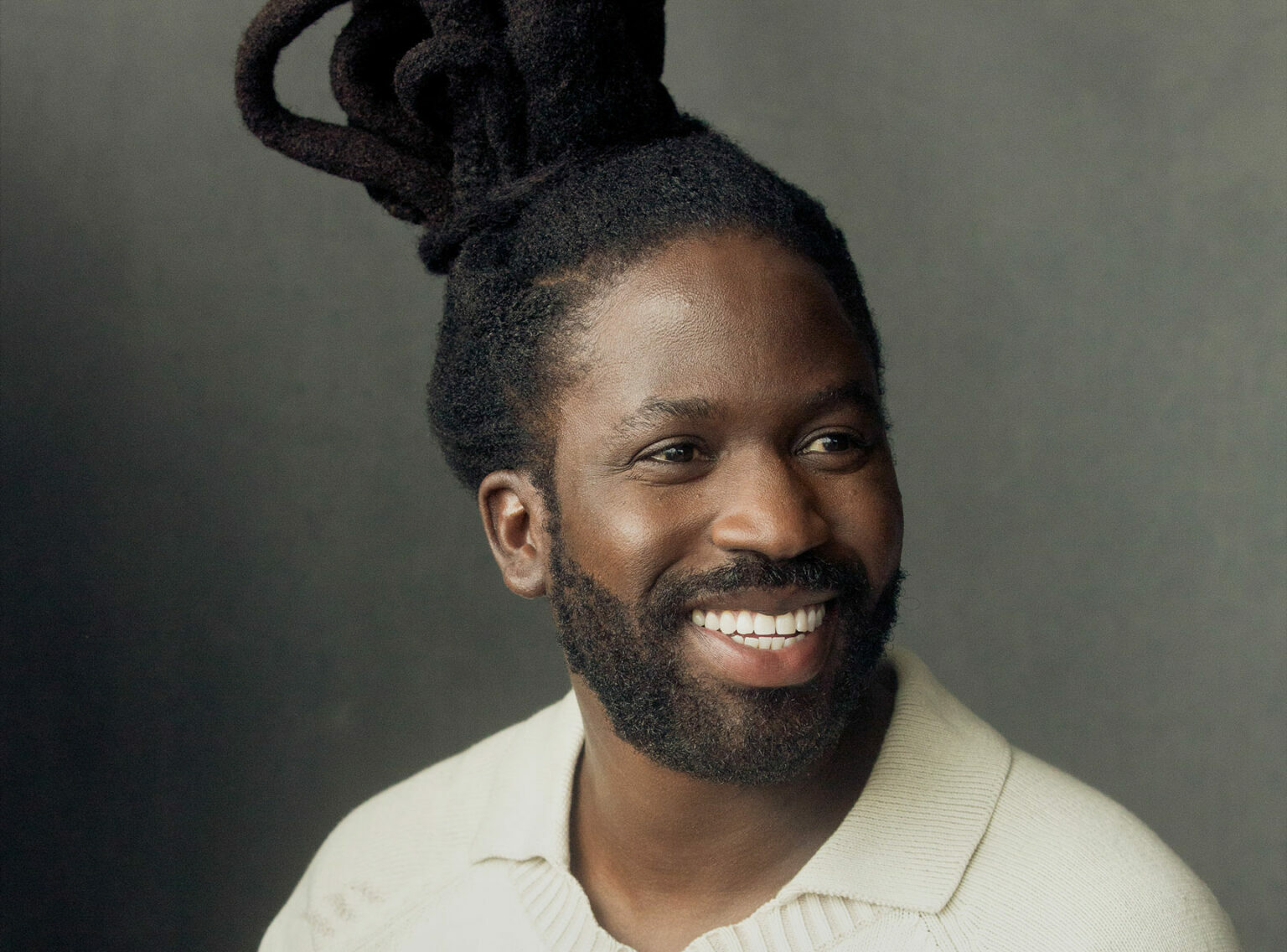

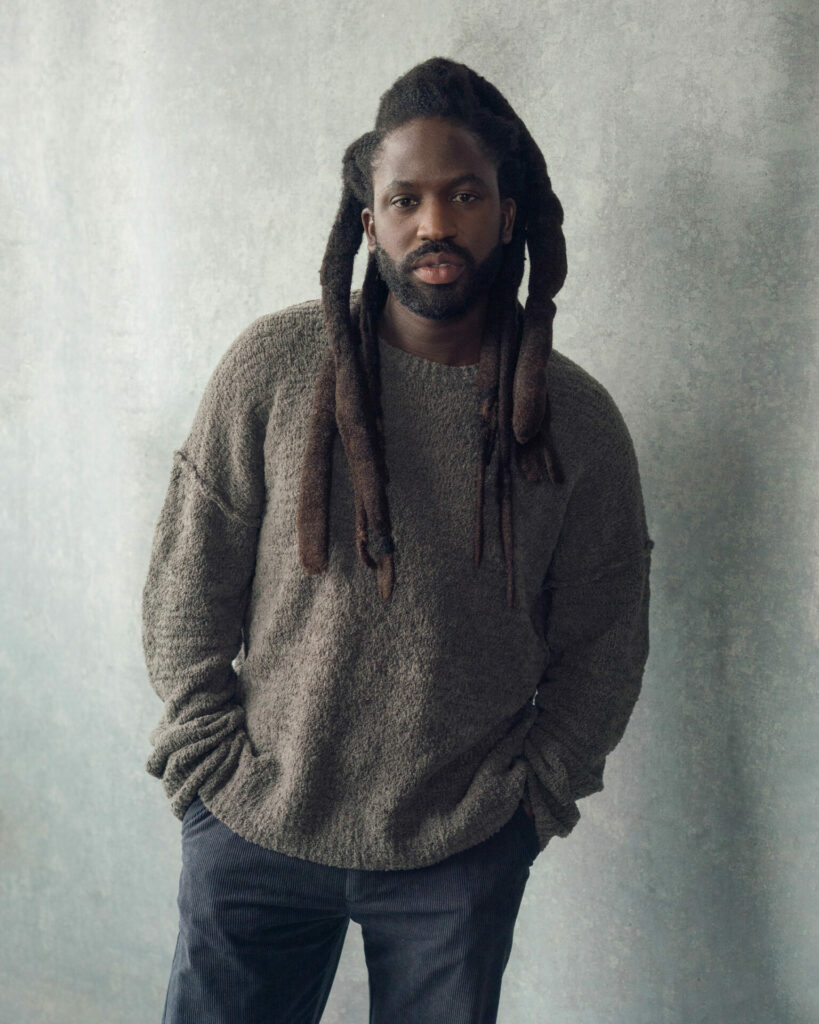

Adjani Salmon tells us about season 2 of ‘Dreaming Whilst Black’

The writer of the BAFTA-winning Dreaming Whilst Black on what viewers can expect from the second series, plus his new sitcom project

The writer of the BAFTA-winning Dreaming Whilst Black on what viewers can expect from the second series, plus his new sitcom project

Humble and deeply knowledgeable, actor and writer Adjani Salmon is a champion of today’s Black filmmakers, whether they’re breaking new ground on YouTube or the BBC. As his BAFTA-winning series Dreaming Whilst Black returns for its second season, he speaks to Rolling Stone UK about how the show is very much rooted in lived experience.

How did you find your way into filmmaking?

When I was 13, my mum bought me a likkle four-megapixel camera for Christmas. My cousin and I, obsessed with kung fu films, shot clips inspired by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon – even playing them backwards so stick fights looked like magic. Man was jumpin’ offa rooftops – all sorts!

Years later, I’d graduated and was working as an architect, but I wasn’t feeling the corporate life. My cousin, studying film in England, came home for the summer. I drove him to sets, and we started making sketches with my uni friends, posting them on Facebook. After he left, Smirnoff Jamaica saw our work and hired us for an ad. That’s when I realised creativity could actually pay. My cousin taught me [video-editing software] Final Cut over Skype in a week, and I never looked back.

How much of Dreaming Whilst Black comes from your own life?

We joke it’s a documentary. Every character is rooted in someone I know. Writing with Ali Hughes, I’d say, “I wouldn’t do that,” and he’d remind me that it’s [my character] Kwabena, not me. From early on, we gave him traits to separate us, so he could be freer, get into funnier situations. We also had a rule: don’t invent racial jokes. Anything in Dreaming Whilst Black really happened – to me or someone else.

The show came from wanting opportunities. The “film school to agent to Spielberg” pipeline wasn’t real. I made a decent short, it hit festivals, but mi nah see no agent there! It’s funny, because that’s basically season one in a sentence: he just wants an agent. I saw Michael Dapaah, Cecile Emeke and Issa Rae blow up online and thought, ‘Let me try that.’ Then I watched Master of None and thought, ‘If an Indian actor in New York can write his life, so can I as a Black filmmaker in London.’

How did things change when the BBC got involved?

We grew as writers. Moving from 10-minute webisodes to half-hours was the hardest shift, but the awkwardness, the silences, are still us. Early notes said our scenes were too short, too internet-paced, so we had to slow down. It’s not lost on me that we had commissioners like Sarah Asante and Tanya Qureshi who understood the cultural nuances. They sharpened us, made sure the jokes landed responsibly and safeguarded the project. The web series was raw; the BBC version is tighter, but still true.

How was the BAFTA experience? Did you feel pressure after the win?

The BBC tells you when they’re submitting you, and I thought, ‘Sick!’ My agent said even a nomination and we’re set, fam. I was just going for the vibes, likkle champagne. When we actually got nominated, I celebrated properly with friends. Seeing my name alongside creators I admired was surreal. But I knew I wasn’t there because I was necessarily the best; I was there because I got the shot. That BAFTA speech was me paying homage to the web series Mandem on the Wall – it could’ve been #Hood Documentary or Ackee and Saltfish, but this time it was us. The pressure wasn’t from the community – that was pure love. Older Black folks would say, “We see you: keep going.” Even Lenny Henry told me he’d seen the work. That felt like being handed a baton. I’ve just got to run with it until it’s time to pass it on.

What can viewers expect from season two?

New types of dreams – fantasy sequences! They can also expect to see Kwabena on the front foot, more assertive and driven than before – risking it all this time.

Is there a moral or message?

We don’t like to think of the show having messages. If people take something from it, great. If they don’t and just enjoy the entertainment, that’s great too. We just want people to enjoy it. I’d much rather the show be open to interpretation. It’s art, not a lecture.

What’s it like juggling multiple roles on season two?

Alongside acting and writing, I’m also the showrunner. When I’m writing, I’m in writer mode. Once pre-production starts, the hats begin to overlap – I’m thinking about logistics, budgets, locations, and sometimes I have to say, “I know we’re shooting this next week, but it needs to change.”

Compartmentalising helps – a skill I learned growing up. As boys, society tells us not to cry, not to show vulnerability. We end up hiding fear, anger – even love. For me, art has always been the outlet. When the web series dropped, even my ex texted, saying, “Is this how you feel?” And she was right. I’d processed so much of my emotions through that work. Art is freedom. Film is my vehicle of expression.

What challenges stand out, and what have been your highlights?

As we say in Jamaica: “New level, new devil.” One was overcoming failure: after pouring two years and all my savings into the web series, nearly a year passed with nothing. Picking myself back up was rough, but my film-school friends held me down. Another [obstacle] came with hyper-visibility after the pilot. Suddenly, it was daily press, becoming guarded, everyone asking, “What’s next?” I had to remind myself why I did this. Ali reminded me: “We made it for the mandem and the galdem, not the press.” A highlight was bringing my mum to the BAFTAs, her seeing the red carpet, the reporters, the stars, knowing she was proud.

What does the future look like for you?

We pray for more TV shows, more films, here and in America. I’m working on a sitcom with BBC Studios called Gabby’s, about a Jamaican family running a Caribbean takeaway. It’s gag-heavy – proper Office vibes. It’s different, and I’m enjoying that.