2022: the year that the Queen died

Following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the UK entered an official 10-day period of mourning. One journalist — a staunch republican — recounts what he saw

The Queen is dead, and you are crying. Your misty-eyed reaction may have been one you long anticipated, or it may have taken you quite by surprise, but whoever you are, and whatever your reasons, you know some aspect of the Queen’s death moved you far enough beyond mere sadness that you shed actual tears. And you were, according to a YouGov poll, just one person among 44 per cent of Britons (which, in theory, encompasses 29.6 million people) who cried.

You are not like me. I was among the 54 per cent whose eyes were left dry and heart intact after the Queen’s passing (the remaining 2 per cent were apparently so head-spun by proceedings that their minds stopped recording their emotional reaction altogether and left them only able to respond to YouGov’s grief audit with “don’t know”). That isn’t to say the majority of the country harbours anything resembling the kind of republican sentiments that I do. In fact, in the 11 days between her dying and her funeral, further polling found that Queen Elizabeth II’s death has resulted in a tremendous boon for the net popularity of the royals. If these trends continue, by my calculations, we are approximately four more monarch deaths away from statements like “the UK should continue to have a monarchy”, “the royal family is good value for money” and “I’m proud of the monarchy” becoming unanimously agreed upon, incontrovertible truths on these fair shores.

I’d always known that Queen Elizabeth II was personally popular, particularly among those of a certain vintage. But I’d considered the wider royal family to be possessed of a soft and waning popularity, and that any fondness directed their way arose out of a sort of Stockholm Syndrome collective coping mechanism at having to learn to live with them as a background facet of our lives for so long, the way you might with a birthmark or a cracked phone screen. Even if they liked Lizzie herself, didn’t most people agree with me on the basic premise that the divine right of kings and queens is an absurd and antiquated thing that should be abandoned to history?

Turns out: no. There is a disorientating gap between the way I experience life in Britain compared with so many of my apparent compatriots.

The Queen is dead and I am in the pub. It’s been 30 minutes since the news was announced. It is fresh, emotions should be raw, and yet there are no overt displays of monarchism to be found here. The mood among my fellow patrons is one of shared revelry to be living through one of the most inarguable “Where were you when…?” moments in history. Nobody has slammed a petulant fist into the bar, thrown a pint glass across the room, or upbraided us all for failing to put on our proper suits, do up our ties, and sing the national anthem. In truth, I’m slightly disappointed. I’d thought there’d be a palpable tension between ardent monarchists and exuberant republicans. Without that frisson, this occasion feels robbed of a certain anecdotal potential.

The Queen is dead and you are outside Buckingham Palace. You got there early. A few hours ago, Huw Edwards changed into his mourning attire, and it became clear that Her Maj was being ushered into the shadow realm. The moment her death was announced, you and the congregation of Britain’s most efficient mourners burst into a rendition of‘God Save the King’. The drab, droning nature of the song robs the moment of any poignancy, rendering it comic and vaguely embarrassing. Over the years, there have been many half-hearted attempts to change the national anthem to something more emotive, rousing, tear-jerking, something that isn’t in a bizarrely difficult-to-sing 3/4 time signature and which maybe even contains the faintest whiff of a melody. ‘Jerusalem’, perhaps, or ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. But inevitably all of the mooted alternatives will fail, for none can rival the lyrical content of‘God Save the King’ for its obsequious belief that anything beyond the crown is irrelevant.

“Even if they liked Queen Elizabeth herself, didn’t most people agree with me on the basic premise that the divine right of kings and queens is an absurd and antiquated thing that should be abandoned to history? Turns out: no”

The Queen is dead and I’m outside Buckingham Palace with hundreds of others. It’s been a few days since she died now. I’d wanted to witness the mass hysteria that had long been predicted when this moment came to pass, the kind that supposedly gripped the nation after the death of Princess Diana. There’s none of that here: no one breaking out into inconsolable sobbing, no one holding a lighter aloft and belting out ‘Candle in the Wind’ 1997, no one violently shaking the gates, throwing their head back and bellowing “WHY???” at the heavens. It was all quite restrained; pleasant, even. Strangers milling about convivially, families laughing between themselves, mourners throwing thumbs-ups and beaming for selfies. It certainly wasn’t a solemn or funereal atmosphere.

The general cheer and hubbub makes the whole affair feel more like something you might clock in the What’s On? pages. Something to pop along to so you could say you’d been, like a Secret Cinema event. I try to pause in front of the whole scene, to drink in some feeling of historicity at being here in the aftermath of this, but am quickly hectored by a steward to “keep it moving along, folks,” until I end up in the adjacent Green Park, home to the official public shrine.

I’d hoped to see at least a few bizarre and eerie tokens left by grief-addled strangers, but either the stewards were methodical about removing them, or people simply hadn’t taken leave of their senses enough to have laid down a selection of their favourite ElfBars or a full casserole dish of lasagne for Queenie. Instead, it was a sea of flower bouquets and cards, occasionally interspersed with Paddington Bears and marmalade sandwiches in zip-locked bags (in defiance of signage specifically asking people not to leave anything other than flowers and cards there). Some of these offerings had been neatly arranged into makeshift mazes or giant letters spelling out ‘Elizabeth’, but a lot of it had been left to pile up in great big mounds, bursting at the seams.

“Even if they liked Queen Elizabeth herself, didn’t most people agree with me on the basic premise that the divine right of kings and queens is an absurd and antiquated thing that should be abandoned to history? Turns out: no”

I ask one of the stewards what will happen to everything once the mourning period is over. He tells me that the majority of it will be composted. And the Paddingtons? He shrugs. “Probably chuck ’em, to be honest.” This is the closest the occasion has come to moving me. It’s fairly apparent that a lot of the tributes have been left by very young children, or at the very least, took time and care to source and compose. A lot of it has already been completely buried among the other detritus, where it will remain until discarded. I imagine a five-year-old being told that the card they spent hours lovingly crafting has been hoofed into a landfill along with their favourite Paddington toy they attached it to.

I’m snapped out of this as my thoughts return to the death of Diana, the earliest news event I have any memory of. This recollection isn’t vivid, and almost all of the key scenes and details are missing, including how I myself reacted to them. I can only recall a dim awareness of it all happening. I was five and it seems entirely probable that my primary school had us compose cards in her honour, too. I can’t imagine I was particularly cut up or even sad about the whole thing, and if I was, it would’ve been because I’d been told to be. If I did make that card, nobody saved it.

The Queen is dead and battle stations have been called. You are an account manager at a PR agency representing a number of Big Brands, and this is your industry’s Chernobyl. Your clients’ futures are in your hands and one wrong move could spell devastation, yet the situation demands an immediate response, for some reason. What is the appropriate thing for Dr Oetker to say at a time like this? Should Compare the Meerkat’s Aleksandr Orlov break character, or deliver his condolences in the client’s approved tone of voice? How can Oddbins tap into the conversation around the Queen’s death and connect with key demographics? Get someone to monochrome all the logos, ASAP — the Dolmio man is currently offering up a bowl of distastefully vibrant ragu, and Lloyd Grossman has already lowered his glasses to half-mast. Stop all the scheduled tweets. Cut off the E.ON customer helplines. Prevent the George Foreman social team from going live with their ‘Grilling Machines for Flame Loving Queens’ campaign.

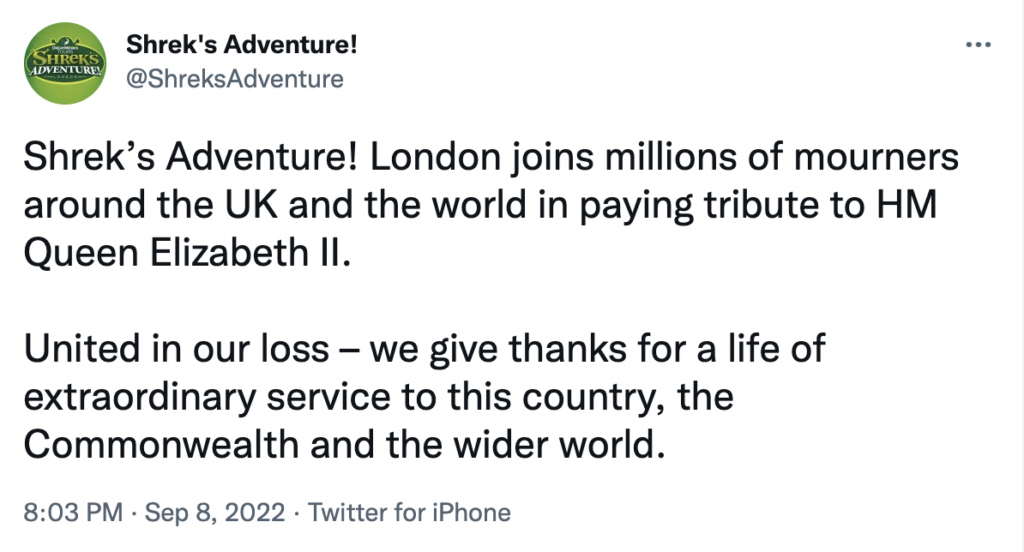

Unfortunately, your undoubtedly sincere efforts to balm the nation’s ailing hearts are met with widespread ridicule and derision. People just don’t seem to think that a jpeg of white text on a black background, extending the thoughts of everyone at Ann Summers or Shrek’s Adventure! London to the Royal Family, are particularly necessary, nor warranted. Some even view the touching tributes as wilfully cynical attempts to marketeer off an elderly woman’s death.

But is the Queen, who lends her image to our literal money, really so sullied by association with commerce? Defenders of the monarchy often argue that the royal family are a great advert for UK tourism. By this logic, when Colonel Sanders and Ronald McDonald extend their branded condolences to the Queen, is it really a marketing ploy, or are they just recognising a fallen comrade? When Jim Henson died, Disney sent a doodle of Mickey Mouse comforting a distraught Kermit the Frog — is what these brands are doing so different?

The Queen is dead and everything is cancelled. The weekend’s football is cancelled. Up-to-date weather reporting is cancelled. NFT sale Bowie on the Blockchain is cancelled. The planned industrial strikes are cancelled. Corwen in Denbighshire’s day commemorating Owain Glyndŵr, who sought to emancipate Wales from the British Crown? Cancelled. Good news, however, if you wanted to go and view the monument to William Wallace — the infamous warrior for Scottish independence, hung, drawn and quartered by (again) the British Crown — in Ayr; that remained open, and lit up in the colours of the Union Jack.

None of these cancellations seemed to be responding to a clamour from the public to do so. There are no baying mobs roaming the streets, patrolling for instances of non-grieving-related activity to snuff out, or Center Parcs holidaymakers sneaking out of their lodges to execute. I get the gnawing suspicion that the cancellations and closures are driven by fear of something else — the possibility of being plastered across the front pages of the right-wing press, under headlines like ‘FOR SHAME: the Village That Street-partied While Queen Lay in State’, or ‘GRATUITOUS: the Local Art Gallery Willing to Exhibit Anything, Except Respect’.It seems healthy that we have to accept that a large section of our news media operates as a national ducking stool, a phantom whose threat disciplines us into modulating our public behaviour and responses, lest we suffer its wrath.

“The first person I speak to is a journalist who has joined The Queue for a feature. After striking up conversation with someone else and discovering that they, too, are a journalist, I begin to grow suspicious that The Queue might be entirely comprised of journalists”

The Queen is dead and I’m trying to find the end of The Queue. The line for the hoi polloi to be able to pay respects to her body at Westminster Hall opened the afternoon before, and already stretches three miles, taking a rumoured nine hours to complete (later, those figures will reach ‘10 hours’ and ‘over 24 hours’ respectively). The phenomenon has gripped the public imagination.

I want to ask those at the back what’s possessing them to join, given the extraordinary length and ensuing discomfort involved. I also suspect the people at the front are sick of being interviewed by now. The mood at the tail end is optimistically cavalier, the way I remember being at the beginning of school trips, before the reality of having to spend 15 hours on a coach with only a DVD of Lee Evans: Live at Wembley to keep us occupied really sank in. Everyone is buoyantly passing around Percy Pigs and clutching Thermos flasks, as yet untroubled by their bladders.

The first person I speak to is a journalist who has joined The Queue for a feature. After striking up conversation with someone else and discovering that they, too, are a journalist, I begin to grow suspicious that The Queue might be entirely comprised of journalists, and the whole thing is an elaborate ouroboros scam to generate commissions. The next dozen or so people aren’t blue-ticked, but provide the same anthropological justifications for being here that I am. They can’t miss this, the downright weird phenomenon of The Queue itself. They saw the coverage and had to be a part of it.

Britons love these Dave Gorman-esque acts of extreme twee endurance: visiting every Wetherspoons in the British Isles, unicycling from Land’s End to John O’Groats, spending a week in a bathtub of baked beans for Comic Relief, queueing for an entire day to be permitted a five-second window to nod at a box allegedly containing the Queen. Why? To simply say you’ve done it, and to be able to recount their observations to their respective audiences later, be they Daily Telegraph readers, group chats, or dinner party guests. The fact that the ends cannot possibly justify the ridiculous means is all part of the allure for middle-class Brits who take perverse pride in it.

Numerous news outlets broadcast continuous, unbroken live footage of The Queue, both as internet streams, and just in place of their television coverage. It takes on an ambient quality, particularly when viewed in the wee hours, surreal and yet completely banal. It seems fitting that The Queue is officially presided over by the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport. We’re watching people ostensibly grieve as a spectacle. We can’t see the Queen. She’s virtually absent from the whole thing.

“Numerous news outlets broadcast continuous, unbroken live footage of The Queue, both as internet streams, and just in place of their television coverage. It takes on an ambient quality, particularly when viewed in the wee hours, surreal and yet completely banal”

The Queen is dead and I am drinking a pint of what tastes like pure line cleaner. A friend has insisted we meet at a Millwall and Rangers pub, which happens to sit near the mouth of The (now 10-miles-and-24-hours-plus-long) Queue. If the ardent royalists are to be found anywhere, surely they will be here. But either they’re all in The Queue, or they’ve also been put off by whatever substance they’re claiming comes out of the beer taps. The pub is mostly dead, save for a gaggle of tourists and a woman in full Royal Navy Officer’s uniform, replete with a couple of medals.

Television screens normally dedicated to the Super Sunday blare out the coverage from inside The Queue. It turns out we’ve arrived just in time to witness the Vigil of the Princes, where various members of the immediate Windsor family “stand guard” around Her Maj’s box. The naval officer spots something and incredulously exclaims, “They’ve put Andrew in uniform?!” She walks directly out of the pub, leaving a half pint.

The Queen is dead and I am at her funeral. I’m standing on a packed stretch of pavement, next to a road her hearse will travel down, transporting her body on its final journey between Westminster Abbey and Windsor Castle, where it will be committed.

We are all here hours before the procession will go past, in order to get a spot. This means we have nothing to do in the interim, save to look eagerly at a completely empty road in anticipation, or else stream the funeral service on our phones. Basically, everyone chooses the latter, Bluetooth headphones in, blinkers on, atmosphere at a minimum.

The first service draws to a close, and they begin marching the Queen’s coffin down the Mall on foot. This takes ages, until they reach a point where they put the coffin in a hearse and it begins making its way towards us. People are fully focused on the empty stretch of road now. One guy keeps an earphone in and another eye on Google Maps, performing a valuable service for the rest of us by keeping us informed of the coffin’s ETA: “15 minutes away now!… 10 minutes!… Only five now!… Two minutes!… Everyone! One minute!…” A sea of smartphones are raised in prepared salute, cameras open and pre-focused. “She’s at the top of the road!” People begin to clap, politely and disjointedly.

Her flotilla drives solemnly past, not slowing down to allow her to lap up the applause, to drink in the adulation. We are permitted the shortest of windows to glimpse her and to bid our farewells. I use mine to get a snap of her hearse. It’s only when reviewing the image that I notice something curious.

There’s nothing in the back of the hearse. Turns out, I’ve actually taken a photo of the car following directly behind the one transporting her body. Now the Queen has driven off, bound for her final resting place, via the M4.

The Queen is dead, and I let the moment pass me by.

Taken from the December/January 2023 issue of Rolling Stone UK. Read the rest of our essays reviewing 2022 here.