, ‘Oh no, I’m not sexy – and if they’re bitchy, I’ll struggle because I’m not confrontational.”

Nerves were amplified because it was her first time striking out alone. “I always associated Little Mix with my womanhood as I spent my whole adult life with the girls,” she says. “I didn’t know how to be a woman in my own right. When we first stopped, I was lost because I was like, ‘Fuck, every decision I’ve made over the past decade hasn’t been my own.’ It took me a minute to get my independence back.”

Does that feel codependent now looking back? “100 per cent, we were codependent,” she says resolutely. “Any relationship can become a bit toxic, or the boundaries aren’t necessarily there, but we were family and joined at the hip. After the group, I was terrified to even go to an event on my own because I had to talk to people. We’d go to an event and just talk to each other in the corner. You feel safe when you’re in a group because if something doesn’t go well, you can say, ‘Oh, it wasn’t all me.’”

While each member was planning their solo material, they were supportive of each other but kept their future careers highly confidential. This wasn’t a collective decision but an unspoken rule to not talk about music or ideas. “We knew we needed the space to figure out who we were without feeling influenced by one another. I didn’t want to compare or hear their music and think ‘God, am I doing the right thing?’ I just didn’t want to know. Fans and critics will compare our work, so I don’t think we should be doing it, too.” While that is true, it’s impossible not to make comparisons when the other members of Little Mix have pursued a more straight-forward pop route.

If Thirlwall was in charge of the music industry, it’d look different. Sure, it’s improving for artists because social media means “you can’t get away with as much bad shit”, but there’s some way to go. When I ask her how she’d change it, she sits up in a businesslike manner and adopts an Elle Woods from Legally Blonde tone. Before she’ll answer that, she’ll take me back to the nagging feeling she had that something wasn’t right with Little Mix. The four girls were presented with different contracts and told who their team was, and she didn’t feel she had a choice.

To all intents and purposes, Thirlwall and her fellow Little Mix band members were child stars. She agrees with this assessment. “I almost think you shouldn’t be allowed to be a star until you’re 18. I’m so glad I was turned away and didn’t get put in Little Mix until I was 18 — and even then, I feel like that was too young,” she says.

Previous X Factor winner and South Shields born-and-bred Joe McElderry had warned Thirlwall of his negative experiences in the industry. “I remember him saying make sure your mum’s there when you’re doing all these important signings. But I was too young to understand what he meant, and I made the same mistakes as him.”

It wasn’t until halfway into their career that the young women looked around and wondered who that person in the room being paid to be there was or why their peers and friends were making more money than them. Thirlwall and bandmate Leigh-Anne Pinnock helped to write the Little Mix music but weren’t signed into a publishing deal until 2019. Unfortunately, it was a “really shit deal” that they were stuck in but at least she was finally recognised as a songwriter, financially speaking. (For her solo career, she has not signed a publishing deal because she now finds it hard to trust the entire framework.)

If she were queen of the industry, her first decree would be to introduce a comprehensive course that artists take as soon as they’re signed by a label (if not sooner), that teaches them what a label deal is, how royalties work and how they make their money. That would prevent the type of situation that Little Mix got into when they were first signed. “When you come from a working-class background, you get your advance and think you’ve made it, but you have to recoup everything back. You’re getting all these lavish cars and making them wait for ages, but you’re footing that bill eventually,” she laughs drily. She would also introduce the sort of mental health care she’s managed to negotiate as a solo artist with her new label: a substantial pot of money that she can use if she needs therapy.

The topic of mental health brings the conversation round to Liam Payne, the One Direction member who tragically died in an accident while under the influence of drugs in October. He was Thirlwall’s peer — the only X Factor pop group to outperform Little Mix by any metric was One Direction, with the two groups frequently spoken about in the same breath — and was once her friend. They both had their first auditions during the same series, aged 14. The pair returned a second time: Liam went through to the finals and was placed into One Direction while Thirlwall was sent home. Payne was encouraging of Thirlwall and told her she had to keep trying X Factor. She was then put in a group on a later series. They fell out of touch over the years, but she was naturally upset to hear of the news for both him and for his family — their mothers are still friends.

“When the news broke out, it did shake me up because we’d started the same, but we’d ended up on very different paths. We both wanted to make it so much and sometimes that is a blessing and a curse to get what you’ve dreamed of. It’s unbelievably tragic,” she says of Payne’s death.

Just hours after it was reported that Payne had died, Thirlwall was due to start a heavy day of promo for her single ‘Fantasy’. She cancelled it as she didn’t feel like she was the right person to be fielding questions about his passing so soon after it happened. After all, she hadn’t been close to Payne over the past several years. “All I can speak of is who I knew he was when we were kids, and he was someone that wanted to make his family proud,” she reflects. “He wanted to be a singer more than anyone I knew.”

“It did shake me up because we’d started the same, but ended up on very different paths. We both wanted to make it and sometimes that is a blessing and a curse.”

When Thirlwall wants to achieve a special goal in her life, she writes it down or puts it on a mood board. Yes, it’s a manifestation technique, she says, but psychologically it feels good to do it for yourself. Recently, two items were written down: working with photographer and music video director David LaChapelle and having a critically acclaimed debut album. She’s not religious but believes that “everyone needs something to believe in, even if you don’t follow a certain faith.”

LaChapelle reached out to her via her DMs. She thought it was a fan account but soon found herself walking through the doors of his LA studio to the sound of her track, ‘Angel of My Dreams’. He had pictures of her on his own mood board and an array of baked goodies for Thirlwall to try since he heard she loves biscuits. They bonded over a mutual love for divas like Diana Ross and Bette Midler and created the disco-dancing Carrie-inspired music video for the single ‘Fantasy’.

Now it’s time for that critically acclaimed album. “I know, right, one thing at a time,” she says with a grin. While the rest of the record is strictly prohibited, I’m allowed to hear a preview of electro-pop track, ‘That’s Showbiz, Baby’ at her photoshoot earlier in the day. “I’ve been describing it as the cunty little sister to ‘Angel [of My Dreams]’ because it’s a similar concept but more aggressive,” she says. It’s queer club night ready and cements a future for her as a major-label budget, underground-feeling pop girl. Just like ‘Angel of My Dreams’, it’s deliciously chaotic.

Sonically, she wanted the album to feel like she was experimenting with who she is as an artist — because that is exactly what is happening. “I’ve come off coffee because I was craving feeling frantic all the time. I’m obsessed with that feeling,” she says. “My brain is chaotic, and I’ve been in writing sessions telling producers to change the tempo or genre part-way through the song. I like never feeling safe with a song.” The roll-out has been designed to have the same feeling: random, daring. This album is the “throw the kitchen sink at it” record. Sophistication and sonic cohesion might happen in a few albums’ time. “On this one, I wanted the feeling of being slapped around the face by a pop star,” she smiles.

Some songs are about her partner Stephens because she fell in love at the beginning of the writing process. One track, called ‘Unconditional’, is about her mother, who suffers from lupus and various illnesses (“All my life I’ve had the frustration of not being the one who can help her or save her,” she shares). Another track is directed at her father, describing how she knows he did his best in their relationship. The writing process has been healing for her. “There’s an overarching theme of owning my own decisions, whether that’s through love or the music industry,” she says.

Thirlwall’s dream has never wavered: to be respected as a solo artist. She knows that when she presents herself for judgement this time, many commercial pop fans will not like it. I think they’ll appreciate that JADE is ambitious — that what she’s done is unusual.

“This is about doing everything I’ve always wanted to do,” she says proudly. “I’m pleasing my inner child, as cheesy as that sounds. She’s so happy that I get to do this.” When she performed as grown-up, solo JADE recently on Later… with Jools Holland, she pictured her younger self there in the audience: “She was absolutely beaming because I’ve made it.”

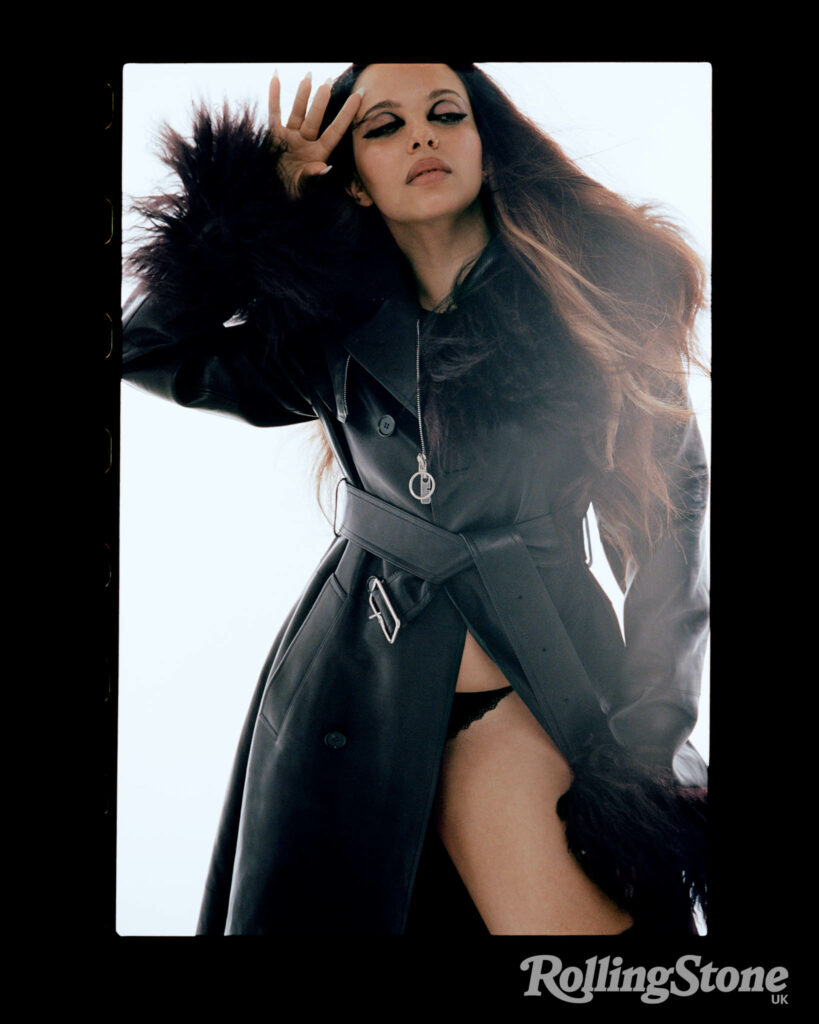

Photography by Harry Carr

Styling by Zack Tate and Jamie McFarland

Makeup by Grace Ellington

Hair by Aaron Carlo

Lighting techs: Luke Stulinski and Frederico Covarelli

Fashion Assistant: Aaron Pandher