Linder Sterling: ‘Super women are coming into their own’

Linder Sterling tells Rolling Stone UK about the genesis of her latest exhibition, Women in Revolt!, and the place of punk in 2023.

“Women in Revolt! is an exhibition of women’s ingenuity, joy, rage, daring and triumph,” says artist and musician Linder Sterling.

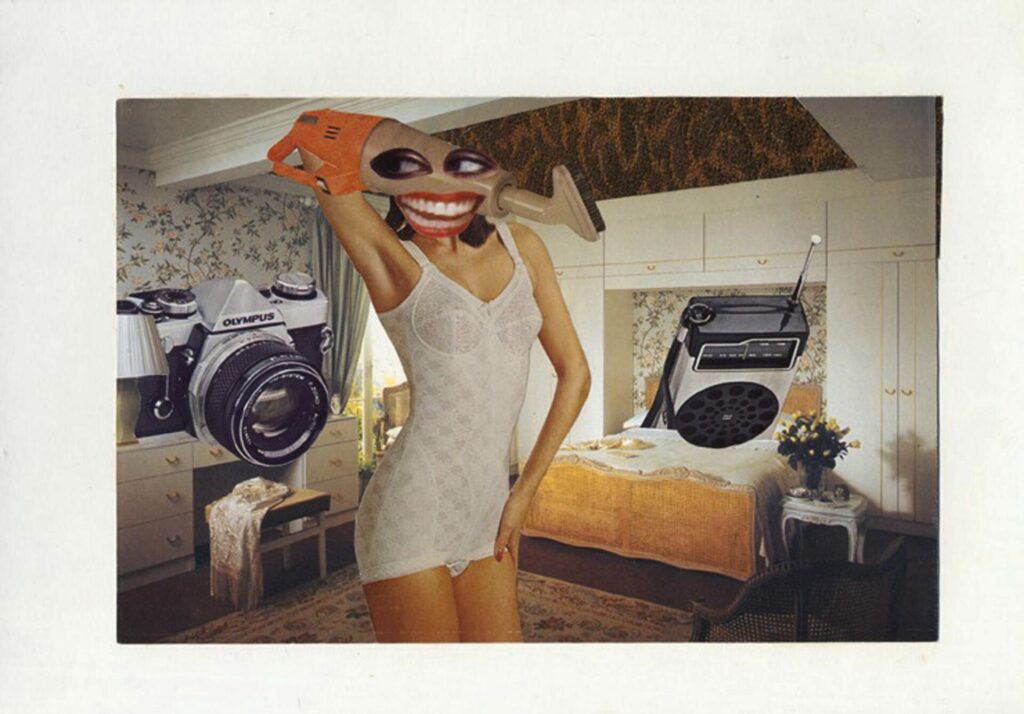

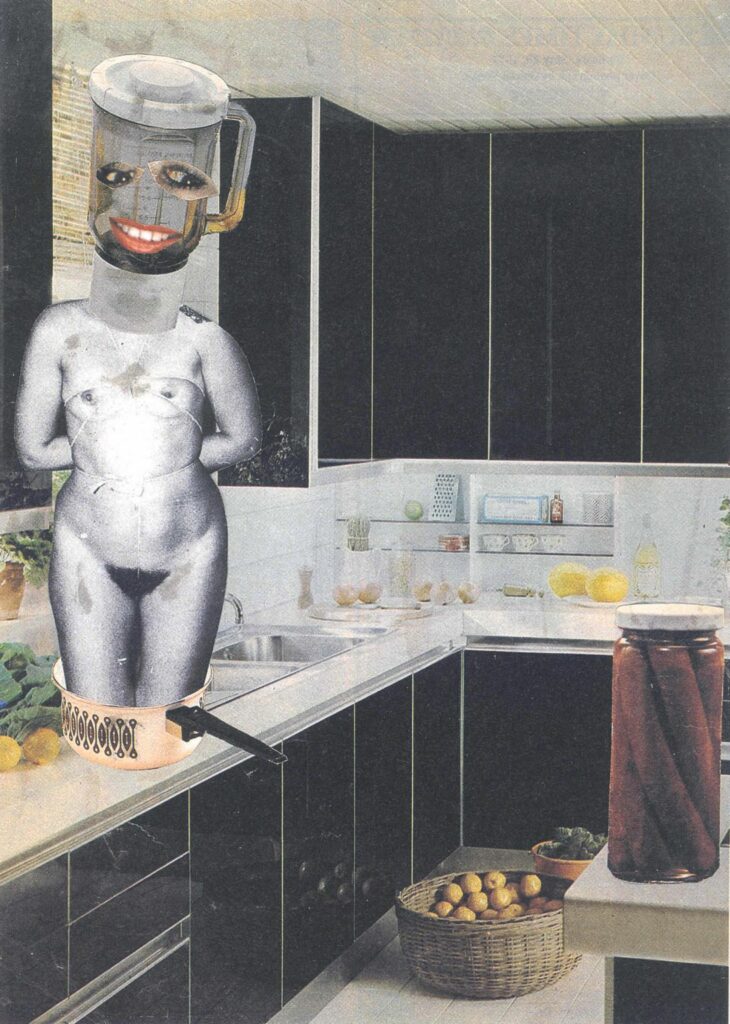

Known for her subversive photomontages which splice images from consumer culture and glossy glamour magazines, the likes of which grace the sleeves of Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict, as well as for founding the Manchester-based post-punk outfit Ludus, it’s no surprise that Linder’s work sits amongst the abundance of women artists included in Tate Britain’s latest show.

Presenting two decades of radical feminist ideas set against a backdrop of social, economic and political change, Women in Revolt! features more than 100 female artists working in the UK. Spanning everything from punk and protest, and ending with the collapse of the Thatcher regime, this celebration of women’s enduring struggle to be heard and their invaluable contribution to British culture is explored through painting, photography, collage and much more. “Each time I visit I learn something new and this newness spurs me on beyond the doors of the museum,” Linder tells Rolling Stone UK.

With a career that has spanned over five decades, Linder’s work has been informed by and played witness to an ever-shifting cultural landscape and attitudes towards women and their places in and contributions to society. In this interview with Rolling Stone UK, Linder gives her thoughts on the impact of such a curation of work in the context of now, the notion of ‘punk’ in 2023, and the intersection of art and music.

You’ve made artwork for Buzzcocks and Magazine, performed in a meat dress long before Lady Gaga and incorporated choreography and music into the Diagrams of Love installation. I wondered if you could explain a little about the intersection of music and art for you? When you founded Ludus alongside your art practice, how did one influence the other and, maybe, did it ever feel like there were limits to one that the other allowed for in what you were trying to say?

Linder Sterling: As a child growing up in Liverpool in the 1960s, I was karmically privileged to experience the birth of pop music on a very visceral level. The sound of the Merseybeat permeated every home that I knew of. Earlier in the 1950s, Liverpool had birthed Lita Rosa, the first woman to ever have a number 1 hit in the UK charts. I grew up then with the sense that rock and pop were always just around the corner, and that glamour could be home grown and in abundant supply.

Those formative years created a template of sorts so that when I was ready to explore the world of music as a young woman, it was out of great curiosity, like Alice in a sonic Wonderland. Music and performance generate movement whereas the act of creating photomontage demands a very steady hand engaged to a very steady body. I thrive on the two extremes. Photomontage demands absolute solitude whereas performance demands company, it’s not all about me, I leave my ego outside the door as I welcome others into the creative process. On a good day we all surprise ourselves and each other.

The Women in Revolt! vinyl launching alongside the exhibition celebrates women working in underground music in an eight-year period, featuring Ludus amongst the likes of Slits, Cosey Fanni Tutti and The Raincoats, to name a few. Could you tell us a little about what it was like being a woman in music at this time and why the music that was being made between 1977 – 1985 was so vital?

LS: Reading Ludus reviews written by men from those times can be very interesting, the writers really struggled to find a shared language! One journalist asked me if I ever sang when I was menstruating and I replied that I was menstruating there and then. His eyes opened wide so I reassured him that my larynx wasn’t in any way impaired by my menstrual cycle.

Another journalist wrote that the sounds that I made during I can’t swim I have nightmares were the closest that he’d ever heard to the sound of a female orgasm. Readers of Rolling Stone UK may be very interested to listen to that track one day and to question the validity of the claim!

The music made by myself and other women in those times has an inbuilt vitality, we were all making it up as we went along, often with a very slender means. Ludus recorded the six track cassette Pick Pocket in one day because that was all that was affordable. Economy, innocence and determination can make great bedfellows though, we kept going until the engineer switched off the mics.

Most, if not all, of these bands and artists also had their ties to art school scenes. What was the appeal of music and art specifically at this time as a means of communicating and voicing feminist ideas and how do you think that has shifted?

LS: When I decided to study art and design in Manchester, I was the first member of my family to have stayed at school beyond the age of fourteen. There wasn’t any precedent for me to follow, I had to carve out my own path without a familial map to guide me.

I found art school to be an incredibly liberating sphere, even though I never met anyone there who had read the same books as I. From age sixteen onwards I’d voraciously read every book on feminism that I could get my hands on. I first encountered Germaine Greer on Nice Time, a half hour satirical sketch show on Granada TV, Kenny Everett was the arch anarchic host. First impressions are always lasting so that when The Female Eunuch was published two years later, I was very alert to the wit stitched into the seams of Greer’s paragraphs.

When I decided to step onto a stage over a decade later, I wanted to be heard as well as seen. I felt that I’d temporarily exhausted image making, so exchanging my scissors and glue for a microphone felt like quite a moment. Ideas were made flesh.

You’ve previously said that collage was a way of bursting that idealism you see in magazines but where magazines don’t seem to hold the same power that they once did – mainly because of the constant exchange of imagery, information and opinions on social media and the internet – where does that leave the practice of photomontage and collage for you? And in what way has it maybe evolved?

LS: From the early Dada photomontages of Hannah Hoch et al, there was always a stance of heroism and opposition embodied in the glue. Dawn Ades published ‘Photomontage’ in 1976 and for me her book became a road map of the path that I’d elected to follow as well as a compass to keep me on track for the decades to come.

For the first time in its history though, photomontage has been flipped and suddenly slipped under the fence to the dark side. Deep fakes threaten to ruin the lives of girls and women daily. AI accelerates the loss of sovereignty over one’s own image.

My works in Women in Revolt! could be seen as deep fakes of sorts, I cut up photographs from pornography, fashion and interior design magazines to create fake scenarios that in turn revealed the current state of oppression of women. Pornography is always all about profit so there are very few magazines in print now. I used to ponder whether Vogue or Playboy would be the first to collapse first. It turns out that Playboy exists now as purely pixels.

On that as well, how important is the physical act of using a scalpel and cutting out imagery? Does it possess its own statement, separate to the final composition? Is there something in that process that has a lasting concern?

LS: As we find ourselves adrift in a sea of pixelated imagery online, the kinesthetic sense becomes all the more important. We talk about “consuming” images now and “binge watching” the latest drama series as if all appetites can somehow be satiated if you stay online long enough. In the early photomontages seen at Tate, food and the utensils that we consume it with broods metaphorically. I return to scissors and scalpels over and over again, they’re my balm. As a little girl I cut up my one and only best dress and I’ve still no idea why.

My surgeon’s tools, plus endless stacks of books and magazines are my balm. Unlike using Photoshop, there isn’t a sheet of glass between myself and an image. Photomontage can be very visceral, very poised, one slip of the scalpel and I can lose an image forever. A lot of the books and magazines in my collection are irreplaceable. I love the challenge of working with fragile pages, I’d probably make a great surgeon as a side hustle!

When you exhibited at Kettle’s Yard for a retrospective of your work a few years back, how did it feel to see 5 decades worth of ideas, action and context coexist in one physical space?

LS: Intriguing! I felt as if I could retrospectively sleuth my own path back through time in order to make sense of the present moment. So many new meanings ricocheted off.

I’m now in the midst of a repeat process as I prepare for a retrospective at the Hayward in 2025. There we’ll see another chapter in which the DNA of the works presently displayed at Tate Britain begin to play out within AI cultures of deep fakes and endless filters.

The early photomontages showing women with overblown mouths prophesied today’s fashion for lip fillers. It’s interesting to think of photomonteur being a prophet, isn’t it? When I’m long gone, will the photomontage that featured on the sleeve of Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict [which features in Tate’s Women in Revolt!] have a completely different meaning to that of the present moment? I hope that like the Mona Lisa, she will continue to fascinate.

Leading on from that, Women in Revolt! spans a 30 year period of feminist art in the UK, spanning multiple topics against shifting landscapes. With it being the first exhibition of its kind, what do you think its impact is, perhaps for those only just discovering some of those voices on display, for yourself, and for others who are being recognised in the spaces they were, for so long, historically excluded from the narrative of? Is it a celebration, an archive, a call to action, or all three?

LS: Women in Revolt! acts very much as a cultural colour contrast dye. At Tate Britain, we now look at each image retrospectively and each speaks volumes about what was absent in the mainstream media of those times. I think that each generation will make its own unique comparisons to life in the present moment, measuring how far we’ve come and how much further there’s still to go. The show works as celebration, archive, a call to action and more.

Women in Revolt! is an exhibition of women’s ingenuity, joy, rage, daring and triumph. [Curator] Linsey Young and her team have worked tirelessly to create a survey show that in itself becomes a world of its own, a sanctuary of sorts. Each time I visit I learn something new and this newness spurs me on beyond the doors of the museum – the etymology of the latter being “the seat of the muse”. We hopefully all take our seat at the table of the rebellious muses and then take their fruits out into the world.

I read in an interview from a few years back where you’d said about thinking of “punk now as a verb and not a noun?” What does punk in action look like in 2023?

LS: These days, the word punk can be applied to anything that advertisers want to be seen as being edgy in some way, a new mascara or a hue of a new nail varnish. Looking at the photos of punks in 1976, you have to look at the ground that they stand upon, as well as the figures themselves, to really get a sense of just how shocking those days were.

I remember walking through Manchester in 1976 wearing a t-shirt and bondage trousers from Sex. Everyone as one stopped and silently stared, I was suddenly the woman who’d fallen to earth. It was very eerie to walk through such a muted commotion. I and others that I knew were often violently attacked because of the way that we looked and the music that we listened to, the police in turn were unsympathetic. It could all get very nightmarish at times.

In the present moment, I don’t know how we reintroduce a sense of the eerie and of the unsettling, nor do I know if anyone particularly wants to engage with those modes right now. Life is perhaps far more complicated in the present moment than in the 1970s, maybe fashion can’t shock us anymore, we leave that role to incompetent politicians now.

Thinking of etymology again, with “punk”, down at the tap root are notions of worthlessness and acts of prostitution. In a culture obsessed with wanting to be seen to be of worth and to be seen to have the moral high ground, it feels radical to consider one’s worthlessness, fragility and fallibility. I would argue that that’s the space where treasures and solutions may hide. It’s no time for Superman now, he’s been made redundant. Super women though are coming into their own, let’s take heed of all that they say.

Women in Revolt! is on at Tate Britain until 7 April 2024. Purchase tickets here.